Operation Drumbeat

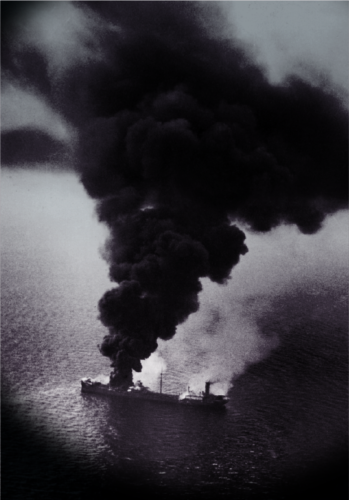

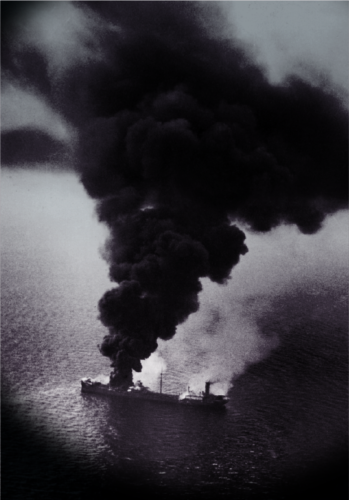

U-boats targeted East Coast shipping in the first half of 1942 In the early hours of Jan. 12, 1942, wireless stations around the North Atlantic picked

U-boats targeted East Coast shipping in the first half of 1942 In the early hours of Jan. 12, 1942, wireless stations around the North Atlantic picked

In a U-boat rampage off the East Coast in 1918, the schooner Dornfontein was captured and burned On Aug. 3, 1918, a small boat carrying

When Nicholas Monserrat titled his classic account of the Battle of the Atlantic The Cruel Sea, it was no accident. Nearly half of the Royal

Story by Marc Milner Photography by Stephen J. Thorne The word comes in late in the evening: the president and the provisional government of “West

Canada’s role following D-Day was vital to the success of Operation Overlord The problem with the well-known story of Canada’s role in Operation Overlord, the

When Canada declared war on Germany in September 1939, the most immediate threat to the country was an attack on its shipping. That fear was

Get the latest stories on military history, veterans issues and Canadian Armed Forces delivered to your inbox. PLUS receive ReaderPerks discounts!

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Free e-book

An informative primer on Canada’s crucial role in the Normandy landing, June 6, 1944.