Image credits: Capt. Alexander M. Stirton/DND/LAC/4233505

conclusion

bonds forged in blood

TODAY IS VE-Day and I should be happy, but I find it very hard because so many of my comrades who should have been here are lost and will not return to their loved ones,” wrote Private Gerald Vincent Montague of the Canadian Scottish in a letter to his wife and daughter on May 8, 1945. Like most Canadian troops, he had endured months of battle in the Northwest Europe campaign. So many Canadians like Montague had written off their lives to keep going forward. And now they had survived. There were wild parties in Canada, Britain and across the western Allied world, but the soldiers in the field were more subdued.

“There was little celebration,” recounted Captain Malcolm Sullivan, who fought with the 11th Canadian Armoured Regiment in Italy and the Netherlands, “but a strong feeling of satisfaction of having finished a good job and prevailed.”

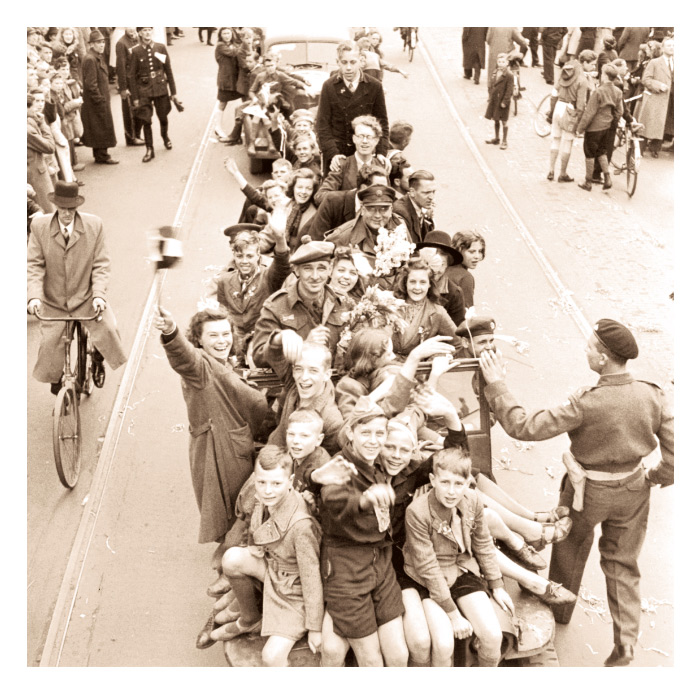

However, the Dutch were ecstatic. They had their country back, their freedom and their lives returned to them. While the American, British, Polish and other Allied forces had all fought for them, it was the Canadians who were most identified with the liberation.

Tens of thousands of Canadian soldiers in Europe were moved to the Netherlands after the May 1945 victory. They and their hosts faced a glorious summer together. Amid celebrations, parades and good cheer, the Dutch opened their homes to the Canadians and strong friendships were made.

1,118

Number of Commonwealth burials at Bergen-op-Zoom Canadian War Cemetery

1,886

Number of Dutch women who became Canadian war brides

Dutch women in sailor suits (above) accompany victorious Canadian soldiers in post-liberation Amsterdam in June 1945.

“They treated us so well,” said Canadian nurse Honora Greatorex. “They didn’t have much to give, but they seemed to give it all.” The Canadians in turn went out of their way to help rebuild the country.

The 260,000 Dutch men snatched by the Germans for slave labour began to return to their communities, having suffered terribly from the ordeals of forced evacuation and pitiless work. Thousands had died in horrendous conditions, and those who survived were gaunt and withered, wearing rags and suffering from bleeding sores. It didn’t help when they returned to their towns and villages to find the strong, relatively rich liberators making friends with the local girls.

It may not have been fair, but the young Canadians were not mindful of hurt feelings and neither were most of the Dutch women who befriended the liberators. There were walks, dances and adventure as Canadian men and Dutch women struck up friendships and sparked romances.

Their “English voices sounded melodious to our ears,” said Reina Amsterdam, as she recalled the charged atmosphere that summer. “Dressed in smart uniforms, their strength and power radiated from them like an overwhelming perfume. These were our heroes. We loved them, admired them, and longed to feel part of them; to hear their songs and listen to their stories of battle and victory.”

Many relationships formed through the summer, although not all the Canadians were saints. For some, it was rapid romance and heady lust; but there were long-term relationships and at least 1,886 marriages. Many of these women eventually travelled to Canada to start a new life, the crest of a wave of Dutch emigrants to the country that had produced the soldiers who returned their freedom.

It had been a glorious summer, but by late fall, even the liberators were growing tiresome. “It was time to go. We had grown slack and we were wearing out our welcome,” said Major John Gray, who served in the Intelligence Corps. Fortunately, the problem took care of itself as the Canadians returned home to their loved ones. Most were gone by early 1946.

The Dutch opened their homes to the Canadians and strong friendships were made.

More than 7,600 Canadians died fighting in the Netherlands, and at least 5,700 are buried with comrades in cemeteries or commemorated on memorials at Groesbeek, Adegen, Bergen op Zoom and Holten. Many Dutch adopted Canadian graves, and to this day, schoolchildren lay flowers in powerful acts honouring the liberators and refusing to let the sacrifice be forgotten.

Some 200,000 Dutch emigrated to Canada from the war’s end to the late 1970s. War brides and others became living reminders of the war, keeping the memories alive and strengthening the bond with the Dutch in Europe.

The powerful history of the liberation was also marked in 1946 with the Netherlands’ first gift to Canada of 20,000 tulips, some of which were immediately planted at the Civic Hospital in Ottawa, where Princess Juliana of the exiled Dutch royal family had given birth to Princess Margriet in 1943. Canada had ensured the hospital ward was declared extraterritorial so the princess could be born a Dutch citizen. The gifts of tulips continued and in 1953, Ottawa’s Tulip Festival was established, a living memorial linking the liberators and the liberated.

Canadian men and Dutch women struck up friendships and sparked romances.

Seventy-five years later, most of the Canadian veterans with first-hand memories of the liberation have passed away. So, too, have most of the Dutch who experienced the Hunger Winter and the liberation.

Canada and its soldiers played the most important role in giving the Netherlands back to the Dutch, even as they fought through terrible battles in the Scheldt and Germany. They defeated the Germans and saved Europeans from oppression and starvation. They were victors and liberators, but the cost was terribly high in Canadian lives. Their sacrifice and service will never be forgotten.

Displaying a captured Nazi flag, returning troops aboard the transport ship SS Pasteur arrive in port at Halifax.

More than

7,600

Number of Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen killed fighting in the Netherlands

More than

7,600

Number of Canadian soldiers, sailors and airmen killed fighting in the Netherlands