They called him “Raffy.” He was one of some 1,800 Canadians and about 100 Newfoundlanders who enlisted directly in the Royal Air Force before the Second World War or in the first year of the conflict. At least 1,100 were aircrew, outnumbering their Royal Canadian Air Force counterparts at the beginning of the war. Many were engaged in the earliest combat sorties and went on to particularly outstanding careers. Among them was Gordon Learmouth (Raffy) Raphael.

Raphael was born in Brantford, Ont., on Aug. 25, 1915, and educated in Quebec City, before going to England in 1934 to attend the Chelsea College of Aeronautical and Automobile Engineering.

“I wanted to design aeroplanes,” he said, “but after a year I discovered that what I really wanted to do was to fly. So I took a short service commission in the RAF in 1935.”

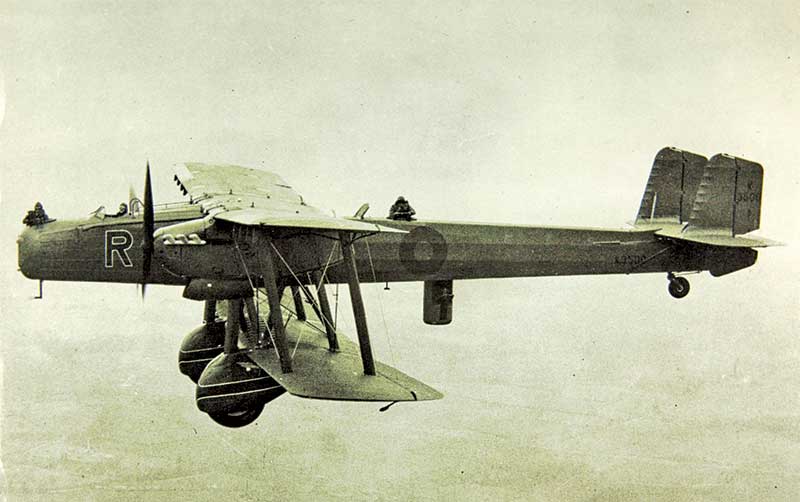

He was appointed an acting pilot officer on probation on Jan. 20, 1936. In August, he was posted to No. 7 Squadron, flying Handley Page Heyfords out of Finningley. “You may remember the Heyford,” he recalled to a wartime press officer of the biplane. “It had a long, gaunt fuselage suspended from the underside of the upper wing. Consequently, it always looked as if it was upside down. But believe it or not, it was lovely to fly.”

By September 1939, Raphael was with 77 Squadron, based in Driffield, piloting what was then the “heaviest” of Bomber Command’s heavy bombers, the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley, also known as the “flying barn door.” On the night of Sept. 8-9, Flying Officer Raphael undertook his first operational sortie, a leaflet dropping mission—known as a “Nickeling”—to Essen in western Germany.

Running short of fuel, he force-landed at Buc, France, damaging the aircraft’s undercarriage in the process. It was an inauspicious beginning.

Several night sorties off the German coast followed. On Jan. 9, 1940, Raphael piloted one of two Whitleys engaged in a reconnaissance of western Germany. On more “Nickel” sorties to Bockum and Sylt in the north, his crew fired at searchlights. These operations garnered Raffy a Mention in Dispatches on Feb. 20. He was the first Canadian so honoured during the war.

On March 7-8, he dropped leaflets over Posen, Poland, a very long flight, which only the Whitley could perform. A similar mission to Warsaw followed on March 15-16; both trips necessitated a landing in France before a return to base.

The shadow boxing of the so-called “Phoney War,” the limited action in the early days of the conflict, ended on April 9, 1940, when the Germans occupied Denmark and invaded Norway.

By September 1939, Raphael was piloting what was then the “heaviest” of Bomber Command’s heavy bombers.

Bombs suddenly replaced leaflets and 77 Squadron deployed to Kinloss, Scotland, to attack airfields, oil refineries and shipping from as low as 1,000 metres (3,500 feet). In these northern climes, aircraft icing was a persistent problem.

“The first time was a piece of cake,” Raphael later recounted of the sorties. “There was scarcely any flak. So we went back three days later. By this time the Jerries had moved up in force. We went in fairly low—just as we had the first time. I was promptly picked up by 23 searchlights and about 60 multiple pom-poms opened up on us. We got away, but I don’t know how.”

The German offensive in western Europe that commenced on May 10, 1940, switched Bomber Command’s attention to the Low Countries and western Germany. Raffy was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) on May 17 for his earlier “Nickel” flights in Poland, which were described as “excellent both in prior planning and execution.”

Enthused by recieving a “gong,” Raphael volunteered for his next mission even though it was not his turn. On the night of May 18-19, he set off to bomb an oil refinery near Hanover, Germany, but he was attacked by a Messerschmitt Bf 110 at 2,700 metres (9,000 feet) about 60 miles off the Dutch coast.

A heavy burst of machine-gun and cannon fire wounded Raphael in both feet and set fire to one of his engines. The enemy aircraft then crossed the tail of Raffy’s Whitley and rear gunner, Aircraftman Harry Parkes, delivered a burst that sent the fighter into the sea in flames.

Raphael landed in the sea and the crew got into a dinghy. Luckily, their landing spot was noted by an Allied aircraft and after four hours they were picked up by destroyer HMS Javelin and taken to Yarmouth.

Raphael was hospitalized for two months, during which time he was promoted to flight lieutenant. He returned to operations on Aug. 11, 1940, this time with 10 Squadron, another Whitley unit. He completed 11 sorties before posting to instruct at a School of General Reconnaissance.

January 1941 brought a new posting in a different role—night fighting in Hurricanes with No. 96 Squadron. The Blitz was in full swing, but finding enemy aircraft in the dark was almost impossible without radar. Early in the year, Raffy was posted to 85 Squadron, based in Hunsdon, northeast of London. It was well placed to meet incoming attacks.

Better still, however, the unit was equipped with twin-engine Douglas Havocs with a top speed of 550 kilometres per hour and a cruising speed of 450. The Havoc was big enough to carry the earliest, though unreliable, airborne radars, and was armed with six .50-calibre machine guns in the nose. Some aircraft replaced the guns with a powerful “Turbinlite”—a 2.7 million candle searchlight powered by batteries in the bomb bay. The idea was to vector on to German aircraft using air and ground radar, illuminate the target, then have a Hurricane make the kill. It was a cumbersome method and soon abandoned.

As it happened, the Blitz was about to end as Hitler shifted forces eastward to attack the Soviet Union. The last big attack on London was on the night of May 10-11, 1941, when the Luftwaffe dispatched 571 bombing runs on the capital. It also marked Raffy’s first kill as a night fighter pilot. His combat report that night read:

“I took off from Hunsdon at 2335 hours on 10 May 1941 and was taken over almost at once by G.C.I. [Ground Control Interception—i.e. radar]. At about 0015 hours I was vectored onto an enemy aircraft over North London and Operator got a blip at maximum range (14,000 feet) slightly below and ahead. After four or five corrections I got a visual on enemy aircraft at about 600 yards slightly above and ahead. I closed to 100 yards and recognized enemy aircraft as an He-111. I fired one burst of four seconds at the starboard engine and the enemy aircraft immediately burst into flames and went into a left hand spiral dive to approximately 8000 ft, where it leveled out into a 60-degree dive to the ground. It appeared to explode just before it hit the ground. After one more attempt at an interception under control of G.C.I. I returned to base and landed at 0200 hours.”

Two days later (on May 13-14), he scored again. His first engagement at 1 a.m. was inconclusive; he overshot his target and lost contact. Soon afterward, without ground radar assistance, he found an He-111. It put up fierce resistance, but appeared to be out of control when Raphael lost sight of it; he was credited with a “probably destroyed.” Finally, at 2 a.m., ground control directed him to another He-111 that was picked up on radar. For a moment it appeared that Raffy might lose this one as well, but then it exploded in a great orange flash over Hunsdon—proof of a “destroyed” credit.

His radar operator on this and most subsequent occasions was Aircraftman (later Warrant Officer) William Nathan (Nat) Addison, who also accompanied Raphael on the first kill. In June 1942, an RCAF press officer reported Raphael’s appreciation of his teammate: “It wasn’t really my doing, you know. That young radio operator of mine has been responsible for our getting each one of them.” The press officer noted that the radio operator was a diminutive English warrant officer who was “a wizard with the secret detectors used by British night fighters.”

RAF censors cut all reference to “special detectors,” although by then the Germans were fully aware of Allied radar capabilities.

The crew’s next victory was on the night of June 23-24, 1941. Twice they were directed onto enemy aircraft approaching from the sea, and they lost contact both times. Finally, at just after 2 a.m., off Harwich, they intercepted a Ju-88. The enemy returned fire and put a bullet between Addison’s legs without wounding him. Raphael fired five bursts in some 20 seconds and the bomber was destroyed.

“If the Havoc had been armed with cannon, only one short burst would have been necessary,” remarked Raffy in his report, “and the enemy aircraft would not have been given an opportunity of returning fire.”

The following month was excellent. On the night of July 13-14, ground control guided them to within sighting distance of an He-111. Contact was made at about 2:20 a.m. The target took skilful evasive action, compelling Addison to give several course corrections.

Finally, Raphael was able to report: “Havoc closed to approximately 50 yards and fired a short burst with eight Brownings into the starboard engine, hits being observed. Return fire was experienced from the top rear position but the Havoc, being slightly below enemy aircraft, was not hit. The He-111 began a slight dive and the Havoc fired three more bursts into the enemy aircraft’s fuselage; hits were observed and fire broke out. The enemy aircraft then went into a very steep right hand diving turn, still on fire, and though the Havoc throttled back and followed the pilot could not keep close to the enemy aircraft. It was however seen to strike the sea in flames.”

The next day, July 15, Raphael was awarded a bar to his Distinguished Flying Cross; Addison received a Distinguished Flying Medal.

Promoted to squadron leader and appointed a flight commander, Raphael scored again on the night of Sept. 16-17. His victim this time was a Ju-88, shot down into the sea near Clacton. The plane belonged to a German night fighter unit. Three of the crew bailed out and were captured.

Raffy was promoted to wing commander on May 27, 1942, and appointed to take charge of 85 Squadron. “Lean, moustached, 26 years old, Raffy Raphael is the kind of man you would expect one of the RAF’s best night fighter pilots to be,” reported an RCAF press release at the time.

While Raphael was much respected, he was not necessarily loved. He was a strict teetotaller and non-smoker, and frowned on anything that might impinge on crew efficiency. He also lived away from the station, preferring to stay in a cottage with his wife and son. Meanwhile, Raffy strove to model the squadron on its First World War counterpart, when it had been commanded briefly by Billy Bishop. The aircraft were marked with the hexagon symbol that had been worn by SE5 fighters in 1918.

On July 30-31, 1942, Raphael claimed a “damaged” Ju-88 near Cambridge, but this was disputed by anti-aircraft gunners. More decisive was an action on August 2-3—he destroyed a Ju-88 (initially identified as a D0-217) near Dengie Flats, a gunnery range off the Essex coast. This was his last victory in a Havoc.

“If the Havoc had been armed with cannon, only one short burst would have been necessary.”

The squadron began converting to Mosquitos that month, with Raphael giving instruction to most crews while maintaining a high level of readiness himself, no mean feat when Luftwaffe activity was so reduced that keeping men sharp was a task in itself.

On Jan. 17-18, 1943, with Addison again, Raphael was scrambled after a “bogey” that proved to be a Ju-88 flying at some 1,800 metres (6,000 feet). His first burst of 20mm fire caused a large explosion in its port engine. He followed the burning bomber down through haze and finally pulled out at 100 metres (300 feet), just avoiding a crash in the sea.

Observers at Bradwell Bay confirmed that the Junkers had indeed gone into the sea. He was awarded a Distinguished Service Order on Feb. 2, 1943; the unpublished recommendation paid special tribute to his supervision of the squadron’s conversion from Havocs to Mosquitos. Addison received a DFC on Feb. 19.

That month Raphael also turned over command of 85 Squadron to an illustrious successor, Wing Commander John “Cat’s Eyes” Cunningham, the nickname inspired by his uncanny ability to spot enemy aircraft. Raphael moved on to staff postings, first at Castle Camps, then in April to Manston. He was very much a hands-on commander—he took off in Mosquitos to shoot down V-1 flying bombs in 1944 on June 29-30 and July 6-7. On Jan. 1, 1945, he was Mentioned in Dispatches again.

Raffy was promoted to group captain on Feb. 15, 1945, and posted to the command of Station Biggin Hill. He was killed on April 10, 1945, while flying a Spitfire. Many accounts say that Raphael collided with a Dakota aircraft, shearing off one wing, however, the other plane was actually an American C-46 Commando returning from a continental freight run with four crewmen aboard. In November 2006, Raphael’s medals were sold at auction for approximately 10,000 pounds ($24,000 Canadian).

Advertisement