Survivors are taken ashore after their rescue from SS Athenia. [Independent News and Media/Getty Images/534277070]

Britain declared war on Germany at 11 a.m. on Sunday, Sept. 3, 1939. At just after 7 o’clock that evening, Captain James Cook of the passenger liner SS Athenia joined his first-class guests for dinner.

While the ship had actually gotten underway two days earlier—en route from Glasgow to Montreal via Belfast and Liverpool—Cook had felt that the urgency of the international situation demanded his presence on the bridge. But by about mid-afternoon Sunday, as Cook told one passenger, they should be far enough into the Atlantic Ocean northwest of Britain and Ireland to be out of danger.

At 7:40, just as the evening meal was being served, a violent explosion destroyed the engine room, plunging the dining room into darkness, sending tables and chairs skidding across the deck, and causing the ship to list to port and begin settling by the stern. The German submarine U-30 had attacked Athenia.

For Canadians, Britons and even Americans, this is when and where the Second World War war began. The Germans were ready. A flotilla of 19 U-boats had sailed between Aug. 19 and 22 and were on station around the British Isles when the crisis over the German invasion of Poland reached its climax.

In fact, Germany was committed by treaty not to sink civilian passenger ships, but as dusk fell that evening, the captain of U-30 sighted Athenia running without lights and sailing in a zig-zag anti-submarine pattern. He concluded it was an armed merchant cruiser. U-30 fired four torpedoes, one of which hit Athenia on the port side, striking the ship a mortal blow.

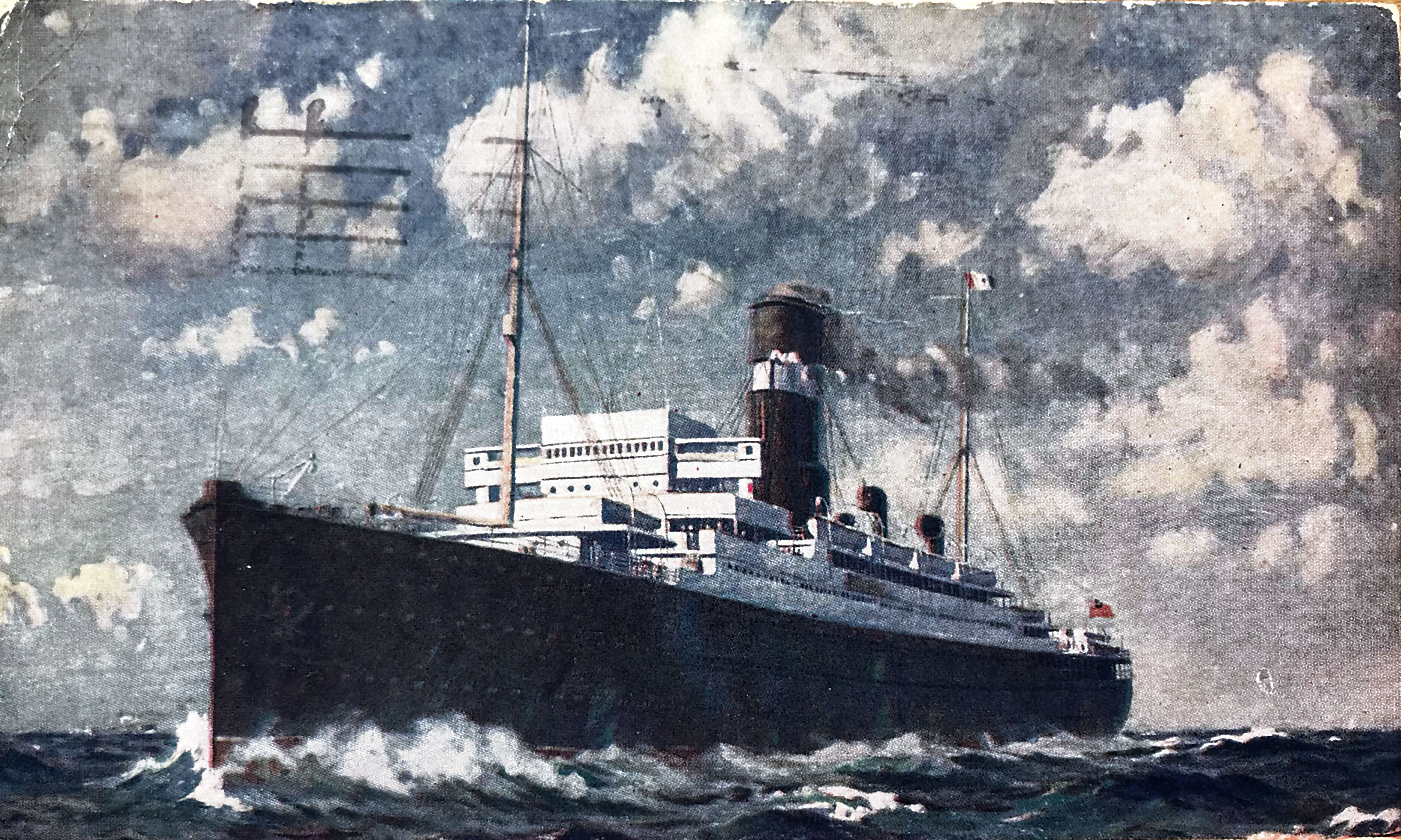

SS Athenia sailed from Scotland en route to Montreal on Sept. 1, 1939. The ship was torpedoed on Sept. 3 about 400 kilometres northwest of Malin Head, County Donegal, Ireland. [Courtesy of Francis M. Carroll]

Athenia was a Donaldson Line ship, built in 1923, servicing the northern United Kingdom ports of Glasgow, Belfast and Liverpool on a regular route to Quebec City and Montreal. Unlike the large, glamorous luxury liner RMS Queen Mary on the Southampton-to-New York run, Athenia and her sister ships usually carried families visiting grandparents in Scotland and northern England, and students, tourists and immigrants.

The international crisis in August—failed alliance talks between Britain, France and the Soviet Union followed by the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact of Aug. 23—had resulted in a crush of people attempting to get home before hostilities broke out. So Athenia had more passengers than usual.

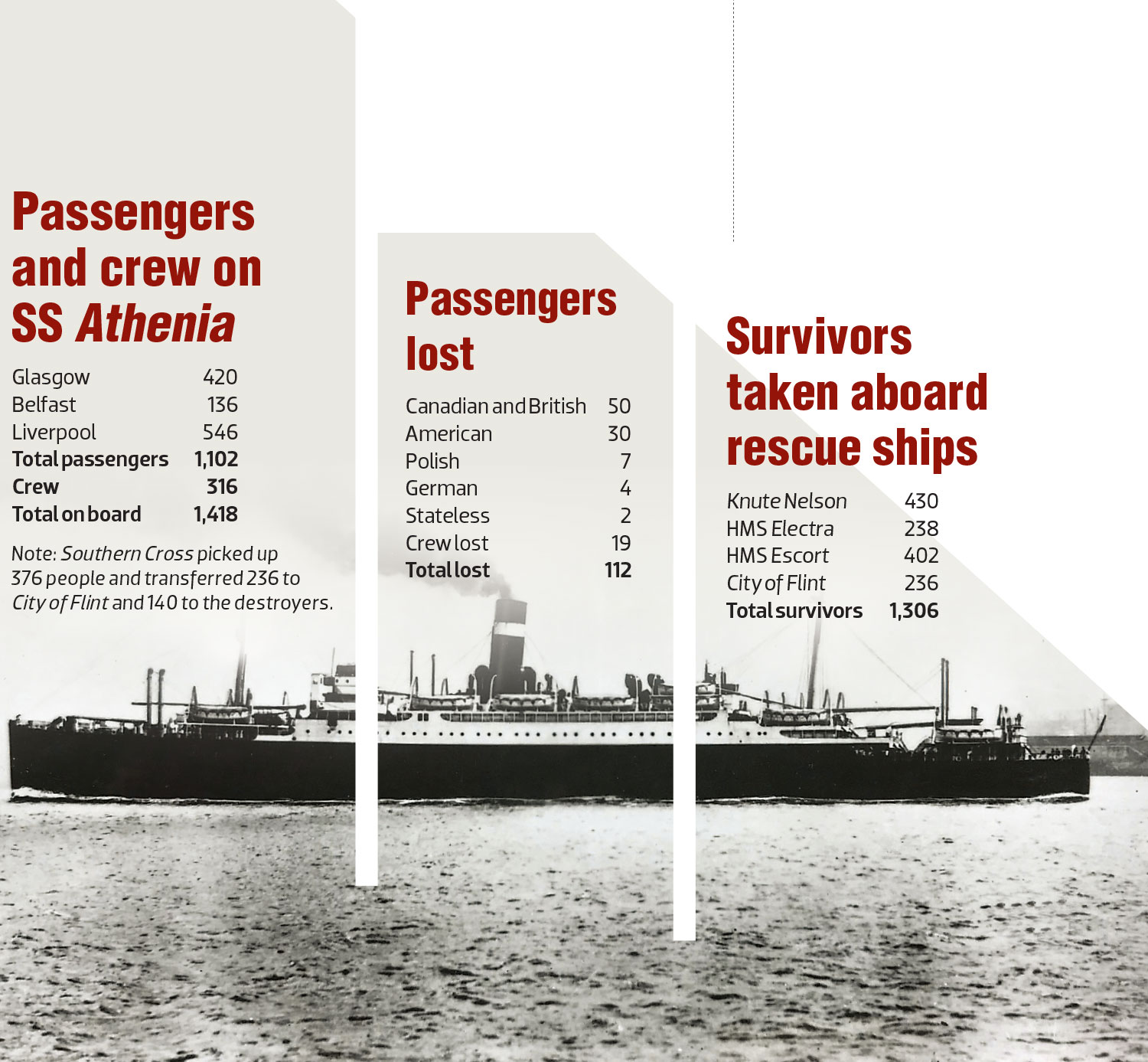

The ship left Glasgow on Sept. 1, picked up more people off Belfast that evening, and then went on to Liverpool to receive its final passengers. Some 1,102, along with 316 crew, put to sea at 4 p.m. on Sept. 2. Athenia headed through the North Channel around Ireland and was well out into the Atlantic before war was declared.

Normal shipboard routines—church services and seating assignments in the dining rooms—carried on, although some wartime precautions were taken: portholes were covered and lifeboats were readied for use. Nevertheless, the explosion of the torpedo took everyone by surprise.

While waiting to go to dinner, young Donald Wilcox of Dartmouth, N.S., had made his way to the very peak of the ship’s bow and was watching the waves curl away from the prow when the ship rose up several feet and then fell back down sharply. “I was almost thrown off my feet,” he remembered years later.

Three women follow a soldier carrying a baby down the gangway of the Norwegian ship Knute Nelson which delivered survivors to Galway, Ireland. [National Library of Ireland]

All the lights went out and the ship stopped dead in the water and began settling by the stern. The engine room, the galley, parts of the dining rooms and many staterooms flooded. People were separated and groped in the dark to find their way to the open decks before emergency lights came on. Crew members guided people with matches and flashlights, while James A. Goodson, 18, of Toronto, whose holiday in Europe had been cut short, swam through a flooded section of the ship to rescue struggling passengers, guiding them to what remained of the stairs.

All 26 lifeboats were launched, although there were difficulties in getting many of the women and children into them. Fortunately, distress signals were received by ships reasonably close by. Shortly after midnight, Norwegian freighter MS Knute Nelson arrived on the scene, followed by Swedish steam yacht Southern Cross, owned by the Electrolux millionaire Axel Wenner-Gren. They began taking on survivors from the lifeboats, looking after the injured and offering food and hot drinks.

As the night wore on, three Royal Navy destroyers reached the scene, HMS Electra, HMS Escort and HMS Fame. They also picked up survivors and provided food and dry clothing. In the morning, the American freighter SS City of Flint arrived and took people from Southern Cross and the destroyers before heading back across the Atlantic bound for Halifax. Knute Nelson took survivors to the Irish port of Galway, and the navy destroyers sailed back to Scotland, sending their passengers to Glasgow. At about 11 a.m. on Monday, Athenia heeled over and sank stern first.

A young boy is passed down the gangway from Knute Nelson in Galway, Ireland. [Peter Power/Toronto Star]

The survival of 1,306 people was something of a miracle, thanks in part to the discipline and training of Athenia’s crew in getting all the lifeboats launched, the proximity of several rescue ships and the relatively moderate seas. Tragically, 112 people were killed, either in the initial explosion or in the difficult circumstances in the lifeboats.

Among those lost was 10-year-old Margaret Hayworth of Hamilton, Ont., who was hit on the head by a fragment as the torpedo exploded and died six days later despite medical treatment on City of Flint. She was buried in Hamilton at a large public service.

While Knute Nelson was rescuing survivors, its propeller sliced through one of the lifeboats. Among those killed was William Allan, a Toronto Presbyterian minister who had a popular devotional radio program. Hanna Baird of Verdun, Que., a stewardess on Athenia, also did not survive and is regarded today as the Canadian Merchant Navy’s first Second World War fatality. The death of these Canadians was a shocking start to the war.

For many survivors, particularly families separated while getting into lifeboats, the ordeal was not yet over. Georgina Hayworth successfully got into a lifeboat with her fatally injured child Margaret, but her younger daughter Jacqueline lost hold of her skirt and was placed in a different lifeboat. “It was the worst day of my life, being separated from my mother,” Jacqueline remembered years later.

David Cass-Beggs, who had accepted an appointment to teach electrical engineering at the University of Toronto, and his wife Barbara had their three-year-old daughter Rosemary with them. When it was uncertain whether there would be sufficient lifeboat space for all the passengers, the parents put their daughter into the hospital boat. They eventually boarded a lifeboat, however, and were picked up by Knute Nelson and taken to Galway, while little Rosemary was placed on City of Flint, headed for Halifax. Fortunately, Winifred “Auntie” Davidson of Winnipeg looked after Rosemary until family friends received her in Montreal.

Margaret Hayworth (at left) and her younger sister Jacqueline of Hamilton were aboard SS Athenia when it was hit. Margaret was struck by shrapnel and died six days later. [Getty Images/165324337]

Among the refugee passengers picked up by Knute Nelson and brought to Galway were Rudolph and Anni Altschul, who had fled Prague when the Germans occupied Czechoslovakia in March 1939. Anni, in a state of shock, kept telling her husband that she had a cousin in Ireland. In this chaotic situation, such a detail seemed irrelevant to Rudolph, but when they landed at Galway and were met by a large, hastily organized party of aid workers, Anni simply called out “Edith,” her cousin’s name, and mira-culously she appeared among the volunteers.

Authorities in Galway and Glasgow received the survivors with great kindness and generosity. Medical aid was provided, hotels opened up rooms, clothing was collected, telephone and telegraph services were made available. Both the Canadian and American governments sent official thanks to the Irish and British governments, especially to the cities of Galway and Glasgow for their immediate help. Vincent Massey, the Canadian High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, also requested funds from the Canadian government, and the prime minister and the Canadian Red Cross authorized assistance.

Seriously wounded Athenia passengers (left) are transferred mid-Atlantic from the City of Flint to the U.S. Coast Guard cutters Bibb and Campbell, which had medical facilities. [AP/3909131264]

Massey arranged for Canadian Pacific ships to bring people back to Halifax and Montreal. SS Duchess of Atholl sailed on Sept. 13 with 104 survivors and SS Duchess of York on Sept. 14 with 163; SS Duchess of Richmond and SS Duchess of Bedford left later. The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom, Joseph P. Kennedy, sent his 22-year-old son, John F. Kennedy, north to Glasgow to look after American survivors. Beside these assurances, the Americans also sent funds to assist their survivors and the State Department chartered SS Orizaba to bring people home.

The arrival of the survivors in Canada produced pain, horror, relief and joy. City of Flint was met at sea by two U.S. Coast Guard cutters and escorted into Halifax Harbour on Sept. 13. A large crowd greeted the ship, led by the premier of Nova Scotia, Angus L. Macdonald, as well as the minister of health, the mayor of Halifax, officials from the Royal Canadian Navy, RCMP, Red Cross, Boy Scouts, a number of doctors and nurses, 40 newspaper reporters and the American consul general.

Facilities were set up to give survivors fresh clothes, a hot bath, meals and transportation to Montreal and then home. A photograph of the hastily made coffin of young Margaret Hayworth being carried from City of Flint stirred the nation and brought home the cruelty of war.

U-30 returns to its base in Wilhelmshaven, Germany. Kapitänleutnant Fritz-Julius Lemp is wearing the white cap. [National Library of Ireland]

The destruction of this passenger ship in the first hours of the war shaped public opinion throughout the English-speaking world. Given the time difference in Western Canada, the Winnipeg Tribune printed special evening editions on Sunday, Sept. 3, announcing BRITISH SHIP SUNK BY ENEMY TORPEDO. The following day, The Globe and Mail ran headlines ATHENIA IS TORPEDOED, LINER CANADA-BOUND, 1,400 ABOARD, SUNK OFF HEBRIDES. The New York Times lead story announced BRITISH LINER ATHENIA TORPEDOED, SUNK; 1,400 PASSENGERS ABOARD, 292 AMERICAN. In London, The Times asserted THE TORPEDOED ATHENIA. NO WARNING GIVEN AND ALL RULES BROKEN. In Athenia’s home port, the Glasgow Daily Record & Mail declared that “the German leopard has not changed its spots.”

The German government publicly denied it had any U-boats in the area and charged that the British had destroyed the ship in order to bring the U.S. into the war. Public opinion in all three countries, however, was overwhelmingly convinced that the Germans had sunk the ship. This conviction was confirmed by the sinking of naval and merchant vessels in the following weeks.

The shock of the sinking pushed governments into immediate action. Winston S. Churchill was brought into Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s government on Sept. 3 as First Lord of the Admiralty. On Monday, Churchill gave Parliament the details of what was known about the sinking of Athenia and explained Germany’s obligations under the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935.

In the evening, he met with Admiral of the Fleet Sir Dudley Pound and senior admiralty staff to assess the U-boat situation and the disposition of British merchant ships. Pushed by the news of Athenia and its survivors, the cabinet met each day and discussed these matters. On the evening of Sept. 6, Churchill and the admiralty staff agreed to implement convoys for merchant ships to begin the following morning.

Initially, ships sailing from the Thames River and along the east coast would be organized into convoys, but the orders were quickly broadened to all major ports and incoming ships as well. (In the First World War, convoys had not been implemented until June 1917.)

The Illustrated London News commissioned an artist to depict a lifeboat drifting away from the foundering vessel. [Alamy/KKFP4K]

By Sunday evening, Canadians had learned of Britain’s declaration of war. Early on Monday morning, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was informed of the sinking of Athenia. He then called a meeting of Cabinet and reconvened Parliament on Thursday, Sept. 7. The question of war with Germany was the key issue for Parliament and the fate of Athenia became one of the arguments in its favour.

Ernest Lapointe, minister of justice and King’s Quebec lieutenant, reasoned that while some people had been claiming Canada had no stake in such a war, “at that very moment an enemy submarine was torpedoing the liner Athenia, which was carrying over five hundred Canadian passengers who might have lost their lives.”

Speaking for the opposition, Thomas L. Church, member of Parliament for Broadview in Toronto, said the passengers on Athenia were not given a chance to vote on whether to go to war or not when their ship was torpedoed. “I say we owe a duty to those passengers tonight,” he argued. Parliament voted for war on Saturday, Sept. 9, and the declaration was cabled to High Commissioner Massey in London, who took it to King George VI for his signature on Sunday morning.

Captain Joseph Gainard of the City of Flint comforts Elizabeth Campbell, comforts one of the young survivors. [Courtesy of Francis M. Carroll]

America had not been directly involved in the Czechoslovak and Polish crises of 1939, although President Franklin D. Roosevelt had attempted then to revise the existing neutrality laws to allow the U.S. to support friendly democracies in the event of war. Anti-interventionist sentiment in Congress was too strong to make any changes to the existing restrictions. However, with the outbreak of the war on Sept. 3, the sinking of Athenia with Americans on board, the dramatic newspaper stories of the American freighter City of Flint bringing Canadian, American and European survivors to Halifax, and the national popularity of the ship’s gallant captain, Joseph A. Gainard, the U.S. Congress passed a new Neutrality Act in November 1939 that allowed the sale of munitions and strategic goods to belligerents on a “cash and carry” basis.

The sinking of Athenia was soon overshadowed by the expansion of the war at sea and elsewhere and even greater tragedies than this. Nevertheless, the sinking marks the beginning of the war in the West. The attack may have been an error in judgment by the U-boat commander, but it touched Canadians, Americans, Britons and Europeans within hours of the declaration of war. This was the beginning of Canada’s war. Eighty years later, the remaining survivors are still haunted by that traumatic experience.

Advertisement