When Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, the most immediate threat to the country was an attack on its shipping. That fear was so palpable that when periscopes were soon “sighted” in the St. Lawrence River, no one was surprised. A “submarine diviner” with a plumb-bob and a chart of the river was consulted to locate the U-boats. Then a mob of soldiers went down the river on a fire tug and a lighthouse tender to attack them. Apparently, the Germans got away.

When the U-boats came for real in 1942, they also got clean away. But not before sinking more than 20 ships, forcing the government to close the river to ocean shipping, and inflicting the most embarrassing defeat of the war on Canada. At least that’s the way the story has been told for the past 75 years. Recent scholarship suggests quite a different tale.

The context for the 1942 campaign in the St. Lawrence was a global war spiralling out of control, and a gap in Allied special intelligence. The Japanese seemed unstoppable in the Pacific and Indian oceans, U-boats were exacting a toll on Allied shipping in the Atlantic, and German armies were at the gates of Cairo and driving into the Caucasus. The Axis was in full cry and Allied resources were scarce. In February, the Germans changed their U-boat cypher, and for nearly a year the Allies were unable to read their tasking signals. As a result, only air patrols were active over the St. Lawrence on May 12 when U-553 sank the steamers Nicoya and Leto south of Anticosti Island. The navy issued a terse statement saying that the war in the Gulf of St. Lawrence had begun and that nothing more would be said. They were wrong about the second point.

Survivors from USS Chatham, torpedoed in the Strait of Belle Isle on Aug. 27, 1942, were rescued by HMCS Trail. All but 14 of the 562 passengers and crew were saved. [DND/LAC/PA-200329]

The sinking of Nicoya and Leto shocked Canadians and ignited a media frenzy and a firestorm in Parliament about unpreparedness and incompetence. Prime Minister Mackenzie King and the English-language media fed the fire in order to admonish Quebecers about their failure to support conscription and their less-than-enthusiastic support of Canada’s war effort.

By the time U-132 arrived in the St. Lawrence in July, convoys were running between Quebec City and Sydney, N.S. In the early hours of July 6, Kapitänleutnant Ernst Vogelsang torpedoed three ships of convoy QS-15, then crash-dived to escape the escort. At 60 metres, U-132 slammed into the cold seawater that lay under the warmer river water of the St. Lawrence. The dive stalled just as HMCS Drummondville bracketed the U-boat with depth charges, inflicting serious damage. When Vogelsang flooded his forward torpedo tubes to punch through the layer, the U-boat turned into a stone, plunging to 184 metres before Vogelsang could stop it. If Drummondville had destroyed U-132, 1942 might have gone much differently.

Vogelsang retreated to the northern gulf to effect repairs and to report on traffic in the Strait of Belle Isle; apparently, few ships were using the strait and operational conditions were “unfavourable.” By July 19, U-132 was back in the river off Cap-de-la-Madeleine, and sighted convoy QS-19 through the periscope the next day. None of the escort—the corvette HMCS Weyburn, the Bangor-class minesweeper HMCS Chedabucto and three Fairmile motor launches—saw the tiny attack periscope. Vogelsang hit the 4,367-ton freighter Frederika Lensen, breaking the ship’s back. The escort never found him, although air coverage kept U-132 submerged and prevented further attacks. Weyburn towed the Frederika Lensen to the bay at Grande-Vallée, Que., where it was beached and declared a loss. U-132 then turned for home.

The quiet—in the gulf, if not in Parliament and the press—lasted for about a month. Meanwhile, based on Vogelsang’s reports, the Germans sent three U-boats to the St. Lawrence. The first to arrive, U-517 commanded by Kapitänleutnant Paul Hartwig, reached the Strait of Belle Isle on Aug. 27. It’s likely that U-165 under Korvettenkapitän Eberhard Hoffmann arrived about the same time, and U-513 a little later. It soon became apparent that Vogelsang’s shipping intelligence was wrong.

When Hartwig submerged at daylight on Aug. 27 to patrol the northern entrance to the strait, three small convoys converged on him. The first was the “fast group” of convoy SG-6 (U.S. Coast Guard cutter Mojave and troop transport Chatham with 562 passengers and crew aboard) on its way to Greenland. The main body of SG-6 (consisting of three merchant vessels, plus the oiler USS Laramie and an aging auxiliary ship, the USS Harjurand, escorted by the USCG cutters Algonquin and Mohawk) was a few hours behind. Wedged between the two sections of SG-6 was a small Canadian convoy, NL-6 (two merchant ships escorted by the corvette HMCS Trail) en route to Goose Bay in Labrador. A lone Douglas Digby medium bomber from No. 10 Squadron RCAF, patrolled over NL-6.

At 8:48 a.m. local time, Hartwig hit Chatham with a single torpedo, after which cold seawater detonated her boilers. Hartwig saw none of this. The act of firing the torpedoes sent U-517 into an uncontrolled descent, and it was 40 minutes before Hartwig surfaced. By then, Chatham was gone (although virtually everyone got off) and the U.S. Coast Guard vessels were searching frantically for the perpetrator. Meanwhile, Trail prudently escorted her little convoy into Forteau Bay on the Labrador coast before joining the hunt.

Hartwig feared—needlessly—that he would be discovered by the escorts’ ASDICs, the British term for the underwater sonar-detection devices. “ASDIC conditions were bad,” reported Lieutenant G.S. Hall, RCNR, the captain of Trail. “Non-sub contacts could be obtained all around the ship on the riptides and water temperature gradients, and it was obvious that the effectiveness of an A/S screen would be greatly affected in this part of the Strait.” In fact, local currents were strong enough to push U-517 clear of the area by late afternoon, with little use of her motors.

Meanwhile, a major mix-up in proper reporting of the incident allowed the slow section of SG-6 to steam straight into the clutches of U-165. At 9:30 p.m. local time, Hoffmann’s torpedoes struck the SS Alyn, laden with dynamite and high-test fuel, and the oiler Laramie, filled with volatile aviation gas. Most of Alyn’s crew (except the stalwart Coast Guard gunners) abandoned ship quickly. Hartwig sank the derelict hours later. Miraculously, Laramie survived. Despite the prospect of imminent immolation, and at times ankle deep in gasoline, the USN crew got her back to Sydney.

A 1943 poster promotes war savings stamps to pay for depth charges. [LAC/C-091587]

The first contact the Allies had with Hartwig came on the night of Sept. 1, when he entered Forteau Bay on the coast of Labrador on the surface, and approached to within 20 metres of the wharf. As Hartwig withdrew, Weyburn passed U-517 in the dark, close enough for the deck watches to see one another. The corvette spun around as U-517 crash dived, but Weyburn’s ASDIC never found the sub.

Weyburn got another chance the next day while escorting the return passage of NL-6 off the north shore of the St. Lawrence. Hartwig had just fired torpedoes as Weyburn turned to attack him and opened fire. Hartwig was again forced into a crash dive, and again simply disappeared. “Weyburn didn’t get a sniff of him on ASDIC,” Tony German, a junior officer on Weyburn, later recalled, “although we’d seen him twice, large as life.” Hartwig’s attack sent the little 1,500-ton Canadian steamer Donald Stewart to the bottom.

Constant air patrols eventually encouraged both Hartwig and Hoffmann to move south into the choke point of trade along the Gaspé coast. (U-513 moved east along the north coast of Newfoundland and eventually attacked the anchorage at Wabana in Newfoundland’s Conception Bay.)

The worst of the Battle of the St. Lawrence was yet to come.

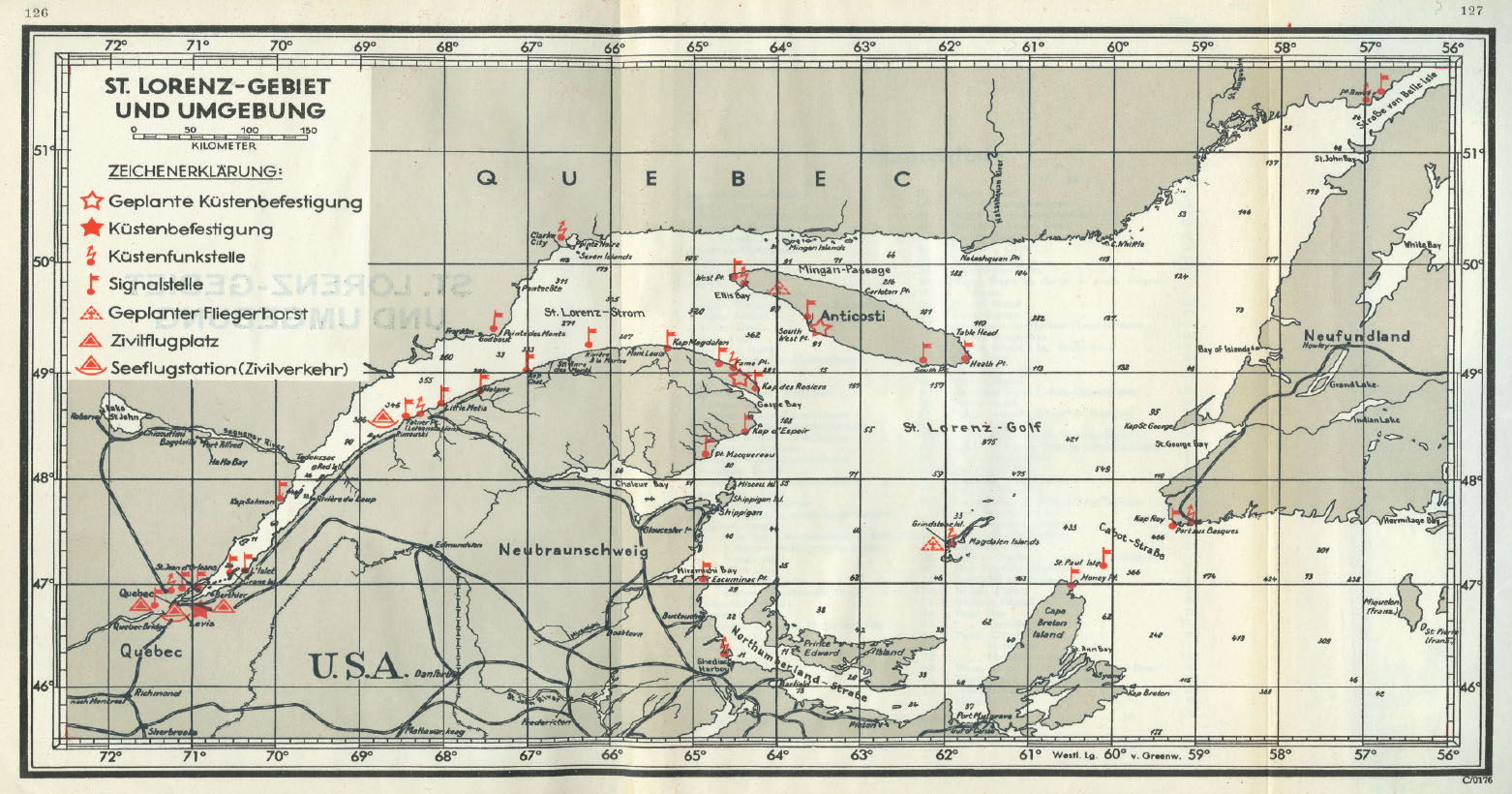

Navigation handbooks used by German submarine crews included this map of the Gulf of St. Lawrence locating lighthouses, gun emplacements and airfields. [CWM/19730174-002_b]

By the time Hartwig and Hoffmann arrived off Gaspé, the navy and the government had decided to close the gulf to oceanic shipping. This had little to do with lost ships. In fact, since May only six ships had been sunk by U-boats in the southern gulf and St. Lawrence River. The primary reason was the commitment of 17 corvettes to the looming Allied assault on North Africa, Operation Torch. “Letting corvettes go means routing freight by the river will have to stop for this season,” Mackenzie King stated.

The British were also anxious to shut down the 1,600-kilometre convoy route to Canada’s inland ports. Allied shipping losses in 1942 were staggering, and carrying capacity could be saved by routing Canadian trade by rail to East Coast ports. The RCN also knew that the complex hydrography of the river and the gulf could not be solved by the technology of the era, while the canalizing effect of the geography forced convoys into predictable and easily intercepted tracks. As things turned out, the heaviest and most dramatic losses in the St. Lawrence therefore occurred after the decision was made to close it to oceanic shipping.

In the meantime, the solution to U-boats in the St. Lawrence was airpower. By early September 1942, the RCAF had reinforced its forces in the St. Lawrence. Six Hudson bombers were now operating from Mont-Joli, Que., and a special “striking force” of three Hudsons were deployed to Chatham, N.B. The latter were among the first Canadian-based maritime patrol aircraft to be painted all white and to use a higher patrol altitude—which made them significantly harder to see. This combination allowed Pilot Officer R.S. Keetley to surprise Hoffmann on the surface south of Anticosti Island on Sept. 9. Keetley’s patrol had been initiated after the disappearance of the little auxiliary escort vessel HMCS Raccoon (shattered by torpedoes from U-165). Hoffmann escaped, in part because Canadian-based aircraft still lacked depth-charge pistols suitable for attacking a surfaced U-boat.

Then on Sept. 11, Hartwig also announced his presence by sinking an escort, HMCS Charlottetown, in broad daylight just off the Gaspé coast. Then Hartwig and Hoffmann launched a tag-team attack on convoy SQ-36. By Sept. 14, Hartwig was off Cap-des-Rosiers, Que., ready to intercept SQ-36, the largest St. Lawrence convoy of the season with 22 ships headed for Quebec. It also had the largest escort yet: the British destroyer HMS Salisbury and the Canadian corvette HMCS Arrowhead, both with modern radar, as well as the Bangor-class HMCS Vegreville and several motor launches.

On the afternoon of Sept. 15, Hartwig used the river current to drift down—submerged and silent, with no telltale feather of spray from his periscope—unseen and unheard onto the convoy. Salisbury passed within 150 metres of U-517 just minutes before Hartwig coolly fired four torpedoes. Two ships were struck and both soon sank. Searches and counterattacks were fruitless. The British captain of Salisbury later complained about how poor the sonar conditions were in the river; this was not news to his Canadian colleagues.

Hoffmann, alerted by Hartwig of SQ-36’s progress, was ready when the convoy reached Cap-Chat, Que., in the early hours of Sept. 16. He launched a daylight submerged attack, although the ships in the convoy saw his periscope and fired on it as Hoffmann completed his firing sequence. Two ships were hit: the British SS Essex Lance was salvaged, but the Greek merchant ship Joannis sank in 10 minutes. Undeterred by the escort, Hoffmann hung on to hit the American merchant ship Pan York, which was also salvaged. With all his torpedoes expended, Hoffmann headed home. He never made it; U-165 was sunk as it reached the Bay of Biscay.

“St. Lawrence Convoy” by Thomas Beament, an official war artist who served with the Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reserve during the battle in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. A merchant ship, a motor launch and a minesweeper are shown. [Thomas H. Beament/CWM/19710261-1049]

Hartwig, however, wasn’t done. After a few days off Newfoundland shifting torpedoes stored outside his hull into his forward torpedo room, he returned to the Gaspé. By midday on Sept. 21, he was tracking SQ-38 off Cap-des-Rosiers. Hartwig thought he was safely submerged, but the fickle water conditions left a portion of his conning tower exposed. Hartwig later admitted trouble maintaining a steady depth: “Those water layers!” he recalled.

HMCS Georgian was about to ram U-517 when it crashed dived. Georgian then conducted a deliberate depth charge attack, and was turning to regain contact when U-517 suddenly breeched the surface, rolled onto its side, and then submerged.

Acting Lieutenant-Commander A.G. Stanley, RCNR, kept Georgian at it for the rest of the day, until all his depth charges were expended. The staff in Halifax agreed with Stanley’s assessment: U-boat sunk. But Hartwig got away—again. He moved north to clear the area and repair damage, then plunged again into the traffic at the entrance to the river.

By the time Hartwig returned in late September, the RCAF had finally shifted whole squadrons from Nova Scotia to the St. Lawrence, adding an additional 15 Hudsons and 20 Cansos to the area. Most were radar-equipped and provided air cover at night. From now on, it was the U-boats who were the hunted. In one 24-hour period on Sept. 25-26, Hudsons caught Hartwig on the surface seven times—including at night—and attacked him three times. In the first attack, three of the four depth charges failed to release, while the one that did shook U-517 badly; had all four fallen that close, U-517 would have been sunk. After another attack, U-517 resurfaced to find a depth charge lodged in its deck; had Hartwig gone deeper, his U-boat would have been destroyed. His luck held again several days later when a Hudson flown by Flying Officer M.J. Belanger, bracketed U-517 with four depth charges. Belanger reported, “One large explosion occurred around the hull.” U-517’s motion stopped, her bow came out of the water and then the sub settled by the stern. It was reported sunk—again.

Hartwig’s radio transmissions soon indicated otherwise. He headed home on Oct. 6, ending one of the most remarkable U-boat cruises of the Second World War. The navy and the RCAF had nearly killed him several times. But after mid-September, the RCAF effectively suppressed him. This was a portent.

Survivors of a torpedoed merchant ship arrive at St. John’s aboard convoy escort HMCS Arvida on Sept. 15, 1942.

It was always assumed that the quiet fall that followed Hartwig’s departure was a combination of the closure of the gulf and a resulting lack of German interest. But the gulf never closed and the Germans kept coming. Historians have long known that the formal closure of the gulf to oceanic shipping announced in September meant little in reality: the SQ-QS convoys ran until the end of the shipping season. The gulf remained a busy place in the fall of 1942.

In fact, recent research reveals that the Germans were so convinced of the importance and vulnerability of the St. Lawrence that they ordered another wave of U-boats into the area in mid-September. The scale of this final German assault was lost in undecrypted signal traffic until the new RCN official history, No Higher Purpose, was published in 2002. A decade later, Roger Sarty laid it out in even greater detail in his book War in the St. Lawrence. It is not a tale of great drama, but rather of a quiet victory by intelligence and operational staffs, routine and targeted patrols, growing skill on the part of the defenders and new technologies. No one noticed at the time but the Germans.

The first of the final wave to arrive, U-69 commanded by Oberleutnant Ulrich Graf, reached Cabot Strait on the night of Sept. 29-30. U-69 carried the new Metox radar warning system. It was effective at detecting radar waves of the type then carried by most aircraft and in common use by the RCN. Metox was non-directional and gave no sense of the distance to the transmitting radar set; all it did was alert submariners to the presence of radar transmissions so they could dive. Metox induced paranoia in U-boat captains in the gulf in the fall of 1942; it seemed the air was filled with radar waves.

U-69 achieved initial success in the St. Lawrence River on Oct. 9, when Metox alerted Graf to the presence of convoy NL-9. Graf stalked the convoy in the dark for several hours amid the continuing alarms from his Metox. The Canadian radar operators “must be asleep!” he commented. They weren’t, of course. But the radar of the corvettes HMCS Hepatica and HMCS Arrowhead could not easily detect so small a target as a surfaced sub, while Graf could use the transitions to find their convoy. Graf escaped detection and after several hours fired two torpedoes from the long range of 2,000 metres. One sank the tiny steamer Carolus.

That was all U-69 accomplished and Graf quickly confirmed what Hartwig knew already—the Gulf of St. Lawrence was now an unhealthy place for U-boats. Air patrols were guided by increasingly effective naval intelligence derived from high-frequency radio direction finding. Harried by radar-equipped aircraft and suffering compressor problems, U-69 retreated—submerged—to Cabot Strait. Like Hartwig, Graf was driven out, and he would not be the last.

As U-69 abandoned the gulf, U-106 under Kapitänleutnant Hermann Rasch crossed her path heading west. The sub had entered Cabot Strait on Oct. 10 and the next day sank the 2,140-ton steamer Waterton from the Corner Brook-to-Sydney convoy BS-31 near St. Paul Island, N.S. BS-31’s escorts, the armed yacht HMCS Vision and a Canso bomber, delivered frighteningly quick and accurate depth charge attacks on U-106. By the time U-106 reached the St. Lawrence River, Rasch’s crew was totally spooked by constant Metox warnings and air patrols.

“Strong defenses since 16.10,” U-106’s log noted, “Search units using ASDIC.… Air surveillance co-operating with surface search forces and also operating everywhere without surface forces.” U-106 soon abandoned the gulf.

U-43 followed Rasch by a few days into the entrance to the river and encountered the same oppressive patrolling. But Oberleutnant zur See Hans-Joachim Schwantke decided to stay on and see what luck he might have. It was all bad. U-43’s failed attack on SQ-43 off Gaspé on Oct. 21 resulted in what Sarty described as “one of the most effective counterattacks during the St. Lawrence battle.”

Six depth charges from the Bangor-class HMCS Gananoque knocked out lights, blew the battery circuit breaker and activated a torpedo in one of U-43’s stern tubes. Schwantke pushed his sub down to 130 metres to avoid what he thought was a co-ordinated attack. When Gananoque failed to regain contact after the initial attack, her crew believed U-43 was just another non-sub contact, a “shoal of fish or a rip tide.” According to Sarty, Ganaoque’s action nonetheless “reflected the improved readiness on the part of escorts” by late 1942, and saved both SQ-43 and QS-40 (in the area the next day) from attack. Schwantke fared no better when he tried to attack LN-12 three days later, and U-43, too, abandoned the gulf at the end of the month.

Meanwhile, German Admiral Karl Donitz ordered two more type IX U-boats into the gulf in October. U-183 and U-518 both arrived in Cabot Strait on Oct. 18, where they were to wait until the new moon before venturing into the gulf. In the end, U-183 simply refused to chance it. Opining to headquarters that traffic was “completely dead” and air patrols oppressive, U-183 moved south of Nova Scotia instead. Only U-518 braved the angst of near-continuous Metox alerts to push deep into the gulf in November, but it had a special mission—to land a spy on the Gaspé coast. Once that was accomplished, U-518 didn’t linger. Instead it headed for Conception Bay to attack the iron ore ships at Wabana.

The departure of U-518 from the gulf in mid-November ended the final phase of the 1942 campaign, and it was a clear Canadian victory. Six U-boats were ordered into the gulf in October and November, four made the effort. They sank three ships, a dismal reward for the effort. Sarty concludes emphatically that “Canadian forces shut down the U-boat assault in the St. Lawrence.”

Historians have long known that the loss rate of convoys in the Canadian coastal zone in 1942 was negligible—only 1.2 per cent. Moreover, of the 100 SQ-QS convoys that plied the St. Lawrence in 1942, only 12 were intercepted by U-boats. However, because of the gap in intelligence in 1942, Canadian authorities had no notion that a final wave of six U-boats was ordered to the St. Lawrence in the fall of 1942, nor that they were either hounded out by Canadian defences or simply declined to try their luck. It seems that Canadians won a quiet but decisive victory in the St. Lawrence in late 1942.

Top Photo: A depth charge explodes off the stern of a Fairmile motor launch on patrol in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. German U-boats sank 20 ships in the gulf in 1942, prompting an outcry over Canada’s unpreparedness. [Kenneth G. Fosbery/DND/LAC/PA-190572]

Advertisement