Image credits: Provincial Archives of Alberta

part one

unlocking the scheldt

ANTWERP WAS THE KEY to shortening the war against the Germans. The Allies—from politicians and generals planning the attack to privates humping their way eastward through Normandy—hoped the German forces in full retreat might raise the white flag of surrender.

From late August to mid-September 1944, the Allied land armies, advancing on many fronts, crushed German opposition. But Hitler and his generals understood that denying Antwerp to the Allies was essential to holding off the onslaught.

The great Belgian coastal city is a deep-water port on the Scheldt River, some 80 kilometres upriver from the North Sea. British armoured units had moved with great élan to capture the city on Sept. 4, with significant help from Belgian Resistance fighters who battled against the Germans attempting to blow up the all-important docks. Captured largely intact, the docks to the second largest port in Northwest Europe could accommodate 1,000 merchant ships and move 40,000 tonnes a day. Taking Antwerp was a significant victory, but the supply line was still blocked because the Germans continued to hold the estuarial mouth of the Scheldt.

Map

the scheldt

COMMANDED BY CANADIAN General Harry Crerar, the First Canadian Army was comprised of II Canadian Corps, I British Corps and the 1st Polish Armoured Division. American, Belgian and Dutch soldiers also fought alongside the Canadians. The largest army ever commanded by a Canadian, its overall strength ranged from 200,000 to 470,000 soldiers, including 105,000 to 175,000 Canadians. Flooded, muddy terrain and well-fortified German defences made the Battle of the Scheldt especially gruelling and bloody. Some historians consider it the war’s most difficult battlefield. The five-week offensive brought the victorious First Canadian Army 41,043 prisoners, at a cost of 12,873 casualties, 6,367 of them Canadian.

View the map

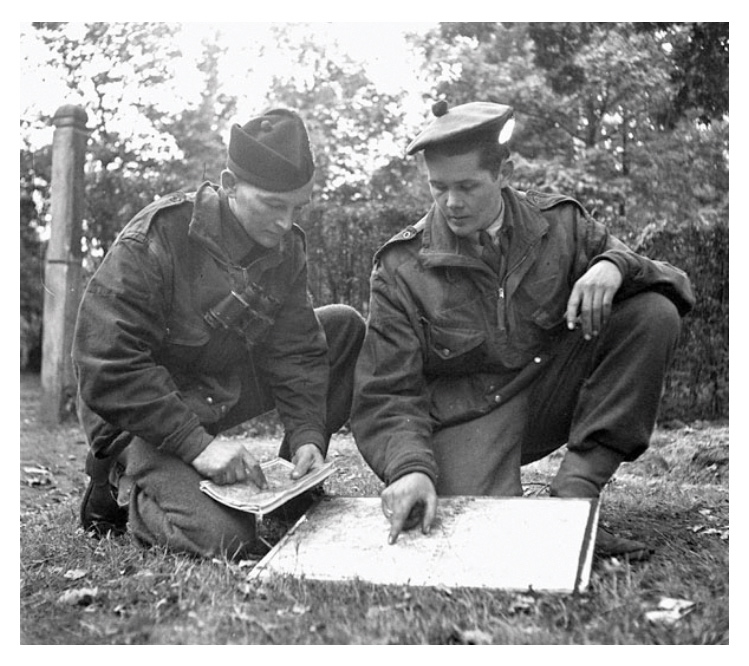

Montgomery walks with Crerar and Canadian Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds, who directed four major attacks in five weeks during the Normandy campaign.

Montgomery ordered the Canadians to open the waterway to Antwerp. The Germans had about 100,000 soldiers in the Scheldt, and the estuary was heavily defended with more than 750 guns and some 6,000 vehicles.

On the south bank of the Scheldt, a fortified zone of German resistance called the Breskens Pocket blocked vessels from steaming in from the North Sea, while the South Beveland Peninsula protected the island of Walcheren, which itself was a fortress that would deny shipping. All were defended fiercely by German units largely unscathed in battle, and all had to fall before supply vessels could reach Antwerp.

The German commander issued an order on Oct. 7 that the defence of the Scheldt was “decisive for the further conduct of the war.” If the Scheldt fell, “the English would finally be in a position to land great masses of material in a large and completely protected harbour. With this material, they might deliver a deathblow.” The defenders were to hold out at all costs.

Crerar had missed much of the Normandy battle, because First Canadian Army was not activated until July 23. Simonds, meanwhile, had been commander of II Canadian Corps since January, and the Corps had seen combat in Northwest Europe from the beginning of July.

2,463

Number of Canadian conscripts serving at the front

314

Number of Canadian conscripts killed, captured or wounded

Simonds was ruthless and willing to take casualties to achieve objectives. He also had a keen mind for battle. Among his greatest innovations were the ideas of transporting infantry in armoured vehicles and using bombers to smash dug-in defenders.

Crerar led the Canadians in clearing the coastal bases through August and September, but on Sept. 27 he was rushed to hospital, afflicted with persistent dysentery. The Battle of the Scheldt fell to Simonds. It would be his greatest campaign.

Simonds ordered the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division—commanded by Major-General Dan Spry and supported by units of the 4th Canadian Armoured Division and the British 51st Division—to drive the enemy out of the Breskens Pocket, a battlefield measuring 15 by 35 kilometres and cut through by the Leopold Canal. The area was defended by elements of Germany’s 15th Army—primarily the 64th Division. They were dug in, prepared and well-armed. But their best defence was the flooded farmers’ fields intersected by ditches, canals and raised dikes. This raised checkerboard terrain forced the Canadians to expose themselves whenever advancing.

The 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, commanded by Maj.-Gen. Charles Foulkes, would support the right flank, driving northeastward to overrun South Beveland before turning westward to attack Walcheren Island. The rest of 4th Armoured Division was on its right, although the infantry and armoured units would face fewer concentrations of enemy troops than the other two divisions.

The military unveils a British flamethrower at Camp Borden in England on Oct. 5, 1944. It was used by Canadians on the march to Germany.

It was fight or die —there was nowhere to retreat.

In the Breskens Pocket, the 3rd Division’s 7th Brigade was to assault northward across the Leopold Canal to engage the enemy and draw in reserves, while an amphibious operation by the 9th Brigade a few days later would hopefully catch the enemy by surprise, with his counterattacking forces already committed to battle.

The unhappy task of a frontal assault fell to the Regina Rifles—nicknamed “The Johns” (a wink to the fact that many had been farmers, i.e. Farmer Johns)—and the Canadian Scottish Regiment on the right, both of which had landed on June 6, 1944—D-Day—and fought almost continuously since then.

These spearhead forces were to cross the 30-metre Leopold Canal before striking northward. Water crossings were always dangerous as they separated the lead units from their support. The infantry girded themselves for battle. A surprise operation might buy some precious time, and so instead of pounding the enemy’s forward defences with artillery fire, the preliminary bombardment was held off to avoid alerting the Germans, even though their gunners were at the ready.

The defenders were to hold out at all costs.

Private Bill McConnell of London, Ont. prepares to toss a grenade during the advance in the Netherlands.

Instead, 27 Wasps—Universal Carrier variants equipped with Ronson flamethrowers that projected jellied napalm-like fuel—were used to burn the defenders out along the north bank. The jets of fire struck at dawn on Oct. 6, and the surprised German defenders died or ran for cover.

Following the flames, assault companies crossed the canal in canvas boats as the far bank burned. Most made it unharmed, although one boat carrying men from the Royal Montreal Regiment attached to the Reginas was badly cut up by enfilade fire. Along with the Scottish and platoons of the Winnipeg Rifles, the Johns did not get far beyond the canal before the enemy hurled themselves at the exposed Canadian position.

A week of battle ensued. It was brutal warfare, with both sides attacking and counterattacking, raiding and probing, night and day. The Germans came at the dug-in Canadians with bombs and bullets, and only a massive artillery screen by Canadian gunners aided the desperate infantry in holding off the frenzied assaults. It was fight or die—there was nowhere to retreat.

The German mortars and snipers took a toll. The Canadians dug in deep, burrowing into the soft earth, becoming one with the mud. Hot food was difficult to bring forward, and when it came it was from men slithering through cold muck, braving the fire, aware that it was crucial in keeping up the spirits of the fighting men. Liberally distributed rum was, as one Canadian called it, a “lifesaver!” Under a storm of steel, the soldiers’ best friend was the sharp-nosed spade, and the men dug while lying prone. The Canadians’ took a pounding at the canal but held on.

As Simonds had planned, the 7th Brigade’s grim battle was drawing in the enemy’s reserves, leaving the flank open for the amphibious attack by the 9th Brigade on Oct. 9.

Chugging along in painfully slow Buffalo tracked landing vehicles, which could carry up to 30 men but suffered from a shrieking airplane engine that alerted all within hearing distance to its arrival, the North Nova Scotia Regiment and the Highland Light Infantry landed after an agonizing seven-kilometre run-in. They were expecting to be discovered by the Germans the whole time, a water-borne force sunk in metal coffins.

They landed behind a smoke and artillery barrage, stabbing into the German innards. After an initial advance of some 1,500 metres, the enemy realized the Canadians had come in through the side door and turned to meet them. The Canadian spearhead clawed its way toward Hoofdplaat, which fell to them, and follow-on units pressed inland behind them.

The flooded farmland along the front was “utterly flat between dozens of intersecting dikes,” wrote Canadian infantryman Donald Pearce of the North Nova Scotia Regiment. “The dikes are about 20 feet high…and maybe 40 feet wide…. We scramble over them, or drive on top of them; they are bad to fight over, but merciful to hide behind.” With shells and mortar bombs crashing down, there were dead farm animals all along the front, swollen and reeking.

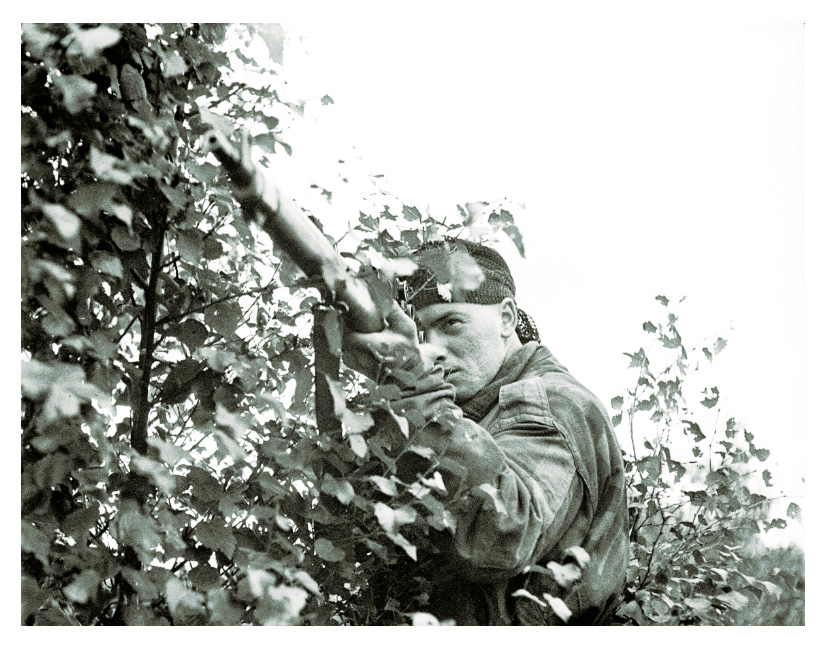

Corporal B.B. Arnold, a scout with the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, sites his rifle near Fort van Brasschaat, Belgium, on Oct. 9, 1944.

27

Number of Wasps used to burn out defenders on the north bank of the Leopold Canal

Most days saw Canadian sections working their way forward through the quagmire, supported by large-scale assaults against fortified positions with artillery, Vickers machine guns and anti-tank guns. There was no single, decisive battle in the grinding warfare. Instead, it was engagement after engagement, along a fluid front. This “devil’s dream of mud and dikes and rain,” as one Canadian called it, was an unending nightmare.

Advancing and employing fire-and-movement tactics, the Canadians took positions, and then waited for the enemy attack. And while these German assaults were often frightful and led to hand-to-hand combat, one Canuck remarked, “It is always easier to kill a rat out of his hole than in it.”

300

metres

DISTANCE OVER OPEN GROUND COVERED BY PRIVATE GORDON CROZIER with Bren gun and ammunition in hand—before he dug in and knocked out four machine-gun nests

27

Days in the Battle of the Scheldt

The Canadians fought forward, usually in sections of eight to 10 infantrymen, relying on each other for survival. Communication was sporadic at best, and often sections and platoons were cut off from battalion headquarters for days. Some sections were wiped out in ambushes; others were blown apart as they crossed minefields now covered in water. In every skirmish and assault, there were fewer and fewer men. In the cold and wet, somehow the Canadians found the endurance to keep going.

Lieutenant Blake Oulton of the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment spoke of the terrible losses to his 37-man platoon. After a series of intense battles, he said, “I wound up with 10 men, all told, in my platoon. How did we accomplish so much with so few men? I do think that the tough fibres of the Canadian soldier carried him through the most difficult operation of the whole war, which combined the worst weather and the worst fighting ground imaginable.” Those “tough fibres” also included a honed attack doctrine that emerged from the trials of Normandy.

As the Stormont, Dundas and Glengarry Highlanders were advancing on Roodenhoek, about four kilometres inland from the coast, on Oct. 15, No. 12 Platoon was taking heavy fire from snipers, machine guns and four 20-millimetre guns. The Glens had gone to ground and were inching forward in the muck when Private Gordon Crozier told his section to lay down fire. With a Bren gun in hand and nine magazines, he jumped up and dashed some 300 metres over open ground to the flank. The Germans turned their guns on him and he passed through a hail of bullets. One hit him, but he kept going, eventually manoeuvring to dig in along a muddy embankment that gave him a firing position into the four enemy guns. Crozier discharged short bursts of machine-gun fire, eventually knocking out all four. The redoubtable private kept fighting and was wounded two more times before being sent to the rear to receive medical aid.

As the infantry scrambled through the mud, they were helped by Allied fighter planes and Typhoons above the battlefield, raking enemy positions, knocking out strongpoints and providing much-needed moral support to the floundering soldiers. In return, the great German guns positioned across the Scheldt on Walcheren Island hurled massive shells into the Canadian lines. Hammered from the front, flank and rear, sometimes the only thing to do was to keep moving.

Toward the end of the campaign, the personal hygiene among the Canadians was ghastly. The stench of body odour was indescribable from the constantly wet men in sodden khaki uniforms crawling with lice. Impressive, too, was the animal-like sense that developed among the soldiers struggling in the slime. Their muscle memory reacted faster than their brains as they dove for cover when shells dropped or machine-gun fire opened up. Living in filth, the Canadians kept pushing, past the dead and dying, the rubbled farms and the unspeakable sights. Despite the strain, “what we’re fighting for is always clear in our minds,” wrote Captain Hal MacDonald of the North Shore Regiment to his wife as the end of the battle neared.

German resistance finally broke and they surrendered on Nov. 3. The battle for the Breskens Pocket cost some 2,077 Canadian casualties, but it cleared the south bank of defenders, while annihilating the entire German garrison. But the Battle of the Scheldt was not over, with the 2nd Division still fighting an obstinate enemy.

They landed behind a smoke and artillery barrage, stabbing into the German innards.

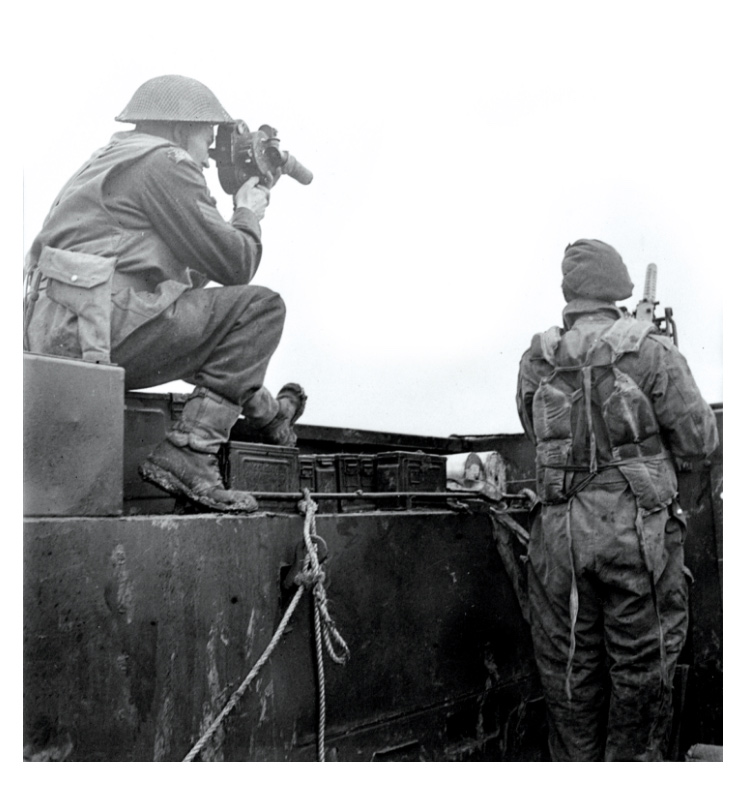

Carriers are mired in flooded ground west of Breskens, near the Belgium-Netherlands border, on Oct. 28.

This “devil’s dream of mud and dikes and rain” was an unending nightmare.

525

square kilometres

Area of the Breskens Pocket battlefield, cut through by the 30-metre-wide Leopold Canal

EAST OF THE Breskens Pocket, the 2nd Division had fought northward from Antwerp, with the 4th Armoured Division on its right flank, since Oct. 2. Pushing over the Albert Canal, the Canadians cleared the Germans from Antwerp’s northern suburbs and then advanced some 40 kilometres until they ran into a fortified enemy position at Woensdrecht. A 2,500-man fighting group of elite paratroopers blocked the Canadians from turning west toward Walcheren Island.

The area around Woensdrecht had flat, muddy approaches, cut by tall dikes, most of them four metres or higher, and then low-lying water. The main body of paratroopers were dug in along a dominating ridge on the edge of Woensdrecht, but enemy fire came from several directions: snipers were situated on the forward slope of the dikes to fire at advancing troops, while others were on the reverse slope to avoid shellfire and catch men exposed as they came over the tall dikes.

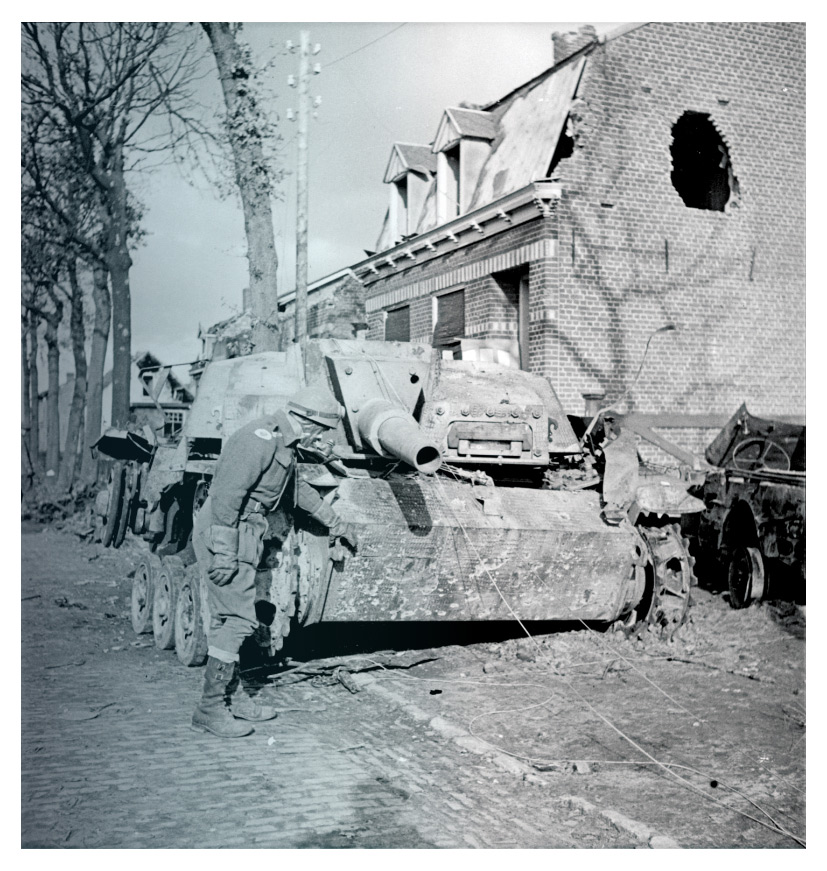

The Canadians made contact with the enemy on Oct. 6. On that first day of battle, the Royal Canadian Regiment was handled roughly by the paratroopers, while the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada also ran into a buzz saw of enemy fire. At one point in the battle, a German self-propelled artillery piece, armed with an 88-millimetre gun, slashed its way into the centre of the Black Watch position before it was knocked out.

The Calgary Highlanders laid into the enemy on Oct. 7, and the Germans fought just as hard. The two sides raged back and forth for three days, with tanks and artillery adding to the carnage.

After a week of battle, the Black Watch launched another attack on Friday, Oct. 13. The regiment had been shattered at Verrières Ridge on July 25 and now they were torn apart again, after advancing some 1,200 metres over saturated beet fields into enemy fire. All the company commanders were killed or wounded, with 145 total casualties. Marking the tremendous courage and the terrible losses, the date would be known forever in the regiment as Black Friday.

Three days later, at 3:30 a.m. on Oct. 16, the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry followed a heavy artillery barrage through the enemy lines. In ferocious night fighting, the Germans struck back, supported by tanks and artillery.

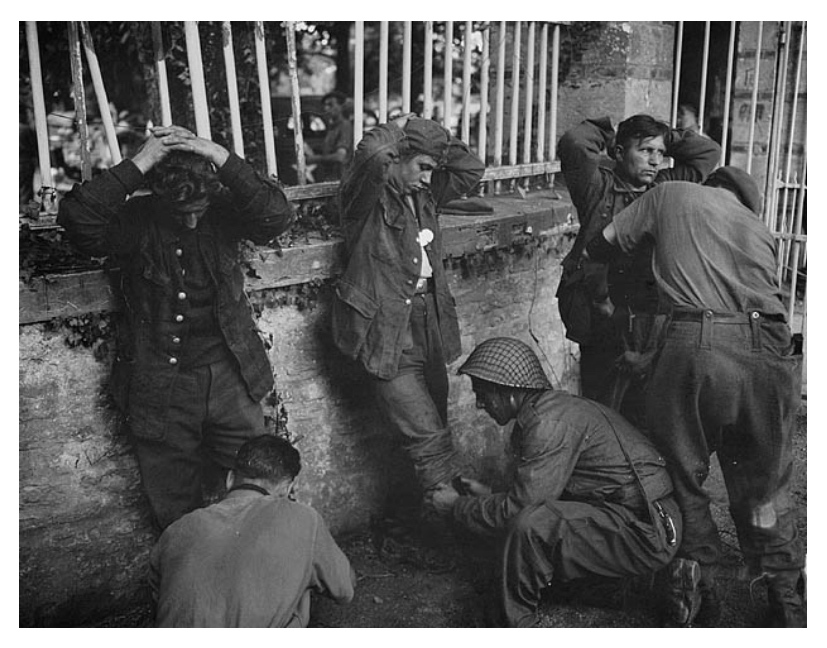

Corporal S. Kormendy and Sergeant H.A. Marshall of the Calgary Highlanders clean and adjust their sights during an October 1944 scouting, stalking and sniping course in Belgium.

The Rileys were in danger of being overrun when Major Joe Pigott called desperately for artillery fire on

his company’s position. More than 4,000 shells smashed down, catching the Germans above ground as the Canadians stayed low in slit trenches. The regiment reported that “the slaughter was terrific.”

There was another week of battle, but the Germans were finally defeated on Oct. 24. Too few Canadians had been ordered to do too much. And still the cut-up 2nd Division limped on, moving westward in late October through the narrowing terrain leading to South Beveland and the final phase of the operation, the capture of Walcheren. Walcheren Island is below sea level and saucer-shaped, and at the time was connected to the mainland by a causeway one kilometre long and 40 metres wide. Even combat-hardened soldiers blanched at this defender’s dream: it seemed nothing short of a shooting gallery. A handful of machine guns could wipe out whatever force the Canadians threw at it.

Defending Walcheren was the 70th Infantry Division, a weak German formation derided as the Stomach Division, composed of men afflicted with all manner of illnesses and ulcers from the relentless warfare of the Eastern Front. But protected in concrete bunkers, they could defend like any others. The Canadians prepared for a frontal assault across the causeway, while the primary attack would be with amphibious landings by British commandos along the southern and western coast of Walcheren.

1 kilometre

Length of causeway leading to Walcheren Island

Simonds had considered the problem of how to force the Germans into surrender on Walcheren Island and landed on a radical plan to use Allied bombers to shatter the dikes and flood the island. The Dutch were horrified at the thought of sea water ruining their reclaimed farmland, but Simonds knew that swamping the terrain would leave the German garrisons isolated and more likely to surrender.

He went to Britain to convince the air marshals of the plan. It was well known in the army that the bomber barons did not want to divert resources from smashing German cities, oil factories and infrastructure to support land operations. Simonds succeeded in convincing them. On Oct. 3, the bombers carried out their work, dropping 10,000 tonnes of bombs and breaching a series of dikes near Westkapelle. The sea stormed in and deluged much of the island.

With the main assault to come from the British amphibious landings, the Canadians again had the role of drawing in enemy strength. Arriving from the east, the lead units of the 2nd Division searched for pathways across the mud flats below the kilometre-long causeway, but they couldn’t locate firm enough ground for masses of men and vehicles. They gritted their teeth and faced the killing ground. The Black Watch, already ragged and shot through from its losses at Woensdrecht, was first to assault. A single company hoped to strike hard and fast, and the men set off in a freezing rain at mid-afternoon on Oct. 31. Supporting artillery turned the causeway into a furnace, but enough Germans survived to stop the attack with rifle and machine-gun fire. There was even a tank dug in and hurling armour-piercing shells down the causeway that ricocheted along its narrow confines. During several hours of battle, much of the company was destroyed. Ten were killed and 34 wounded.

100,000

German troops defending the Scheldt Estuary

10,000

Tonnes of Allied bombs used to breach dikes and deluge much of Walcheren Island

That night, Halloween evening, the Calgary Highlanders tried to breach the enemy line at the end of the causeway, again supported by shells and smoke. They also suffered crippling losses in two brave but futile attempts, with the second at 6:05 a.m. on Nov. 1. Shrieking shells and dying men created an unholy cacophony, but the Calgarians held onto parts of the causeway by fortifying some of the large, still-smoking craters. Before dawn on Nov. 2, the Régiment de Maisonneuve bravely drove forward behind a smashing artillery bombardment that finally hurled the Germans back. They

held a precarious position about 460 metres onto Walcheren. “I have no words to describe the hell,” said Lieut. Charles Forbes, who was wounded in the fighting but stayed in command of his steadily dwindling group. The enemy rained down mortar bombs and more men died in the extraordinary violence. The Maisonneuves were forced to withdraw across the causeway.

Exhausted, scruffy and red-eyed, the Canadians were eventually relieved and marched to the rear, unaware that British forces—infantry, commandos and naval crew—had landed on the island at Vlissingen, on the southern shore, and at Westkapelle, at the western tip, on Nov. 1.

Members of the 1st Rocket Battery, Royal Canadian Artillery, load a rocket launcher at Helchteren, Belgium, on Oct. 29, 1944.

The shriek of shells and dying men created an unholy cacophony.

These three snipers of the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada killed 101 enemy between D-Day and Oct. 9, 1944.

The futile Canadian assault along the causeway did not distract the Germans, but Simonds’ flooding of the island reduced their ability to defend. After sustained battles and tremendous sacrifice, especially at Westkapelle, where Royal Navy warships drew fire onto themselves from shore batteries to give time for the landing force to go ashore, a mass of Germans surrendered on Nov. 8. First Canadian Army captured 41,000 prisoners in the victory.

“It has been a fine performance, and one that could have been carried out only by first-class troops,” Montgomery said of the Canadians.

It was generous praise, but even this was an understatement. While they suffered 6,367 casualties, the Canadians achieved a critical strategic victory. The Battle of the Scheldt—next to the D-Day landings—must be considered among the most significant Canadian contributions to the Allied victory in Europe.

ANTWERP ACCEPTED its first supply ships on Nov. 28, a relief to Eisenhower and every logistics officer in the Allied armies. The failure of Market Garden ensured the war would not end in 1944, but the opening of Antwerp by the Canadians enabled it to be won the next year. Yet there would be no victory before a series of battles and campaigns with more heavy losses, grim sacrifice and tremendous heroics.

Canadian soldiers dig a slit trench during Operation Spring, south of Ifs, France, on July 25, 1944.

THE relentless month of fighting for the Scheldt—from Oct. 2 to Nov. 8, 1944—slashed the Canadian fighting forces, with 6,367 casualties. The 3rd Division had 341 killed and more than 1,600 wounded. The 2nd Division lost even more soldiers, with some 2,600 killed and wounded. The remaining losses fell to other units. Some 600 soldiers in the 2nd and 3rd divisions were hospitalized with battle exhaustion. They had been pushed beyond physical and mental limits. After their evacuation from the front, these men were prescribed narcotics or other medicines to ensure they got 48 hours or longer of undisturbed sleep. Many recovered, but not all.

Continual exposure to strain and tension; watching comrades killed or maimed; the unyielding threat of death; hard living in cold, wet conditions—these stresses pushed all men to the brink.

Lance-Bombardier Bert Field wrote in a letter home of the “sick desperation” that built in him after the slog through the polders, the low-lying land reclaimed from the sea. “It’s not the physical hardships of this war that are going to leave their mark on us,” he wrote, “It’s that continual battle that goes on inside each one of us.”

There was a manpower shortage even before the Battle of the Scheldt, but the wasting combat in the mud made it even worse. The Scheldt casualties weakened the infantry regiments that bore the brunt of the fighting, suffering around 75 percent of all losses.

News circulated back to Canada that the infantry units were low in strength and suffering unnecessary casualties because of it. Too few men were asked to do too much, and too often. Minister of National Defence J.L. Ralston went overseas to investigate. A veteran of the Great War and a champion of those in service, he returned to Ottawa by mid-October, shaken and determined to stand up for those in combat. He demanded that Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King enact conscription.

King was horrified at the request since he had spent much of the war ensuring that there would be no repeat of the conscription crisis of the Great War, which had been devastating to Canadian unity. The prime minister struggled to find a compromise, even though there were already close to 60,000 trained infantrymen in Canada who had been conscripted for home defence since June 1940. But they refused to go overseas voluntarily and King would not force them. There was no solution and as his cabinet was tearing itself apart, King fired Ralston on Nov. 1, 1944, to the shock of the country.

His replacement, former First Canadian Army commander Andrew McNaughton, also failed to convince the conscripts in Canada to volunteer. The King government almost collapsed over the issue, but eventually the slippery prime minister reversed himself.

On Nov. 22, King ordered a contingent of 16,000 infantry-trained home defence draftees to be sent to Europe. Some 13,000 went overseas, with 2,463 serving at the front, where 314 were killed, captured or wounded. By most accounts, they fought well and within a few weeks at the front, they were usually accepted as equals within the ranks. The Canadians in the field needed every man they could get for the coming battles.

6,367

canadian casualties in the Battle of the Scheldt

12,873

Allied casualties in the Battle of the Scheldt