Image credits: Lieut. G. Barry Gilroy/DND/LAC/PA-134390

part five

liberation

ISAW A TANK in the distance, with one soldier’s head above it, and the blood drained out of my body, and I thought: Here comes liberation,” recalled a Dutch teenager describing the arrival of the Canadians. “There was a big hush over all the people, and it was suddenly broken by a big scream, as if it was out of the earth.”

The cities and villages had gone silent during the Hunger Winter, with most people being too cold and hungry to move around. The colour had drained out of life. But now it returned, brought by the liberators. The liberation not only delivered the Dutch from Nazi tyranny but also a creeping death that was almost upon them.

“This was the first time the Dutch had seen Allied soldiers. What a welcome we got!” said Lieutenant Reg Roy. His Cape Breton Highlanders had entered Zuiderzeeweg in an armoured car in the dead of night. They were shocked at the greeting. “The town went mad, completely mad, with joy. People thronged the streets with foolish cheering, waving, kissing and crying. Flags and streamers appeared in every house as if by magic.”

The scene of liberation was repeated again and again, with great crowds surging forward to greet the Canadians as they rolled into town. The newly liberated waved Dutch flags and homemade Union Jacks and Red Ensigns. Men and women cried and cheered; children climbed onto the armoured vehicles, which were soon decorated with flowers.

Children climbed onto the armoured vehicles, which were soon decorated with flowers.

“We experienced the moment of our liberation as an inexpressible feeling of relief that we had thrown off this ever-present bondage we had endured for five long years,” said Gertrude Joldersma, then a young Dutch girl, recalling her excitement when the Canadians liberated her farming community near Holten on April 10.

The Canadians were amazed at the response, but soon also came to understand the magnitude of their actions. They had left many comrades behind in the year of battle, best friends buried along the liberation route or sent to hospitals with frightful wounds. Sunburned, windswept Canadians, some with uniforms in tatters, suddenly found themselves victors and liberators.

In April 1945, the Canadians also began to encounter work camps filled with slave labourers. Russian, Polish and other prisoners had been kept in desperately bleak conditions. Poorly fed and overworked, surviving prisoners pointed to mass graves of thousands who had succumbed to the ill treatment, or had been summarily executed. The health of most prisoners was more wretched than the Dutch citizens. Members of the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps administered care to thousands of these patients.

900

Number of people killed in the German bombing of Rotterdam on May 14, 1940

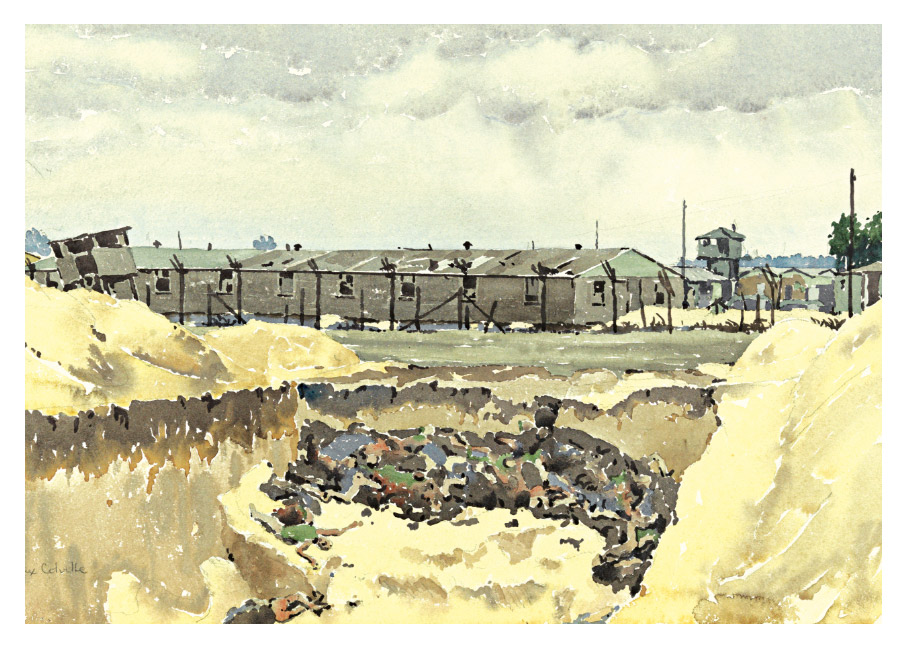

The most jarring discovery for the Canadians was Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in northern Germany. Liberated first by British troops on April 15, 1945, Canadians arrived over the coming days to deal with a mass of helpless inmates. The stench of 13,000 decomposing corpses in open graves assaulted the senses. The survivors—walking skeletons, many close to death from typhoid, typhus or tuberculosis—were a traumatic sight. The camp assaulted Canadians who encountered it.

A gaping burial pit at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp was depicted in watercolour by war artist Alex Colville. The camp was liberated by Canadian and British troops on April 15, 1945.

Poorly fed and overworked, surviving prisoners pointed to mass graves.

“We were shocked. In fact, we couldn’t really believe it,” said Charles Scot-Brown, a CANLOAN officer serving with the British army. He had heard rumours of German death camps, but could not comprehend the meaning until he went to Belsen. “It was that horrible. Fifteen to twenty thousand mobile skeletons, and thousands not moving at all.”

The lifeless, twisted bodies would haunt him forever. Official Canadian photographers, film crews and war artists were sent to document the camp. Film, photographs and eyewitness accounts would soon emerge attesting to other camps, including Buchenwald and Auschwitz—and the world shuddered.

“On the first day, I made a drawing of some women, dead from starvation and typhus, lying outside one of the huts,” artist Charles Comfort recalled. “While I drew, the group of bodies was added to as more people died and were feebly dragged out of the hut by the inhabitants who were themselves more dead than alive.”

Most Dutch Jews had been rounded up and sent to death camps, but on April 12, the 14th Canadian Hussars and South Saskatchewan Regiment overran Westerbork transit camp, north of Apeldoorn. Some 750 ragged Jews wept with joy as the Canadians gave them back their lives.

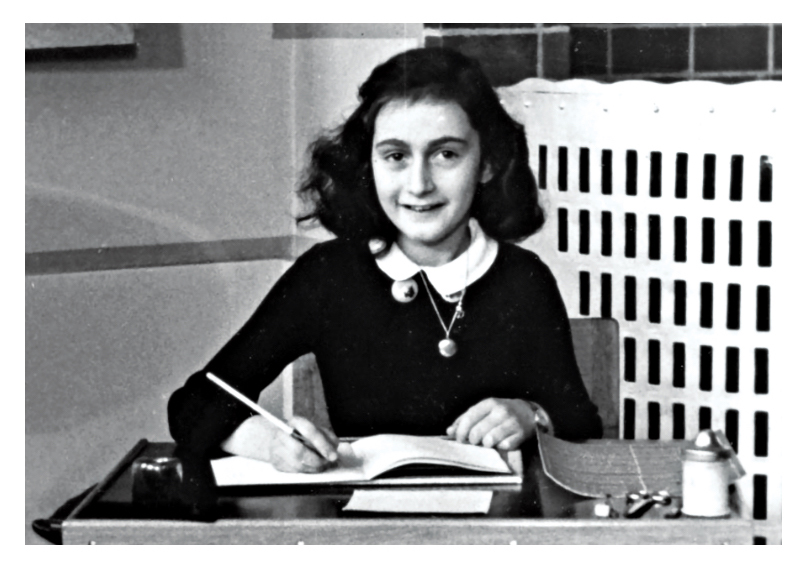

Westerbork was a holding camp for Dutch Jews being sent to Auschwitz, Treblinka and other camps. After two years of hiding and keeping her famous diary, the young Dutch Jewish girl Anne Frank passed through Westerbork before being transferred to Belsen, where she died only a few months before the liberation.

They had left many comrades behind in the year of battle.

British troops guard members of the Schutzstaffel (SS) after liberating the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Germany.

800,000

Number of Schutzstaffel (SS) members in 1940-44

Anne Frank, whose wartime diary became a defining chronicle of the Nazi occupation, is pictured at school in Amsterdam in 1940.

Estelle Tritt-Aspler, a nurse in the Royal Canadian Army Medical Corps, served in the Netherlands and, when not caring for the ill or wounded in hospital, she went looking to help other Jews in Holland. In village after village, town after town, she could not find any. “The Jewish population was just destroyed,” she recalled.

The few people she did encounter had lost all their loved ones—children snatched away, parents rounded up and never seen again, entire families taken to death camps, save for one survivor. Of 120,000 Jews in the Netherlands, only 16,000 survived the Nazi Holocaust.

190

Citizens of Eindhoven killed on Sept. 19, 1944

The Canadians issued threats of harsh reprisal if the Germans allowed more mass starvation.

By late April 1945, with the Nazi regime in its death throes, talks started between the Canadians and the Germans—both aware that food stocks were almost completely depleted in western Holland. The Canadians issued threats of harsh reprisal if the Germans allowed more mass starvation, and an informal truce was hammered out to allow food to be rushed to desperate communities.

This was part of a larger Allied relief effort code-named Operation Manna, with airdrops of food to isolated Dutch communities starting on April 29. A few days later, truck convoys carried more food, while bombers—including RCAF—flew over the countryside, with airmen shoving food parcels through open bomb-bay doors. It was nerve-racking to fly low over German anti-aircraft guns, but more than a few airmen felt thrilled to see Dutch signs and messages laid out in farmers’ fields and painted on rooftops: “Thank You, Canadians!” Many of the Dutch were in dire health, despite their excitement over the food shipments.

“I think the condition of the people really hit most of us,” recalled Rifleman John Drummond, who was stunned by painfully thin men, women and children he encountered. “The farther west you went, the more starvation there was. We would see hundreds of civilians with just the clothes they have on.”

Many Canadians chose to go hungry and share everything they had with the scarecrow-thin Dutch. Joe Menchini of the Governor General’s Foot Guards gathered chocolate bars from his comrades and went with a friend to a local orphanage. Emaciated kids trembled with anticipation as they waited in line “Their hands were just shaking,” Menchini recalled.

His chum burst into tears at the sight of the children and had to leave, but Menchini, with tears in his eyes, continued to hand out the treats. For many Dutch, chocolate was liberation incarnate.

The Canadians pushed on, liberating village after town. With the food delivery and the mass of enemy surrenders, the fighting men put more stock in rumours the war was winding down.

But there was a growing fear in the ranks: no one wanted to be the last man to die in a long and terrible war. It gnawed away at those in the field and, as Major Gordon Brown of the Regina Rifles recalled, “made everyone keep just a little lower in his slit trench, just a little more cautious. For a combatant to think they might ‘get it’ when the war was ending—after coming through the several assorted hells for months on end—is a feeling worse than fear.”

On April 30, Adolf Hitler shot himself in the head. The man most responsible for the war that killed 60 million had escaped justice, but would live on in history as evil incarnate.

North Nova Scotia Highlanders advance to Zutphen, Netherlands, on April 8.

No one wanted to be the last man to die in a long and terrible war.

With the Fuehrer’s death, Germany began the process of surrendering. The Allies had declared it would be an unconditional surrender, and the German high command knew there would be no negotiating.

German capitulations started in Italy on May 2. In Europe, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, who was handed the poisoned chalice after Hitler’s death, began discussion with the Allies on May 4. They went on for several days, even as thousands more soldiers and civilians died from disease, starvation and direct attack.

The war ended on May 7. The Allies decided to hold formal celebrations the next day. May 8 would forever be known as VE-Day, for Victory in Europe. It was also a day when the oppressed and brutalized people of western Europe had their freedom returned by the liberators.

APREWAR OFFICER, Charles Foulkes started the Second World War as a major and was viewed as a good trainer of men. However, his rapid climb to major-general and command of the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division had been fraught with disappointment. In his first major battle, Foulkes had been a timid, even weak commander, overseeing the disastrous attack at Verrières Ridge in late July 1944. He should have been sacked, but Simonds protected his subordinate.

When Lieutenant-General E.L.M. Burns was fired as corps commander in Italy, Foulkes was sent to that theatre. It was felt, perhaps, he would do less harm there. But he surprised all by taking charge. While never popular, he proved a keen administrator. He returned to Northwest Europe as corps commander, and led I Corps in the final campaign to liberate the Dutch.

Wehrmacht General Johannes Blaskowitz (second from right) agreed to the terms set out by Foulkes (at left) in Wageningen, but no typewriter could be found. The surrender was delayed a day until the documents could be typed.

Foulkes negotiated the German surrender at the Hotel de Wereld in Wageningen, Netherlands. When the Germans tried to strengthen their hand by suggesting they might blow more dikes and flood farmland, Foulkes told them it would be a war crime and, he noted menacingly, those responsible would face a harsh justice. The Germans folded and signed the surrender document on May 5.

In a surprise twist, Crerar recommended 42-year-old Foulkes as Chief of the General Staff for the postwar army, choosing him over Simonds. Simonds was undeniably a better battlefield commander, but Crerar was evening some old scores.

But it wasn’t only vengeance. Crerar was a good judge of character: Simonds was a firebrand, while Foulkes was more diplomatic. To the surprise of most Allied generals, the government accepted Crerar’s recommendation. Montgomery felt Simonds’ treatment “was almost cruel.”

Foulkes proved himself the right leader in creating the postwar army. He was a critical conduit between the army, the politicians and the mandarins at External Affairs. He was appointed Chairman of the Chiefs of Staff Committee in 1951, overseeing the entire Canadian military until 1960. His replacement as Chief of the General Staff was Simonds.