Image credits: PhotoQuest/Getty Images

part two

winter warfare

IN THE AFTERMATH of the costly victory at the Scheldt, the survivors were moved into reserve. The fought-out Canadians needed a period of rest and recuperation. In large cities and small villages, much of the Canadian Army was billeted among the Belgians and the Dutch. The Canadians were welcomed by both, but developed tremendous affection for the Dutch.

Hot food and occasional stiff drink added to the rejuvenation. Care packages from home caught up to some men, who cracked them open with delight, savouring treats, magazines and cigarettes. In return, soldiers tried to put pen to paper to share their experiences, or at least what they thought those at home might understand. With a 48-hour leave, soldiers raced off to Paris, Brussels and Antwerp. Young men fresh from a month of fighting packed in a lot of living.

In January 1945, Andy Anderson of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion moved with his unit to Berik, Netherlands, on the Maas River. He and his comrades were surprised at the warm welcome of the Dutch. They were, Anderson noted, “generous and welcoming to a fault…. They had been punished pretty badly by the Germans. We opened their bakeries, got the electricity going, and generally helped get the cities and villages working again.”

While the liberated Dutch were grateful, they also let it be known that much of their country remained under German occupation.

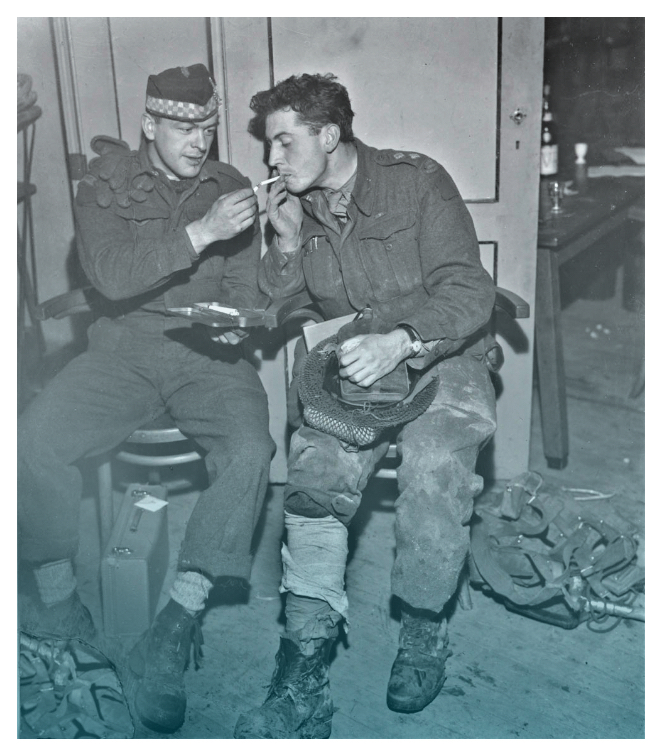

Both wounded on the causeway to Walcheren Island, Private D. Tillick of the Toronto Scottish Regiment and Lieutenant T.L. Hoy of the Calgary Highlanders wait for treatment.

Young men fresh from a month of killing packed in a lot of living.

After more than four years of occupation, the nine million Dutch were suffering terribly. As in other western European countries overrun early in the war, the Germans had executed members of the civil and military elite, installed their own military leaders, co-opted some of the population to act as secret police to carry out their vicious policies, and steadily pillaged the country of almost everything that could be stolen.

The treasury was robbed, the monarchy’s estates fleeced, factories dismembered and sent to Germany—including, one postwar report noted, some 13,786 metalworking machines—and about two-thirds of all

cars and buses were driven away. Even the beloved Dutch bicycles were not safe, with two million pinched of four million in the country.

The plight of the Dutch had become harder and harder as Germany suffered under aerial bombardment and shortages of war materiel, which forced the occupying force to find new ways to strip the Netherlands bare. But the invasion of June 1944 had brought much hope of a rapid liberation.

By September, the Dutch government and monarchy in exile had been swept up in the audacious Operation Market Garden, feeling it was the beginning of the end. From Britain, they sent word that the Dutch Resistance should assist the Allies and that the rail workers should abandon their posts. Dutch flags and the historic colours of orange were broken out, and many of the Dutch Nazi sympathizers fled in terror of retribution.

But when Market Garden proved a bridge too far, the Dutch were left exposed. Through the Gestapo and the hated ‘Greens’—internal police filled with Dutch turncoats—the Nazis struck back, crushing the resistance and carrying out terror attacks. Using hunger as a weapon, they also curtailed food.

Everyone was victimized, but Jews were singled out for the worst treatment. From early in the war, the 120,000 Dutch Jews had been targeted. They were forced from their jobs, then ordered to wear a yellow Star of David, ghettoized, and as the death camps became operational, sent to their doom.

Able-bodied men were increasingly rounded up for slave labour, with some 260,000 eventually dragged away from their communities. They were transported to Germany or other sites in Europe and made to work in dreadful conditions, always with the threat of execution for those who disobeyed. Perhaps as many as 300,000 men and women went into hiding. The Dutch called it “diving,” and they scattered across the country, into remote areas, hiding in every attic, basement or abandoned site they could find.

Dutch Jews board a train waiting to take them to a concentration camp. Seventy percent of the Dutch Jewish population died in the Holocaust.

The Dutch Resistance, which grew in strength during the war to about 76,000 people, tried to help with forged papers and occasionally striking back at their hated overlords, but the German method of retaliation was cruel and designed to sow terror. There were often mass executions of prisoners and public murders.

The village of Putten was singled out in one random terror attack, with 552 innocents executed or deported to death camps, while many other towns witnessed the shock of random murders—of those who picked up Resistance pamphlets off the ground and railway workers who were involved in the strikes.

“The weeks before us will be the most difficult in the existence of our nation,” said one of the announcers of Radio Oranje, the Resistance’s voice from Britain, after the failed Market Garden operation.

On the fighting fronts, the Germans had rebuked the Allied forces in Market Garden and fuel shortages had curtailed American advances along other fronts. At the same time, German V-1 and V-2 long-range ballistic missiles rained down on southern England until the rocket sites were overrun in October 1944. The attacks caused some 9,000 civilian and military deaths.

16,000

of 120,000

Number of Jews to survive German occupation of the Netherlands

300,000

Dutch citizens in hiding

These losses also forced the Allied high command to turn considerable resources to silence the remaining V-2 mobile units, which launched the 14-metre rockets fuelled by liquid ethanol and oxygen and equipped with a warhead of about 910 kilograms of explosives. However, the Allied advance drove the V-2s back, and soon their operators focused on Antwerp. Over the coming months, 6,000 missiles would kill or maim thousands of Belgian civilians and military personnel. As one Canadian gunner remarked of the rockets in a letter home: “When those things are flying around, everybody is in the front lines.”

With the cold weather in November, the front stagnated. Canadian units went back into the line along the Maas and Waal rivers. Winter warfare was new for those in Europe, and it demanded fortitude against the elements. The watch on the Maas was a miserable period for soldiers so far from home, but soon the Canadians scrounged materials from abandoned farms and created rough dugouts not dissimilar to those in which some of their fathers had lived on the Western Front in the previous war. With periodic artillery and mortar fire, the soldiers, gunners, troopers and engineers dug deep and found ways to make themselves small. Despite reduced intensity in fighting, there were steady night patrols and occasional raids.

The battle in the air remained active. The Royal Canadian Air Force flew sorties with the British and Americans, attacking tactical targets close to the front while bombers concentrated on the cities and infrastructure.

Allied airpower was steadily wearing down the enemy’s fighting effectiveness, and the Luftwaffe was much reduced. The Germans couldn’t protect everything—especially their vulnerable supply lines—and they continued to pull back anti-aircraft guns to defend their cities against the bombers. By the end of the war, about 900,000 men and boys were operating at least 19,713 anti-aircraft guns against the bomber threat, revealing the extent of the fear of the bombers. Had even a portion of these guns been stationed close to the front lines, the campaign into Germany would have been more costly.

When Market Garden proved a bridge too far , the Dutch were left exposed.

American troops inspect German V-1 rockets on April 15, 1945, near the Mittelbau-Dora concentration camp and under-ground rocket factory in Germany. Prisoners were forced to manufacture the weapons; more than 20,000 died.

265,000

Dutch men were used as slave labour

76,000

joined the dutch resistance

THE ALLIED FORCES were preparing a new series of offensives for early 1945. Trucks ran day and night from Antwerp, creating stockpiles of fuel, ammunition and food. Engineers built new roads and shored up those dissolving into mud from overuse. There were thousands of engineers and pioneers involved in the stunningly complex logistical work.

This frenzy of activity was abruptly disrupted when the Germans launched an armoured thrust in a surprise year-end offensive. Under cover of snow and fog, the 5th and 6th Panzer armies struck the Allies in the Ardennes on Dec. 16. Talk of the war ending in 1944 had died out after the bloody nose of Market Garden, but few anticipated that Hitler would so recklessly roll the dice in a last-ditch offensive.

The initial German strike was slowed by a resilient American defence in what became known as the Battle of the Bulge. After a month of fierce fighting, the Germans were ground down, losing precious armoured forces and consuming impossible-to-replace fuel.

While Canadian army forces were not engaged in any significant way, RCAF fighter squadrons supported the Americans, especially a week into the battle when the skies cleared and the enemy was ripe for an aerial assault. Luftwaffe high command threw everything it had into the operation, but Allied fighters tore them apart, with RCAF squadrons fighting alongside their American and British counterparts. In one incredible feat on Dec. 29, 1944, Flight Lieutenant Richard Audet, flying with 411 Squadron, RCAF, shot down five enemy planes in a day, instantly becoming an ace. It was Audet’s first engagement. The 22-year-old was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, but did not live to see the end of the war, killed by anti-aircraft fire on March 3, 1945, while strafing locomotives.

291

Number of Canadian casualties in the five-day see-saw battle for the island Kapelsche Veer on the Maas River

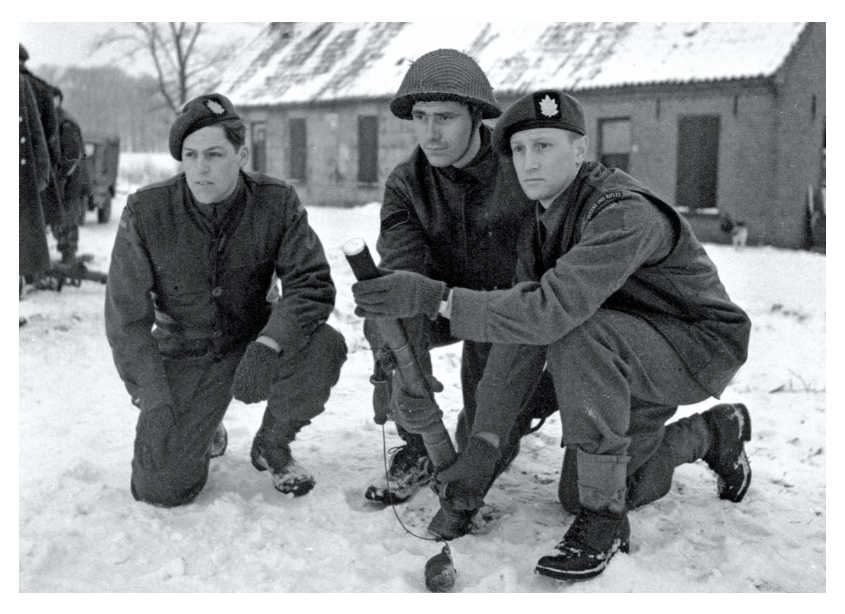

Canadian infantrymen earn their way around a two-inch mortar at the non-commissioned officers’ school in Ravenstein, Netherlands, on Jan. 26.

WHILE THE GERMAN ASSAULT was being blunted and then finally defeated at the end of January, the largest Canadian operation of the time was at Kapelsche Veer, a small, flat, treeless island in the Maas River. German paratroopers had a fortified position here jutting into the Allied lines and the Canadian command feared it would be used as a jumping-off point for raids.

Polish and British forces had tried three times to snuff it out and failed. Now, a large Canadian battle group would attack. The 4th Armoured Division’s war diarist wrote that it was proud “to have the distinction of being a pinch-hitter, but the pleasure, if not the distinction, is a dubious one.”

The Canadians did not want the dirty job, but the Lincoln and Welland Regiment, the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders of Canada, and the South Alberta Regiment were ready to strike. The attack went in on Jan. 26, supported by 300 artillery pieces and dense smoke-screens. But the German paratroopers were dug in deep, protected in a series of underground tunnels. The Canadians, wearing white hooded winter suits, were repelled with heavy losses by the tough paratroopers.

In the withering cold, the Canadians attacked again, advancing over the frozen bodies of comrades lying on the battlefield. “Men and parts of men, in muddy uniforms of grey, blue-grey and khaki…scattered across the face of the rising ground that had been fought for so bitterly and so long,” recounted one Argyll private.

A series of see-saw battles went on for five days before the paratroopers were driven to defeat. The fighting was “sheer misery,” said an official report by the 10th Brigade.

The weeks before us will be the most difficult in the existence of our nation.

The Germans lost 64 killed and 34 prisoners, with another 300 wounded from battle and frostbite. The victory was costly for Canada, with 291 casualties; the Lincs suffered most, with 89 killed and 143 wounded. One slain Argyll was Private Howard Wagner, whose mother Nora had already lost two sons in earlier fighting.

When those things are flying around, everybody is in the front lines.

THE ALLIES had been surprised by the Battle of the Bulge, and despite ending the German offensive, they were now worried about what the enemy might have in store next.

Even with intelligence breakthroughs, the Allies were not certain about what Hitler’s scientists were cooking up in their labs. The V-1 and V-2 rockets were evidence of German technological advances. Above the battlefield, the German Me-262 jet fighter was an utter shock to the Allies first encountering it in December 1944. While not many of the fighter jets were in service, if they rolled out of the factories in any significant number they could shift the balance in the air war.

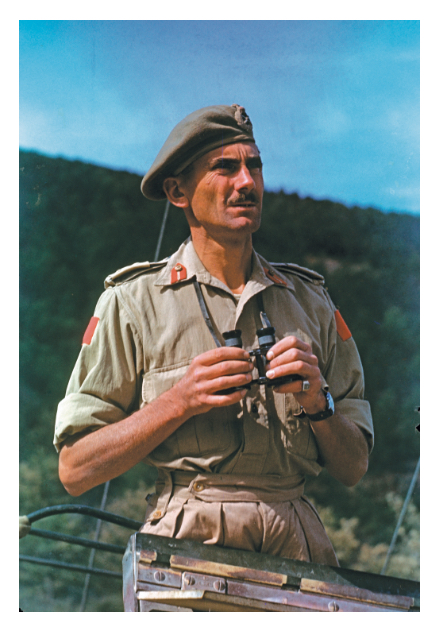

Sergeant Real Lalonde motions for ‘D’ Company, Régiment de Maisonneuve, to move forward in Cuyk, Netherlands, on Jan. 23, 1945.

The introduction of the Type XXI submarine late in the war caused fear of a new offensive against the convoys carrying essential supplies from North America. These were submarines designed to remain submerged, unlike previous U-boats which were surface ships that submerged for brief periods. None of these proved to be war-winning weapons, but together they showed that the Germans were still dangerous.

The Battle of the Bulge and the super weapons led the Allies to marshall themselves for the coming grand battles with much uncertainty. The bomber offensive against German infrastructure continued, and while some critics in hindsight would say it was overkill, there was the very real fear that the Germans might be readying for a new strike. The Allies planned to beat them to the punch.