Despite oppression and discrimination in their day-to-day lives, hundreds of Black men volunteered for service in the Canadian Expeditionary Force between 1914 and 1918, only to be met with another uphill battle simply to go to war.

Most were rejected for service in local fighting units. About 800 eventually ended up in No. 2 Construction Battalion, a segregated support element commanded by mostly white officers. Still others—some 700—managed to join regular infantry units.

Those who made it home returned to a postwar life in Canada similar to the one they left. They were still treated as second-class citizens and, even for those with university degrees, job opportunities were limited.

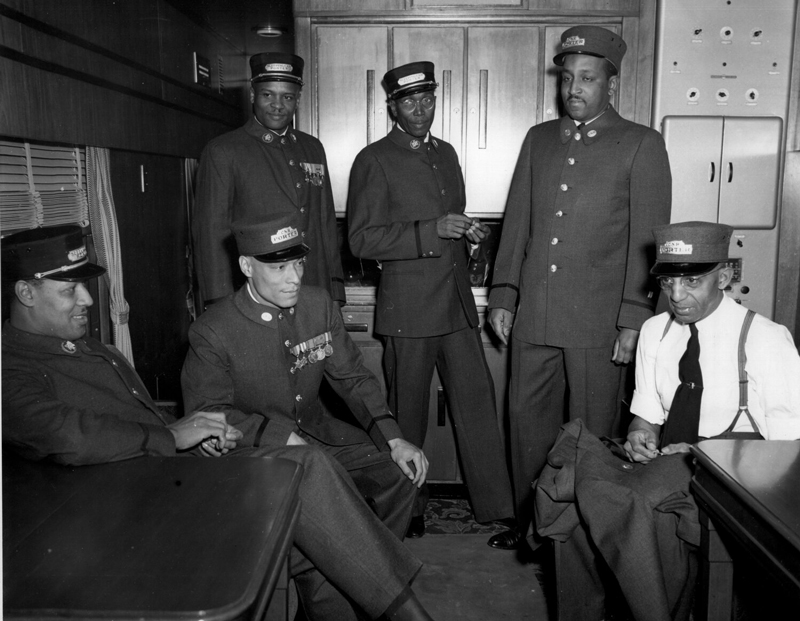

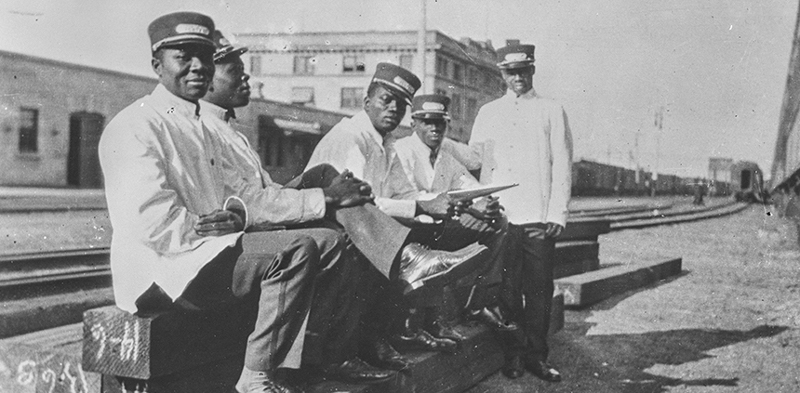

Many were relegated to menial jobs, and one of those carved out for predominantly Black workers—before airlines and the Trans-Canada Highway transformed travel in this vast country—was that of sleeping car porter.

Billed as a “ground-breaking” drama, the eight-episode series will serve as an eye-opener for many Canadians who thought 20th century racism was an American issue.

Centred in the Black community of St. Antoine in Montreal—known at the time as the “Harlem of the North”—the series debuted Feb. 21 on CBC-TV and its streaming service, CBC Gem.

“Why did I get a job as a porter on the railway? I couldn’t get anything else—and I didn’t want to starve.”

Low-paid porters greeted passengers, stowed baggage, prepared berths morning and evening, shined shoes, brushed coats and hats, babysat, cared for the sick and dealt with drunks.

“Why did I get a job as a porter on the railway? I couldn’t get anything else—and I didn’t want to starve,” said union organizer Stanley G. Grizzle.

Quoted in Agnes Calliste’s 1987 Canadian Ethnic Studies paper “Sleeping Car Porters in Canada: An Ethnically Submerged Split Labour Market,” Grizzle described many porters as “intelligent young Black men who had achieved a measure of education that should have guaranteed them a job befitting their academic achievements and in keeping with their training.

“But they were denied those opportunities by a racist society, and instead had to go into a line of work that forced them into that demeaning role of servant.”

Wages were low and raises were rare. Porters had to pay for their uniforms, shoeshine kits and meals. They were also held accountable for missing towels, bed sheets and pillowcases. They relied on tips to supplement their meagre incomes.

A typical shift lasted 72 hours, yet the porters rarely had accommodations of their own.

“When I first started working for the CPR, there was no berth reserved for the porter to sleep in and we spent those precious three hours on a seat in the smoking room,” said Grizzle.

“There was a mattress underneath to put on the seat, with some sheets as well. That was your bed. It was very unhealthy, because men were smoking in there all day.”

It was hard and difficult work. Porters left their families for weeks on end, often travelling across the continent and back on little sleep and with tenuous job security.

This mass firing slowed unionization efforts for more than a decade.

Unions such as the Canadian Brotherhood of Railroad Employees would not allow Blacks as members. In 1917, four porters in Winnipeg organized the Order of Sleeping Car Porters, North America’s first Black labour union.

A Canadian Museum of Human Rights history article said the Black union got no support from its white counterparts, yet still managed to negotiate wage hikes and job protections with Canadian National Railway (CNR) management.

“The union also called out the hypocrisy of white unionists who talked about class solidarity while excluding Black workers,” wrote Travis Tomchuk.

The Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) proved even more resistant to unionization than the CNR, forcing employees to sign contracts that prohibited union activity and firing staff involved in organizing.

In the early 1920s, the CPR dismissed 36 porters, some with as many as 12 years on the job, due to union activities. This mass firing slowed unionization efforts for more than a decade, until porters began organizing behind the U.S.‐based Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP) in 1939.Organizing efforts continued in secret before CPR porters voted to unionize in 1942. A collective bargaining agreement was reached in May 1945. They landed a monthly salary increase, two-weeks’ paid vacation after one-year’s service, overtime pay and better working conditions, including a sleeping berth on each car.

Porters still faced discrimination, however. The senior and better-paid job of sleeping car conductor, for example, was reserved for whites. The BSCP filed a complaint with the federal labour department under the Fair Employment Practices Act of 1953.

After a year of “conciliation and persuasion,” one of the complainants, George V. Garraway, was hired as the country’s first Black conductor.

“These improvements and opportunities were the result of courageous labour organizing in the face of significant workplace and societal racism,” Tomchuk reported.

“Changes in demographics and technology in the coming decades led to less demand for sleeping car porters, but the struggles and experiences of these workers were pivotal for generations of Black Canadians.”

Their stories were never taught in schools and were largely ignored in railway histories.

The CBC series follows train porters Junior Massey and Zeke Garret, brothers-in-arms from No. 2, as they embark on starkly different paths to better lives criss-crossing North America by rail.

The series explores their wartime experiences, including their postwar trauma and trials drawn from actual events.

A CBC spokesperson said The Porter “aims to use the power of TV to address the miseducation of Black Canadian history, specifically how a lot of Canadians aren’t familiar with our own history.”

“The goal is that the impact of the series will be felt long after the credits roll, leaving viewers with a ‘did that really happen?’ reaction that ultimately leads them to unpack the stories among themselves and their communities.”

Black porters worked Canadian railways for decades. Their stories were never taught in schools and were largely ignored in railway histories.

University of Minnesota history professor Saje Mathieu wrote a history of Black porters called North of the Colour Line: Migration and Black Resistance in Canada, 1870 to 1955. He said Black families have not forgotten what they did.

“I was amazed at how often Black families, especially in the West, had recorded their loved ones’ stories, whether they had written them down or actually recorded them on old tapes, many of them I have in my house,” he told CBC.

“So I think that what we’re seeing is finally an awakening by archives, by bigger platforms to the pearls that these stories represent.”

Said Grizzle: “We did not bow down to the racism and the segregation imposed on us. We stood up for our rights.”

—

The Porter airs on CBC at 9 p.m. EST on Mondays. Visit here for more.

Advertisement