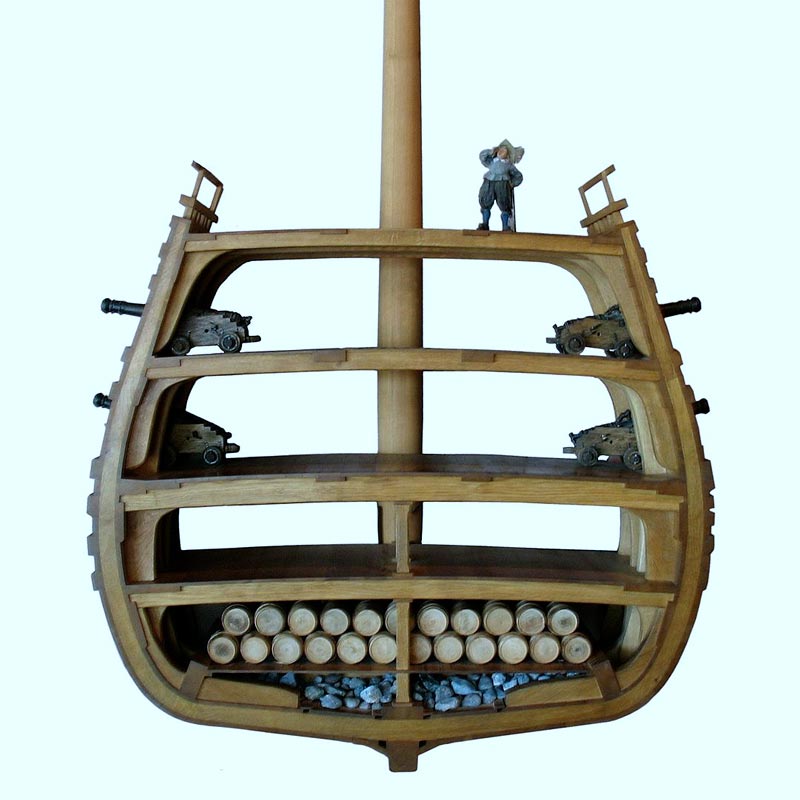

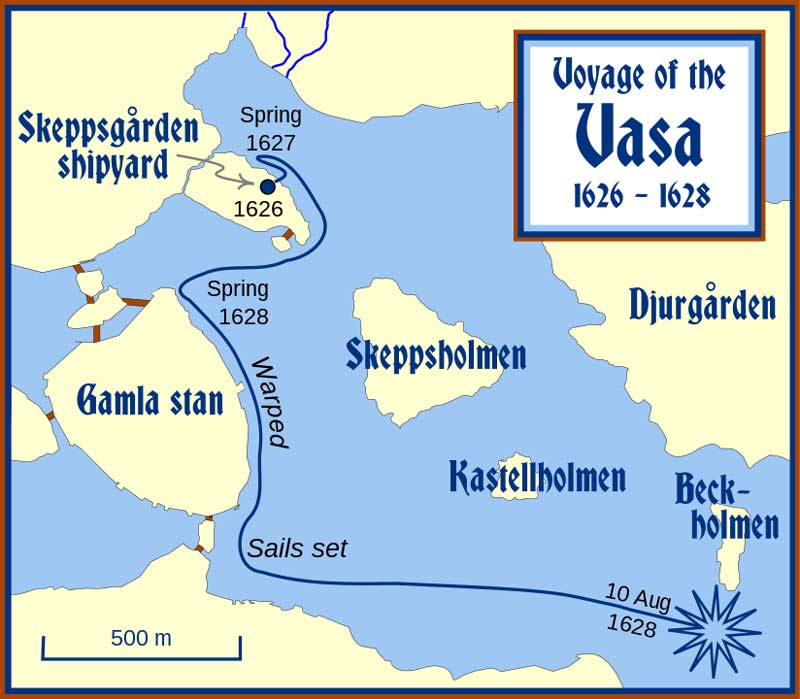

But Vasa, top-heavy with lavish decor—much of it celebrating the king’s family history—and 64 bronze guns, twice as many as its original design called for, barely sailed a kilometre when a wind gust toppled the 69-metre vessel on Aug. 10, 1628.

Water flooded its gunports, which had been opened to fire a salute as the ship set out on its maiden voyage. It was unable to right itself.

The vessel foundered and, 20 minutes after casting its lines, Vasa was at the bottom of Stockholm harbour. Thirty of the 150 aboard were dead and onlookers crowding the docks and swarming in boats off the Swedish capital were horrified.

For 333 years, the ship lay upright in 32 metres of water just 120 metres offshore, its wood preserved by the cold, salty, oxygen-poor Baltic waters. The wreck, still largely intact, was raised in 1961 and ultimately stored in a climate-controlled museum after years of painstaking preservation efforts.

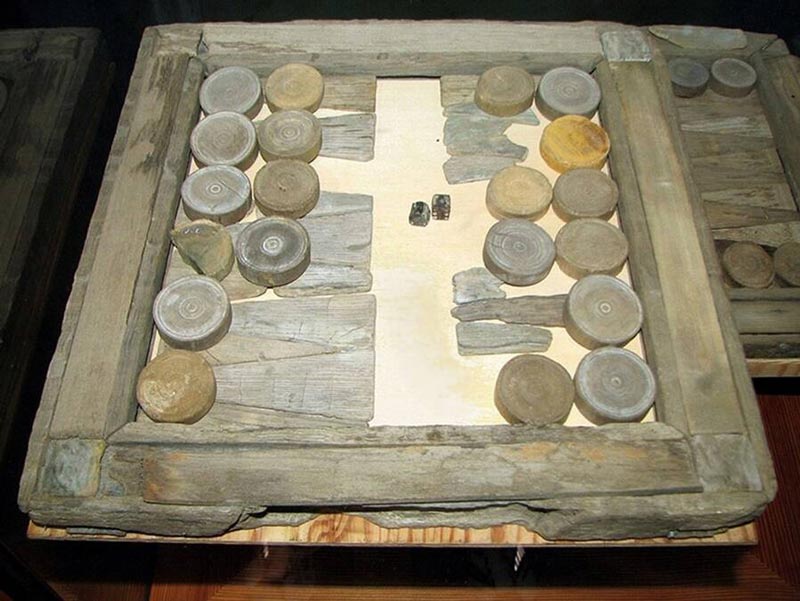

The hulk yielded a wealth of artifacts—40,000 objects found in and around it, including clothing, weapons, cannons, tools, coins, cutlery, food, drink and six of its 10 sails.

But with new technology at hand, researchers at the Vasa Museum in Stockholm received permission to exhume the bones for further study. Working with genetics experts at Sweden’s Uppsala University, they used mitochondrial DNA testing to identify ages, heights and medical histories of the dead crew.

They determined what they had found were 15 “well-defined adults” and at least two others, including a child under the age of 10. Confirming gender was more complicated. Mitochondrial DNA cannot reveal the sex of individuals.

Based on early bone analysis, scientists had assumed all but two of the dead, who were wearing women’s clothes, were male. Researchers were so sure of their findings they had even given the remains clinically known as “G” the name Gustav.

Still, others had their suspicions.

“It is very difficult to extract DNA from bones that have been on the seabed for 333 years, but not impossible,” Marie Allen, professor of forensic genetics at Uppsala University, said in a statement.

“Simply put, we found no Y chromosomes in G’s genome. But we couldn’t be completely sure and we wanted to have the results confirmed.”

After sequencing G’s DNA using four different methods, the lab determined “he” was actually a “she.”

Allen appealed to Kimberly Andreaggi, a former student now working at the U.S. Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory. The lab uses more precise nuclear DNA testing to identify soldiers killed during and since the Second World War. It has also sequenced DNA from Czar Nicholas II of Russia, who was executed by Communists in 1918, and from crew of the Civil War ironclad U.S.S. Monitor.

In 2016, the lab developed a “next-generation sequencing method” that could capture and enrich damaged or compromised human DNA.

While G’s sample was damaged, researchers told the New York Times it was better preserved than remains the lab normally examines. After sequencing G’s DNA using four different methods, the lab determined “he” was actually a “she.”

The scientists struggled to get G’s full genetic makeup, in part because her bone structure was androgynous. Her facial bones looked “a little bit more male than female,” said museum director Fred Hocker, and her spine appeared to have “lived a life of very hard work.”

The Swedish navy allowed sailors’ wives to live on warships as long as the ship remained in home waters. G was found next to a male skeleton, along with the two other female skeletons.

“In the tragic moment of sinking, it’s not hard to imagine that husbands and wives found each other,” said Hocker, adding there also remains the possibility that G passed as a man aboard ship.

The museum is studying the clothing fragments found around G’s remains in an attempt to answer that very question. Meanwhile, it has commissioned a new female reconstruction of G to display next to the original male version.

And it is considering whether to rename Gustav to Gertrud, a common G-name for women in Sweden in the 1620s, or to simply stick to using letters to identify the skeletons, which are typically assigned in the order of their recovery.

Similar genetic testing is being carried out on 14 other remains. Hocker said additional DNA testing will eventually provide intimate details about the recovered remains of Vasa’s crew, down to whether they had freckles or wet or dry earwax.

The ship was richly decorated as a symbol of the king’s ambitions for Sweden and himself.

Through what is known as its “age of greatness” or “great power period,” Sweden transformed itself from a sparsely populated, poor and peripheral northern European kingdom of little influence to one of the major powers in continental politics during the 17th century.

Between 1611 and 1718 it was the dominant power in the Baltic, eventually gaining territory that encompassed all sides of the sea. In 1625, however, 10 Swedish warships ran aground on a patrol in the Bay of Riga, contributing to the pressure that was on already on Vasa’s production.

The ship was richly decorated as a symbol of the king’s ambitions for Sweden and himself. King Gustav, who led his armies in Poland throughout much of the ship’s construction, nevertheless kept methodical tabs on the entire project, at one point changing the specifications and ordering a second gundeck.

The king was impatient to see it take up its station as flagship of the reserve squadron at Älvsnabben in the Stockholm Archipelago. Construction was accelerated and Vasa was rushed through sea trials.

No one was punished after an inquiry, but reasons for the disaster appeared obvious to later generations: time pressures; shifting specifications, the effects of which were compounded by a lack of documentation; over-engineering and -innovation along with a lack of scientific methods and reasoning.

The management world has a name for human problems of communication and management that cause projects to founder and fail: “Vasa syndrome.” The sinking remains a fundamental case study in business.

“An organization’s goals must be appropriately matched to its capabilities,” said the 2001 Academy of Management paper Vasa Syndrome: Insights from a 17th-Century New-Product Disaster.

In Vasa’s case, “there was an over-emphasis on the ship’s elegance and firepower and reduced importance on its seaworthiness and stability, which are more critical issues.”

The aftermath of the January 1986 space shuttle Challenger disaster produced a primary example of Vasa syndrome at work. The academy paper notes that in developing the Hubble Space Telescope, NASA repeated many of the same mistakes that led to the Challenger explosion, due largely to the fact the lessons of the tragedy were not stored in the organizational memory.

According to the museum, Vasa is the only preserved 17th-century ship in the world and continues to yield revelations about the era from which it came and the people who lived in it.

“We want to come as close to these people as we can,” said museum historian Anna Maria Forssberg. “We have known that there were women on board Vasa when it sank, and now we have received confirmation that they are among the remains.

“I am currently researching the wives of seamen, so for me this is especially exciting, since they are often forgotten even though they played an important role for the navy.”

In October 2022, maritime archeologists announced they had discovered Vasa’s sister ship, Applet, launched by the same shipbuilder in 1629. Applet was declared unseaworthy after the Thirty Years’ War and scuttled off the island of Vaxholm in 1659 to form part of an underwater barrier for enemies accessing Stockholm by sea.

Advertisement