Spirit squad

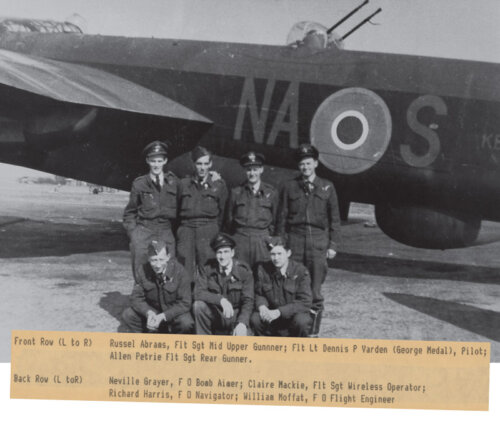

Solving the mystery of how a seemingly random bomber crew photo ended up in the archives of a small-town Ontario school library.

Solving the mystery of how a seemingly random bomber crew photo ended up in the archives of a small-town Ontario school library.

How the British and their Canadien subjects turned back the 1775-76 attack on the Province of Quebec.

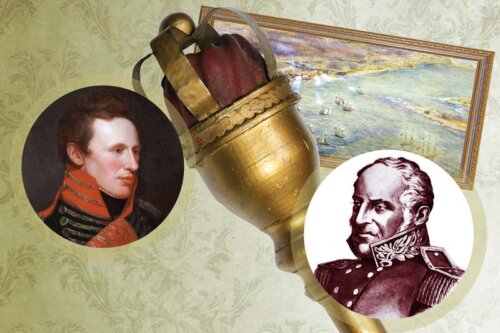

An American 1812 war prize, the return of the Mace of Upper Canada to Ontario symbolized the evolution of cross-border relations

As Operation Veritable’s launch approached, the two opposing generals braced for a fight

Get the latest stories on military history, veterans issues and Canadian Armed Forces delivered to your inbox. PLUS receive ReaderPerks discounts!

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Free e-book

An informative primer on Canada’s crucial role in the Normandy landing, June 6, 1944.