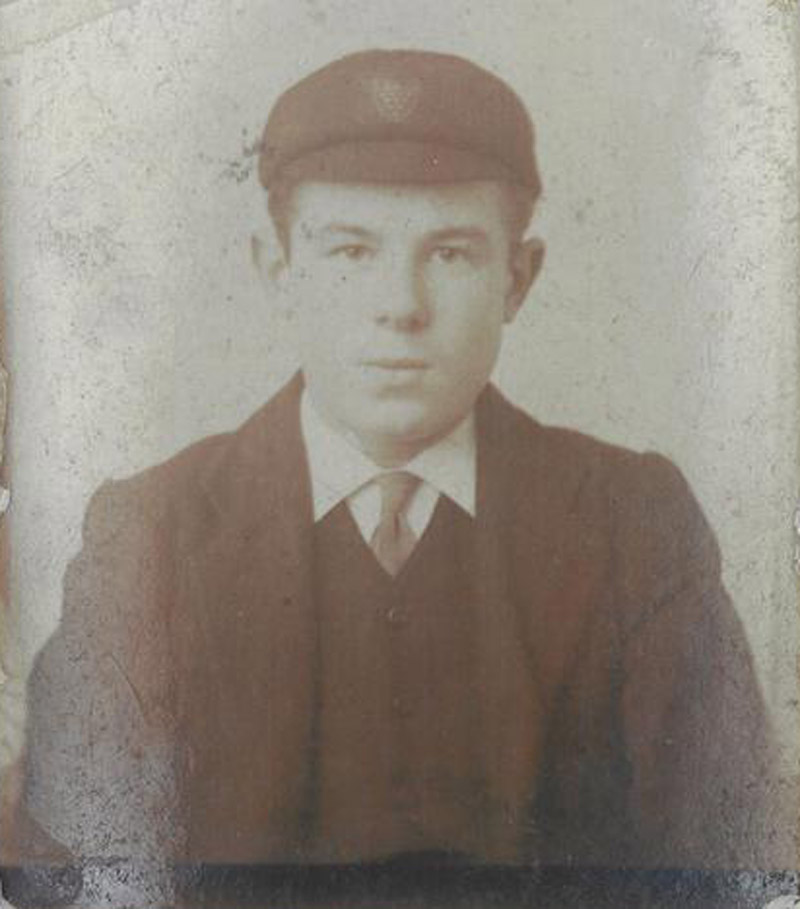

Clifford Robinson Oulton was 14 years old when he joined the 145th Battalion (New Brunswick) of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. [Albert County, N.B., Museum]

Oulton was technically still a child who, by the looks of him, wasn’t yet shaving.

His father George, a railroad pipefitter, had died. He’d lost a brother in 1909. His mother Dora and four sisters lived just outside of town, in Bridgedale. Times were tough, no doubt.

Oulton’s army medical history demanded to know “when vaccinated last.” The doctor who conducted his physical examination, a major, wrote “when a child.”

Weighing 120 pounds and standing five-foot-four-and-a-half-inches tall, Oulton was technically still a child who, by the looks of him, wasn’t yet shaving. He listed his occupation as “farmer” and his birthdate as Dec. 2, 1899. That would have made him 16. His papers, however, listed his “apparent age” as 18 years, one month.

As it turned out, Clifford Robinson Oulton would never see 18—or even 16, for that matter.

Those who were too young and too old enlisted to fight in the First World War.

Canadian service was supposed to be restricted to males between the ages of 18 and 45. But in a time when birth certificates were not readily available, those considered too old to fight blackened their hair with shoe polish and those too young feigned confidence and experience, forged documents, and sometimes brought letters, friends and even family to vouch for them.

Between 15,000 and 20,000 underage soldiers enlisted in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The British Army took in nearly 250,000. Some 2,000 Canadian youth (under 18) were killed.

Why the rush to sign up? The first units to head overseas from Canada were 70 per cent British-born. By war’s end, the balance had shifted to 51 per cent born in Canada. Still, many of those were the sons of British-born immigrants—and Canada was still a dominion of the British Empire.

As a result, many an enthusiastic volunteer was motivated by loyalty to king and country—the old country. Others saw opportunity and/or adventure on faraway shores. Even the prospect of three square meals a day was irresistible to some.

A recruitment campaign for the 198th Overseas Battalion (Canadians Buffs) outside of Toronto City Hall in 1916. [LAC/PA-072627]

“With 260 infantry battalions raised across the country, many of these new units competed against each other for recruits in the larger cities,” says the Canadian Encyclopedia. “Often, the units turned a blind eye to those who did not meet age requirements.

“With no national list of recruits who had been denied service, enterprising youth or greybeards could try to enlist time and time again or with different units. Most found a way into the service.”

The average age of a Canadian soldier was 26, even younger in the infantry battalions at the front. Just 20 per cent were married with children.

Ironically, the last-surviving Canadian veteran of the First World War was also among the youngest to sign up.

Impressed by the salary of $1.10 a day—more than double the going labour rate—and two recruiting officers who quoted the poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade,” John Babcock of Frontenac County, Ont., enlisted at 15.

John Babcock was only 15 years old when he joined the 146th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. [Wikimedia]

When 50 recruits were summoned for the Royal Canadian Regiment, Babcock volunteered, claiming to be 18. Officials soon discovered he was only 16 and placed him in a reserve unit known as the Boys (or Young Soldiers) Battalion in August 1917.

He never made it to the front; he was training in Britain when the war ended.

Lance-Corporal Babcock died on Feb. 18, 2010. He was 109.

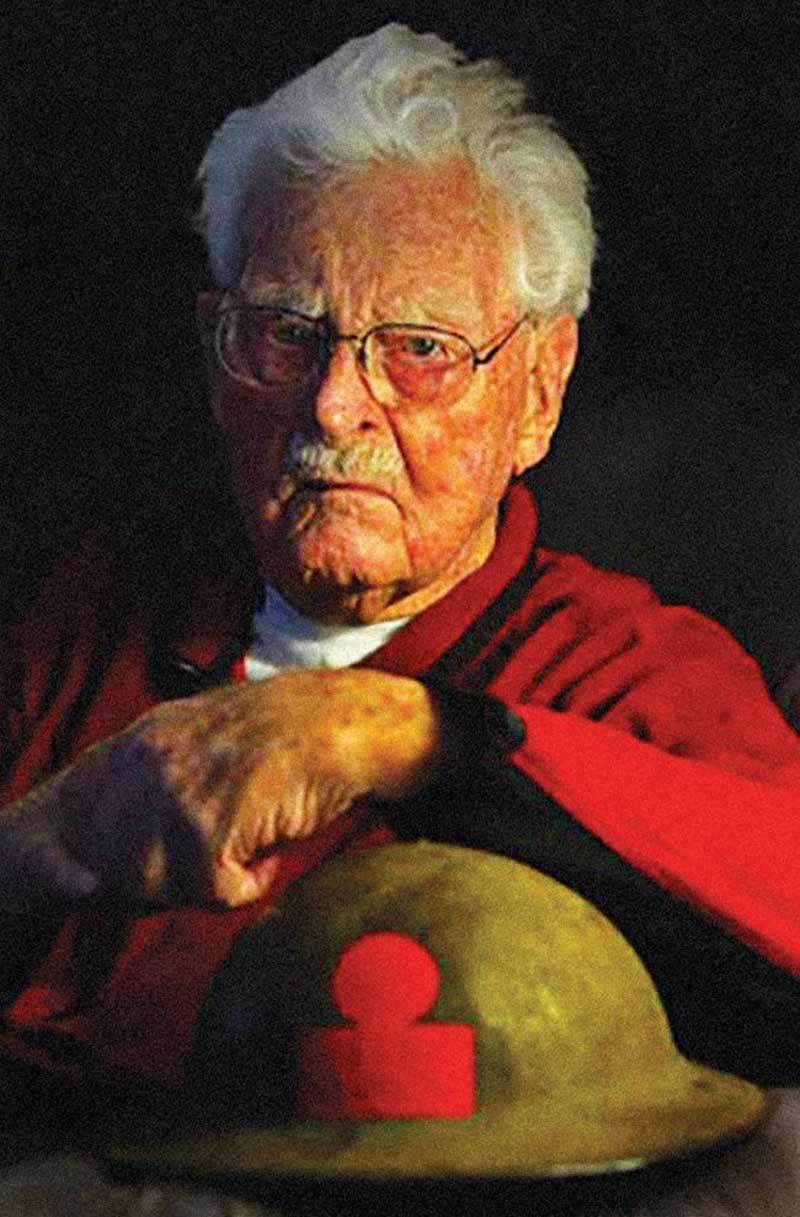

John Babcock was the last-surviving Canadian veteran of the First World War. He died at the age of 109. [Gerontology.Wikia.org]

By contrast, Oulton’s service, like his life, was short and extremely eventful.

He arrived in England aboard SS Tuscania on Oct. 7, 1916, and the army wasted no time in getting him where he apparently wanted to go. By Nov. 3, he was at the front for the last days of the Battle of the Somme with the 5th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles.

He saw more intense action with 5CMR the following spring, tasting victory at the seminal Battle of Vimy Ridge and on Hill 70 four months later, in August 1917.

He told them he was 43 and nobody, apparently, batted an eye.

In October, he joined in the epic fighting at Passchendaele, where his battalion was dealt 60 per cent casualties in a single day. Oulton caught multiple bullet wounds, probably from a machine gun, on Halloween morning and died in No. 44 Casualty Clearing Station near Rouen the next day. He was 15 years, 334 days old.

Canadians carry a wounded soldier on a stretcher during the Battle of Passchendaele. [LAC/PA-002140]

It’s been said that old men—politicians and generals—send the young to die in wars. But those officially considered too old to fight also found a way into the war to end all wars, although events didn’t always work out as anticipated.

House painter William Elmyr Van Every was 52 when he walked into a Toronto recruiting office on Nov. 22, 1915. He told them he was 43 and nobody, apparently, batted an eye.

He was one of six Brant County, Ont., Van Everys to sign up. His brother Maurice—a merchant and no spring chicken himself at 45—had told recruiters he was 39 when he enlisted three days before William. A private in the 116th Battalion (Ontario County), he was killed at Arras on Sept. 17, 1917.

The elder Van Every never made it overseas. William died of a cerebral hemorrhage on April 10, 1916, while in training with the 123rd Battalion (Royal Grenadiers) at Toronto’s Exhibition Park. The site had become Exhibition Camp at the war’s outset in 1914.

In Britain, the minimum age for recruitment was 19, but 14-year-olds and other young teenagers were even more common in the ranks of the British Army than the CEF.

“It was obvious they weren’t 19,” said historian Richard Van Emden, “but you’d have a queue of men going down the road, you’re getting a bounty for every one who joins up—are you really going to argue the toss with a young lad who’s enthusiastic, who’s keen as mustard to go, who looks maybe pretty fit, pretty well?

“Let’s take him.”

The youngest British soldier of the First World War was verified in 2013 to have been Sidney Lewis, who enlisted at age 12. He fought at the Somme at 13. When his frantic mother learned of his whereabouts from a comrade home on leave, she brought his birth certificate to authorities and demanded he be released.

Despite his deception, Lewis was awarded the Victory Medal and the British War Medal. He re-enlisted in 1918 and served with occupation forces in Austria. He became a policeman in Kingston upon Thames after leaving the army and served in bomb disposal during the Second World War. He then ran a pub in East Sussex and died in 1969.

Even if they survived the maelstrom, the enthusiasm of young and old alike would inevitably evaporate once they were confronted by the realities of what they’d signed up for.

“He had turned up at the recruiting station in his short trousers.”

Fifteen-year-old Cyril Jose, an adventure-seeking tin miner’s son from the hard-pressed region of Cornwall, England, was set on joining up in 1914.

Cyril Jose joined the 2nd Battalion, Devonshire Regiment at the age of 15. [IWM]

“He was way too young,” she said. “He used to tell us how he had turned up at the recruiting station in his short trousers, his school uniform, and was told to go away. “But he just went around the corner, came back and said he was 18 and they let him in.”

Described as a mischievous boy, Jose was brimming with confidence when he wrote his sister from training camp before he was sent to France.

“Dearest Ivy, stand back,” he wrote. “I’ve got my own rifle and bayonet. The bayonet’s about 2ft long from hilt to end of point. Must feel a bit rummy to run into one of them in a charge. Not ’arf.

“Goodbye and God bless you, from your fit brother, Cyril.”

Fighting with the 2nd Battalion, Devonshire Regiment, Jose was wounded at the Somme in 1916, surviving bullets to the chest and the left arm. His letters soon lost their spark.“It seemed I was alone in a field of dead men,” he wrote from hospital. “They were all the result of the few minutes going across.

“Out of our battalion, 27 answered roll call after the battle. Twenty-seven out of about 900 or 1,000 men. Men went down like corn before a scythe.”

He described how they were moved to the front the night before and scoffed at his commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Archibald Sutherland, and his “pompous platitudes.”

The colonel, he said, suggested there would be “little resistance.” As soon as he went over the top, Jose said he knew “at that distance we had no possible chance of surprising them.”

Somewhere along the way, someone discovered Jose’s true age.

“You know what a hailstorm is? Well, that’s about the chance one stood of dodging the bullets, shrapnel.”

He was shot within five minutes: “They simply cut us down with their rifle and machine gun fire.”

British troops advance through barbed wire into no man’s land at the Somme. [Chronicle/Alamy/DR9E30]

The teenager, by now old beyond his years, made it home, married, worked as a postman, and had two daughters.

He remained bitterly anti-war for the rest of his days. In one letter, he heaped scorn upon the British commander, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, later dubbed “The Butcher of the Somme.”

“What brains Earl Douglas must have,” he wrote. “Made me laugh when I read his dispatch. ‘I attacked.’ Old women in England picturing Sir Doug in front of the British waves brandishing his sword at Johnny in the trenches…attack Johnny from 100 miles back. I’ll get a job like that in the next war.”

Cyril Jose died in 1984, leaving four grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren. He was 84 years old.

Advertisement