Tufts Cove is a shallow, innocuous little inlet nestled at the back end of Halifax Harbour on the Dartmouth side between a power station and the abandoned military neighbourhood of Shannon Park.

Because of its proximity to the 56-year-old generating plant and what was once housing for Cold War-era sailors and their families, the cove is fenced off, blocking access to both the water and land. No one ever goes there, anyway; they have no reason to.

Water access is too shallow for much more than a rowboat and the cove itself is little more than four metres deep at its deepest point during high tide. And for decades before a nearby treatment plant was built, the cove was filled with raw sewage.

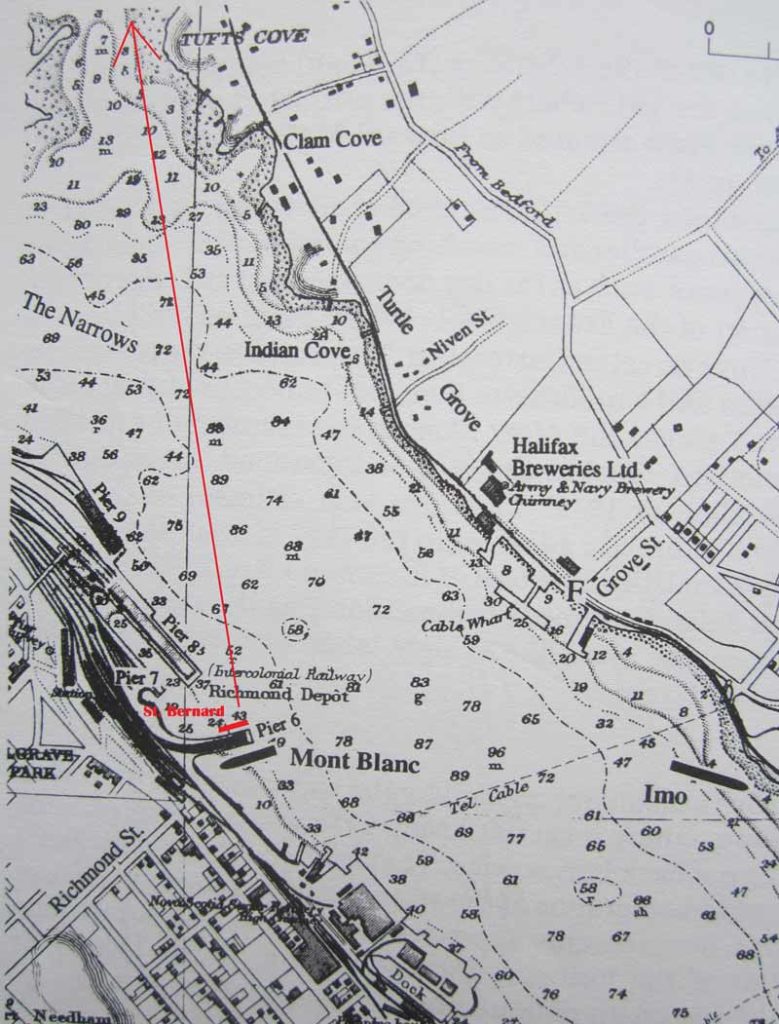

Diver Robert (Bob) Chaulk wasn’t even thinking about the cove’s proximity to the Dec. 6, 1917, Halifax Explosion when he decided this spring to finally take a look at the unexplored body of water. It lies half a kilometre southeast of Bedford Basin and The Narrows where two ships, SS Imo and SS Mont-Blanc, collided more than a century ago.

“For many years, I couldn’t get to sleep the night before a dive, I was so excited.”

Chaulk, who’s written five books since he retired from his job as project manager for a software company, set out thinking he might find something to add to his extensive bottle collection.

The transplanted Newfoundlander has gathered hundreds of glass and stoneware bottles over 34 years of diving, much of it in Halifax Harbour and adjacent Bedford Basin, where half of Duc d’Anville’s ill-fated 18th-century invasion fleet lies buried, transatlantic convoys formed up during two world wars, and cargo ships dumped storm-damaged Volvos over the latter half of the 20th century.

“For many years, I couldn’t get to sleep the night before a dive, I was so excited,” Chaulk said in an interview with Legion Magazine. “When I go in the water, as soon as I start to go down, this feeling of well-being just comes over me.

“I’m so comfortable in the water and so glad to be there but, at the same time, I have to remember that the sea is not my friend and it’s going to harm me if it gets a chance.”

Tufts Cove didn’t pose much of a challenge, though the rocky entrance was so shallow he tipped the motor on his 17-foot, home-built boat up out of the water to ensure he got in. Among the deepest in the world, the harbour itself averages 18 metres at low tide and the Basin, at its deepest, is 71 metres to the bottom.

Chaulk first tried diving the cove several years ago, but the water was so silty he gave up and didn’t go back until this May when a lack of fresh dive sites prompted him to give it another try. Early spring offered the best opportunity for clear water.

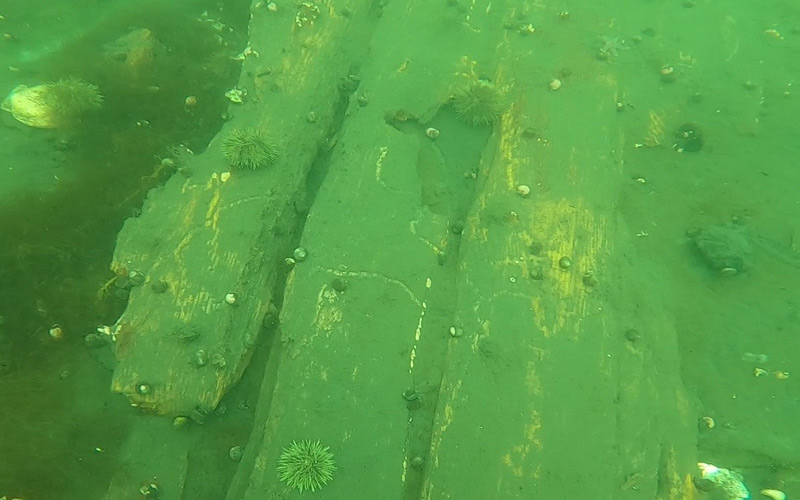

Over the side he went, the water deepening as he swam and scanned the bottom. He found a surprisingly hard bottom, relatively silt-free. There were manmade objects all around him—broken dishes and bottles, including a century-old keeper: a clear-glass bottle embossed with the words “White Eagle Bottling Co. W. Everett Mass.,” which he stuffed in his bag.

He came across some big wooden planks. He assumed they were part of a wharf.

“I was poking around there because there were a few bottles,” he said. “And then I discovered that it was a long piece of wood, like 20 feet long.

He concluded it had to be wreckage, possibly from the 1917 Mont-Blanc explosion that killed about 2,000 people.

“It kinda got my attention because I saw an iron spike driven in it, but driven through the edge. So I looked down and I realized that this plank was probably three inches thick. Well, that’s wider than a plank you would buy.”

It had to be old. On closer inspection, he found that the spike went through the plank’s 13-inch width and into the one next to it. “I thought, ‘geez, that looks like wreckage from a wooden ship.’”

At that, he went home and spent a good part of his night in bed wondering what he had found. He concluded it had to be wreckage, possibly from the 1917 Mont-Blanc explosion that killed about 2,000 people.

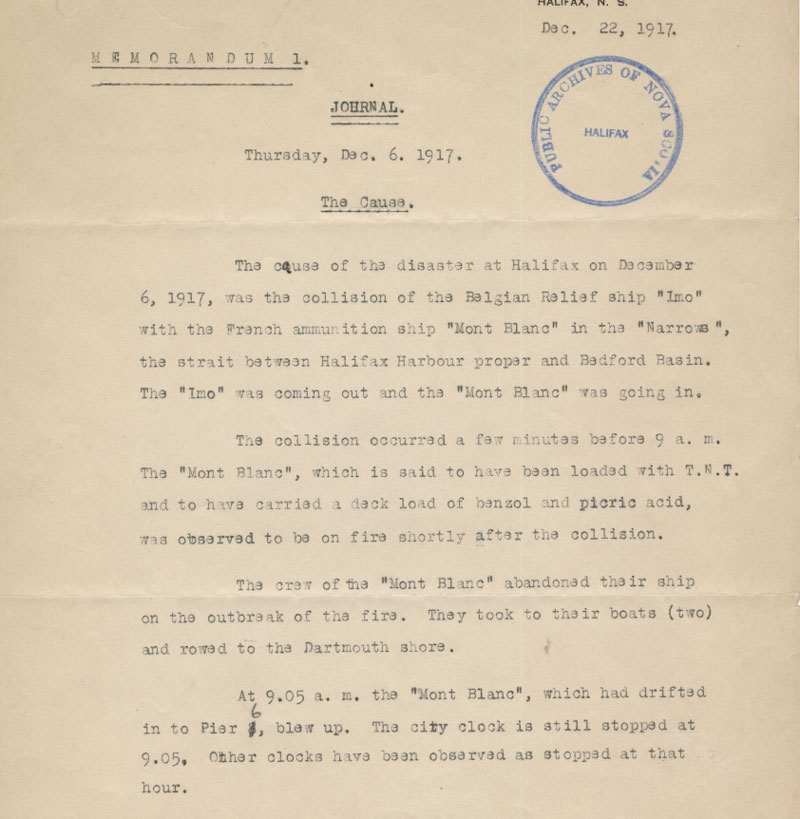

The French munitions carrier caught fire after colliding with the Belgian relief ship Imo at the entrance to The Narrows. It drifted into Pier 6, at the northern end of what is now the Halifax Shipyard, where it burned until it blew up 20 minutes after the collision.

Among the dead were three crewmen of the three-masted lumber schooner St. Bernard, which was docked at Pier 6 when Mont-Blanc exploded. The wooden vessel, built in Parrsboro, N.S., and recently purchased by a company registered in British Guiana, disappeared with barely a trace. At 27.6 metres and 123 short tons, it was smaller than the two-masted Bluenose (63.6 metres; 284 short tons).

Mont-Blanc’s hefty anchor shaft, weighing more than half a tonne, flew across the city and landed more than four kilometres away, at the head of the Northwest Arm beyond the peninsula’s western edge, where it still sits today.

Chaulk returned to the cove, directly across the harbour from what would have been Pier 6. The pier was located near the spot where today Arctic patrol vessels are being built for the Royal Canadian Navy. He measured everything and, when he was done, he decided to do a little more exploring until his air tank ran dry.

“I poked around a little bit and I came upon this anchor. And I thought, ‘holy smokes, look at that!’ It was a good-sized anchor, about six feet long. It was a classic…with the two claws, the big ring in it, and so on.

“I thought, ‘that is a reasonably old anchor; I betcha that’s connected to that wreckage.’”

He studied the anchor, its specific location, its orientation and other evidence. He concluded the piece, with corrosion and growth encrusting about a metre of chain, its shank and metre-wide flukes, was not attached to anything.

“It just appeared here. It fell overboard, fell off a wreck, but it was not anchoring a ship. An anchor is designed to lie a certain way and so on, and it was not doing any of that.”

He returned the following day and investigated the cove some more. He confirmed that no ship could have entered over the shallow glacial rocks that effectively block the entrance. He found more wreckage, including corroded iron and a rotting “knee,” a piece of wooden bracing used in wooden ship construction.

The wreckage, he noted, was spread around randomly, not concentrated in one spot as one would expect of a vessel that sank in a shallow, sheltered, current-free cove.

“The schooner’s crew were last seen desperately trying to untie their lines and get away from the wharf.”

“I had finally satisfied myself that there was never enough water for a ship with an anchor that big to float in there, even if it was pushed in there as a hulk,” or derelict for disposal, Chaulk explained. “So where did it come from?”

One option is the unlikely possibility that a half-dozen men carried the 136-kilogram anchor, placed it in a rowboat, transported it to Tufts Cove, and dumped it. The alternative explanation is far more likely—and intriguing.

“The other option is, it had to come in by air…. And the only way I can think of that it came in by air was with the help of the Halifax Explosion.”

He went off to research the disaster and discovered the story of St. Bernard and the fact that it was only metres away when Mont-Blanc ran aground on the harbour’s Halifax side and blew. The crew of the munitions carrier had abandoned ship and sought shelter in woods on the opposite shore. All but one survived.

“The schooner’s crew were last seen desperately trying to untie their lines and get away from the wharf,” says an account in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic.

St. Bernard “got nailed and disappeared,” said Chaulk. “There was nothing of it ever found” aside from some pieces of her keel recovered amid what was left of Pier 6.

“If you stand up at that point and…you draw a straight line from where the St. Bernard would have been,” Chaulk said, “it puts you right in Tufts Cove.”

“Both the wood and the anchor I found are of the dimension that a vessel such as the St. Bernard would have used,” Chaulk wrote. “The presence of the anchor and the other bits of iron and scraps of wood makes it appear that they are all related.

“The St. Bernard would have been tied to Pier 6 with the bow facing outward. The force of the explosion would have taken the bow as a unit, complete with decking, anchor(s), windlass and other pieces of the schooner and sent it into the air, spreading it across The Narrows and beyond.”

Roger Marsters, curator of marine history with the Nova Scotia Museum collections unit, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, has known Chaulk for years and expresses great confidence in his work.

“While he himself notes that the evidence to date is circumstantial, his reasoning is elegant and sound,” Marsters said in an email interview. “I am certainly intrigued; the fate of St. Bernard’s remains is a question we’ve been considering at the museum for many years.

“Given its proximity to the blast, this part of the city is peppered with remains of the Explosion. Even now, more than a hundred years later, pretty much every year people bring us new metal fragments for identification from districts adjacent to the blast. While it’s impossible to be certain without additional evidence, it is entirely plausible that the artifacts Bob has located resulted from the Explosion.”

Historically significant shipwrecks are protected by Nova Scotia’s Special Places Protection Act, he noted.

“The museum’s preference is to leave items such as these in place for potential future study. By working with members of the diving community such as Bob, we can learn more about the region’s maritime past by studying these features in situ, in their original contexts, than by returning them to the surface.”

Advertisement