Image credits: Lieut. Daniel Guravich/DND/LAC/PA-167199

part four

the final push

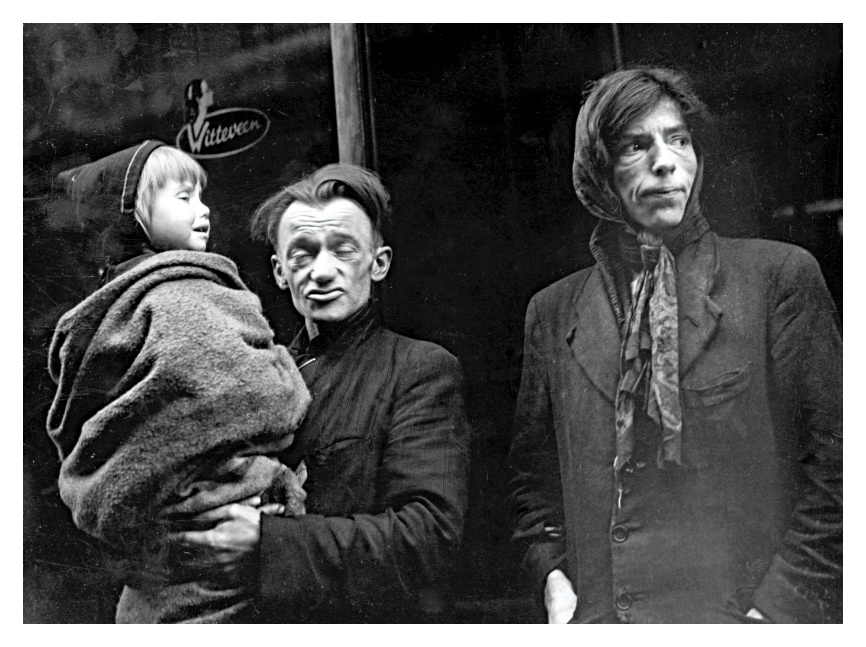

ALL EYES were on Germany, but behind the Allied advance were many tears of joy from

the liberated Dutch. From as far back as the Scheldt campaign in October 1944, the people were gradually being freed as fighting swept across their land. There had been painful prices to pay, including the flooding of Walcheren Island, but the Dutch had begun to rebuild their society in the liberated south of the country. Still, some 4.5 million citizens under German occupation in the north and west continued to suffer from dwindling food stocks.

The Germans had been systematically starving the Dutch since September 1944, removing food and reducing the official food rations to fewer than 750 calories a day. There was a “constant feeling of hunger,” one Dutch child remembered, “and eating had therefore become the high point of the day.”

With most of the crops and food stolen by the locust-like Germans, and with almost no electricity or gas, people in the cities relied heavily on the official ration. Over the next six months, it would be further reduced, eventually to about 350 calories. Healthy humans need about 2,000 calories a day. Germany was using food as a weapon to force submission through starvation.

Life in occupied territory is like life in a prison.

The weakened citizenry suffered in their unheated residences when winter hit. The

old died first; the young followed.

“Life in occupied territory is like life in a prison,” a Dutchman wrote in November 1944. “The guards can come into the cell whenever they want, there is no light and heating, and once a day you get a bit of food that is completely inadequate.” The food and fuel situation got even worse over that long, cold Hongerwinter (Hunger Winter).

As those in the cities starved, some took forlorn trips to the countryside to barter and beg for food from farmers. Famished citizens traded precious items—watches, silverware, anything of value. In return, they carried back small bags of potatoes, sugar beets or turnips. Not all returned home. Along the roads were corpses of those who had collapsed from their malnourished state.

“People with their feet torn, blood in their shoes,” Henry van der Zee remembered his father recounting. “Children not older than 10 and hardly clothed…. A young boy with a pushcart in which he had his younger brother, dead…. Two boys who had been going from farm to farm for months.”

Society began to break down as hunger and fuel shortages closed schools and businesses. Garbage was not collected. Hospitals had little medicine. Black markets emerged where some items and food were available at a high price. Family pets disappeared. Many people turned reluctantly to plentiful tulip bulbs to supplement their diets. The bulbs were slightly poisonous unless prepared properly and difficult for weakened people to digest.

“It is just too much to die on,” was a common complaint, “but certainly too little to keep you alive.”

After the Rhineland battles, Crerar’s army remained in the front lines waiting for the next assault. The Americans were driving the enemy back and Montgomery ordered an advance to the Rhine. There was little opposition left on the west bank, but the historic Rhine was large, wide and swollen. Along the east bank, the Germans would make a stand. Crerar received welcome news that I Canadian Corps would be sent from Italy for the final assault. In late August 1944, after the Allied victory at the Gothic Line—a 16-kilometre-deep defensive belt extending across Italy from coast to coast—the Germans had continued to skilfully retreat, using rivers and gorges as natural defences. The weather turned nasty in October, with the roads dissolving. Morale sank.

750

CALORIES PER DAY

Dutch food rations allotment in early 1945

350

CALORIES PER DAY

Dutch food rations allotment BEFORE liberation in April 1945

It is just too much to die on, but certainly too little to keep you alive.

Everyone could see that Northwest Europe was the main theatre of battle, and the bulk of supplies, vehicles and ammunition were being sent there. The Mediterranean front was reduced to trench warfare. In such conditions, the soldiers began to go absent without leave or engage in other acts of indiscipline. “The troops were about at their limit as an efficient fighting force,” one medical officer reported.

The soldiers in Italy had been sneeringly labelled D-Day Dodgers by some, but they could quite rightly boast that they had been fighting for almost a year prior to D-Day. Moreover, the Italian campaign had drawn down German resources, with about 23 divisions defending across hundreds of kilometres. Those troops might have been better used to shore up the Eastern Front and provide more counterattacking forces in the West.

Once shipping was secured, the Canadians made their way back from Italy to Europe, with the two corps united in First Canadian Army on April 1.

American GIs land on the east bank of the Rhine River.

I heard bullets going by and I looked up and my chute was full of holes.

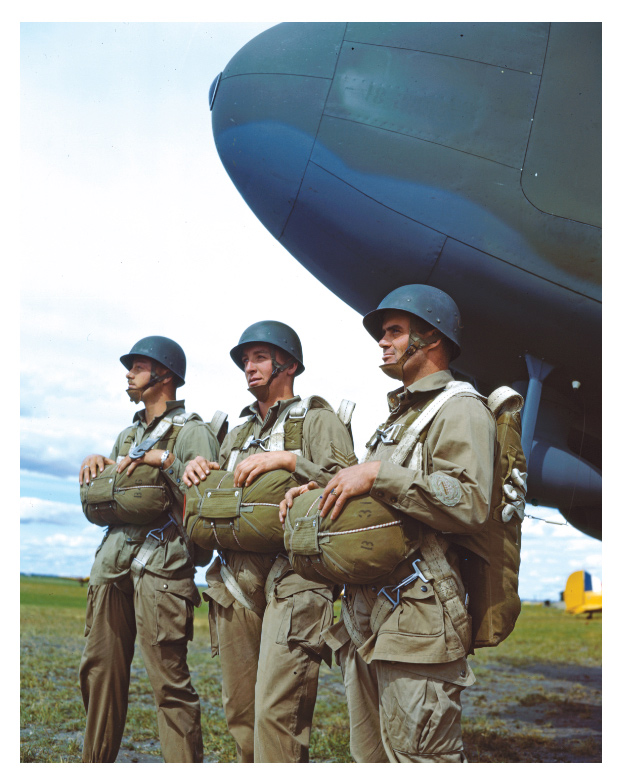

Airborne troops of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion with a jeep in Greven, Germany, on April 4, 1945.

In crossing the Rhine, the British and Canadians were expected to support the main weight of the assault coming from First United States Army. Crerar was to take Emmerich, then drive north to clear large parts of the Netherlands.

On March 23, the Canadians had a role in the British Operation Plunder, with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion dropping on German territory while the 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade of the 3rd Division assaulted the next day. Jan de Vries was one of the 475 Canadian paras who landed across the Rhine on that bright, sunny day.

“The Germans…opened up on us as we were coming out of the aircraft,” de Vries recounted later in life. “The field was covered with guys who had been killed or wounded. I heard bullets going by and I looked up and my chute was full of holes.”

A veteran of the D-Day drop, de Vries fought his way out of the desperate situation. So, too, did his surviving comrades, and they killed or captured about 600 Germans. In the early hours of March 24, the 9th Brigade, with the Highland Light Infantry and North Shore Regiment in the lead, surged across the river, but ran into the teeth of the enemy. Some of the most brutal fighting was around Bienen, when the North Nova Scotia Regiment battled through deep German defences. Three companies assaulted on the afternoon of March 25, advancing over dikes where the enemy had set up a crossfire of enfilading machine guns. The Novas had 112 killed and wounded. Artillery fire reduced Bienen to rubble the next day.

475

Members of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion dropped into German territory

“We kept moving day by day by day,” said one paratrooper. “Digging in, capturing village after village, and going like hell…fighting all the bloody way.”

The Canadian battles continued to March 30, when 8th Canadian Infantry Brigade snatched the Hochelten ridge, but their role

wound down after that, as they were ordered to move northward to save the Dutch.

With the Dutch situation causing much worry in upper political echelons, the Canadians were tasked with liberating the oppressed. Crerar sent his divisions north to free eastern Netherlands and the North Sea coast of Germany, while I Corps, fresh from Italy, was to attack toward the lower Rhine, at Arnhem, and in the western Dutch provinces, which were suffering the worst effects of food shortages. Drive the Germans “into the [PoW] cage, into the grave, or into the North Sea,” one report pointedly ordered.

Three divisions—2nd, 3rd and 4th Armoured—from Simonds’ II Corps set out in a wide formation on

April 1, using all available roads, moving northward. Reconnaissance units pushed into the soft underbelly of the German defenders, who were holding the countryside without much strength. This was very different fighting from the face-to-face battles of the Rhineland, although the Germans had skilfully laid mines and occasionally ambushed isolated units when it was to their advantage.

The 2nd Division headed to Groningen, advancing 120 kilometres in the first two weeks of April. Royal Canadian Engineers played a key role in bridging waterways and clearing roads of debris and fallen trees.

“We can hold off [the Germans’] best infantry, even his paratroopers, and man for man we can outfight him,” said one Canadian officer. Groningen fell on April 16 after a tough battle against Dutch SS troops, who had sided against their own people and were now fighting for their lives to avoid cruel punishment from their countrymen.

On the western advance, the 3rd Division faced a resolute enemy in Zutphen, a city on the IJssel River. After a two-day battle against first-class troops, the city fell to the Canadians on April 8. “It was house to house fighting all the way,” recalled Corporal Ray Lane of the Sherbrooke Fusiliers, who supported the infantry with Sherman Firefly tanks.

The division kept moving, advancing 185 kilometres in April and capturing 5,000 prisoners on the way to Leeuwarden near the Netherlands’ northeastern coast.

Most of the Germans had little desire to fight to the death, but there were pockets of fanatical resistance. The Canadians could never be sure when they were going to encounter a strongpoint, often turning to their flame-throwing Wasps to burn out the enemy.

“To be the target of a flame-thrower is most terrifying,” one Canadian trooper remarked. “Any of the enemy who survived threw down their weapons and sped through the fire and smoke toward us with arms in the air.”

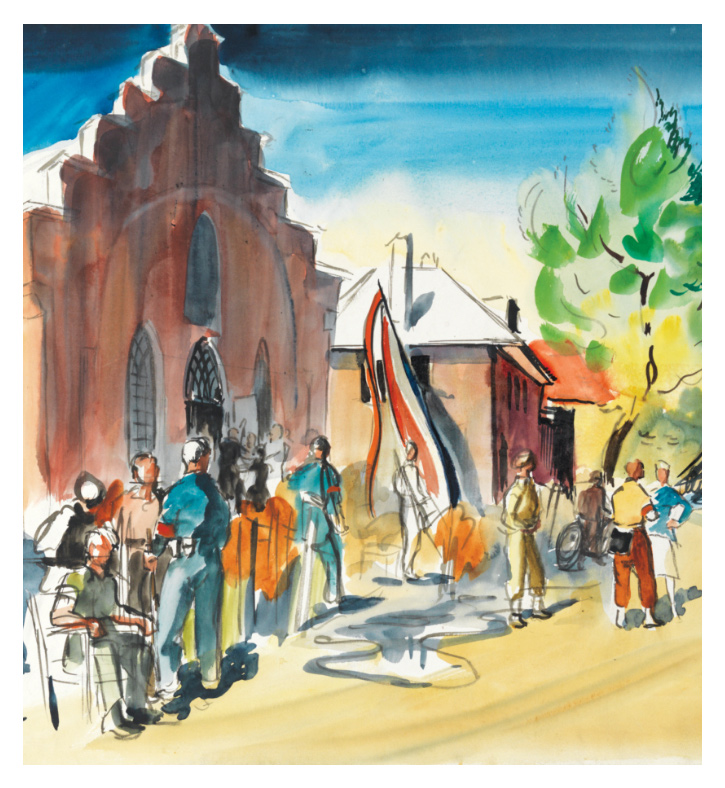

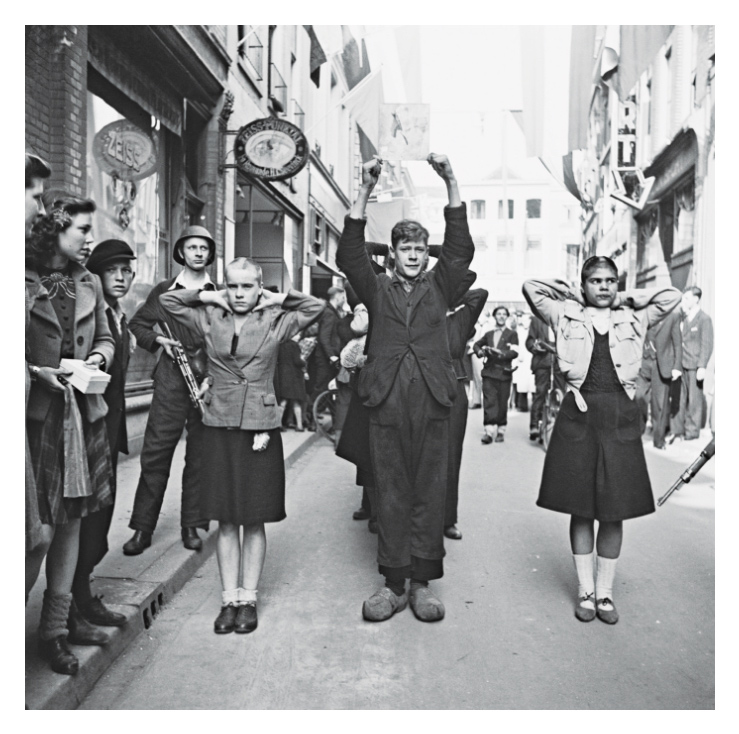

The emboldened Dutch Resistance helped the Canadians, often telling them where the enemy was hiding, and even conducting some attacks. When the Canucks moved on to new targets, the resistance took over civil affairs, rounding up Nazi sympathizers, many of whom were dragged into back alleys or basements and never seen again.

6,680

Tonnes of food dropped by Bomber Command in Operation Manna

4,000

Tonnes of food dropped in the american Operation Chowhound

Dutch women, young and old, who had taken up with German soldiers were also treated harshly. Publicly humiliated before jeering crowds, their hair was shorn with dull scissors, leaving bloodied scalps. Some Canadians tried to intervene. Dutch men and women with blood in their eyes gently but firmly turned the liberators away.

“We witnessed the sadistic emotions of revenge,” remarked Gunner James Brady, “and it sickens the human spirit.”

The 4th Armoured Division engaged enemy formations from early April, on the far right of Crerar’s army. Straddling the border of Germany and the Netherlands, the Canadians rode hard into enemy territory.

The German people watched them with anger, but did not rise up. There was some resistance, however, and the Canadians were quick to raze houses when snipers used them, and they hit hard when there was any sign of resistance.

“We are no longer a liberating army now that we are in Germany,” one Canadian remarked. “We come as conquerors.”

5,000

Number of German prisoners captured by 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on the 185-kilometre advance to Leeuwarden, Netherlands

Thousands of German soldiers surrendered. Still, the tired and spent Canadians were frustrated to have the enemy down arms in one village, then fight tenaciously in another.

“The tension you experience in these desperate brushes with death impacts on you physically and takes its toll,” recounted one trooper who had fought for months and was at the breaking point.

The weary Canadians pushed on, racing against time to liberate millions of Dutch on the verge of starvation. In late April, the food kitchens had closed down as there was nothing left to serve.

Amsterdam citizen Vert Voeten wondered if the Canadians would get to his city before the residents all died. “Today I saw two children dying in the street,” Voeten wrote. “They looked like small dead birds in winter.”