Image credits: Capt. Colin C. McDougall/DND/LAC/PA-190818

part three

battle of the rhineland

WITH THE SOVIETS crushing the Germans in the east, Allied bombers devastating the centre and western Allied forces preparing a new series of offensives, Hitler and his generals should have realized the war was lost.

But the Fuehrer continued to implore his people to fight on, with one of the lessons he took from the Great War being that the armies had surrendered too soon. In his deranged mind, now that the Jews and socialists were killed, the armies could fight onward unhindered by any stab-in-the-back dissenters.

Having imbibed countless forms of propaganda in film, radio, newspapers, speeches and classroom lectures through 13 years of Nazi rule, few German soldiers could think of anything other than battling to the end. Any who tried to surrender, or even talked about it, faced execution: at least 15,000 German soldiers were summarily murdered in the final months of the war.

Infantrymen of the North Shore Regiment board an Alligator amphibious tracked vehicle during Operation Veritable near Nijmegen, Netherlands, on Feb. 8, 1945.

Any who tried to surrender, or even talked about it, faced execution.

Terror and fanaticism drove many to keep fighting, as well as the realization that there might be little mercy for the German people who had exacted such trauma on the world. Having extended so little mercy to those they had conquered, many Germans knew they had to fight on no matter the cost.

Facing well-prepared defences west of the Rhine, Montgomery ordered a co-ordinated attack by First Canadian Army and Ninth United States Army. This would be a giant pincer movement to snap down on the enemy before Second British Army crossed the Rhine to thrust into Germany. The Battle of the Rhineland was the climactic series of set-piece battles for the Canadians.

With II Canadian Corps and 10 additional divisions, the 470,000-strong First Canadian Army became the largest force in Canadian history. Crerar was in command, with 3,400 tanks and 1,200 artillery pieces in his arsenal.

The Germans were vastly outnumbered, but they were fighting on terrain they knew well, and were dug-in with deep defences. They also had flooded much of the area anchored on the Rhine River. Crerar’s army would drive from the Dutch city of Nijmegen across the German border to Xanten and Geldern about 65 kilometres away in an ambitious lunge through the enemy-held Siegfried Line and two other defensive positions. The Germans had turned forests and villages here into strongpoints, and Crerar’s soldiers would clash over places like Kleve, Moyland, Kalkar, Wesel and Goch. It was a heavily wooded area, with not enough roads for the large army.

A massive artillery bombardment shook the front as 1,200 guns smashed the enemy positions.

Crerar was hoping for solid ground and planned the attack—code-named Operation Veritable—for late January 1945. But to the south, the Americans faced even more intense flooding as the Germans released the Roer River dams. Veritable was delayed to Feb. 8.

At 5 a.m. that day, a massive artillery bombardment shook the front as 1,200 guns smashed the enemy positions. It looked and felt like a Great War bombard-ment, with the Germans suffering under the hurricane of shellfire. The bombing stopped and started several times in an attempt to draw out hidden enemy gun batteries that started firing when the shells stopped. Skilled counter-battery officers located their positions and then clobbered them again.

“Our unit kept up a steady and sustained barrage for 13 and a half hours,” wrote J.P. Brady, a gunner with the 4th Medium Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery. Farther away from the start line, Allied bombers, including squadrons from 6 Group, RCAF, pulverized enemy positions around Cleve and other German fortresses.

British General Brian Horrocks of XXX Corps spearheaded the assault with his formations, while the 2nd and 3rd Canadian divisions were situated on the flooded northern front. In these narrow, water-constricted confines, only a few Canadian units could advance before the front widened. The water was so deep in places that men carrying heavy equipment could drown if they fell in.

Outer German defensive lines were pulverized as British units surged forward at 10:30 a.m., making good headway along the Nijmegen–Kleve road, advancing behind a creeping barrage and smoke screens. Flail tanks with heavy chains beat the ground to explode road mines. Canadian troopers of the 1st Canadian Armoured Carrier Regiment transported many of the infantry in their armoured bellies, cutting down on the wounds from stray artillery and small-arms fire. With additional tanks and self-propelled armoured guns, the spearhead of the attack was fully armoured.

470,000

Maximum Strength of First Canadian Army (reinforced by Allied units) commanded by General Harry Crerar, the largest force in Canadian history

A Sherman Crab tank conducts minesweeping tests in Britain on April 27, 1944.

Flail tanks with heavy chains beat the ground to explode road mines.

“The roads that were not flooded were seemingly bottomless pits of mud or under repair and therefore barred,” wrote war artist Charles Comfort. Heavy rain added to the misery and tens of thousands of soldiers and vehicles were caught in a massive traffic jam within the fire zone, unable to go forward, backward, left or right. It was a nightmare.

As the advance slowed, Allied airpower kept the enemy under cover. The city of Kleve was overrun by the British 43rd Division on Feb. 11. It was slow, grim going, and the spongy ground rendered tanks almost useless. With the Americans mired in water to the south, the Germans threw their reserves against the British and Canadians and the fighting became even more intense.

Eventually 10 German divisions and 1,000 new artillery pieces were stacked opposite Crerar’s army. The Canadians

and British drew in the enemy, as they did in Normandy, while the Americans worked to overcome natural obstacles—bocage in Normandy, flooded plains here. Once unleashed, they would be attacking a weakened German force.

More Canadian units were pushed into the widening battlefield after a week of fighting, and the Canadians began a series of fierce clashes. One of the most desperate was at Moyland Wood, where the Canadian Scottish, Royal Winnipeg Rifles and Regina Rifles battled German paratroopers. The enemy had high morale and fought aggressively amid the forest, which had many places from which to snipe and spring ambushes.

The Canadians slowly drove the paratroopers back, although there were many section-level battles and no front lines. Gunners on both sides poured shells into the woods, tearing apart the soldiers there. The area was only finally cleared on Feb. 21 in an audacious assault by the Winnipeg Rifles, who advanced behind a thick barrage. The cost was appallingly high, with more than 500 Canadian casualties.

Operation Veritable

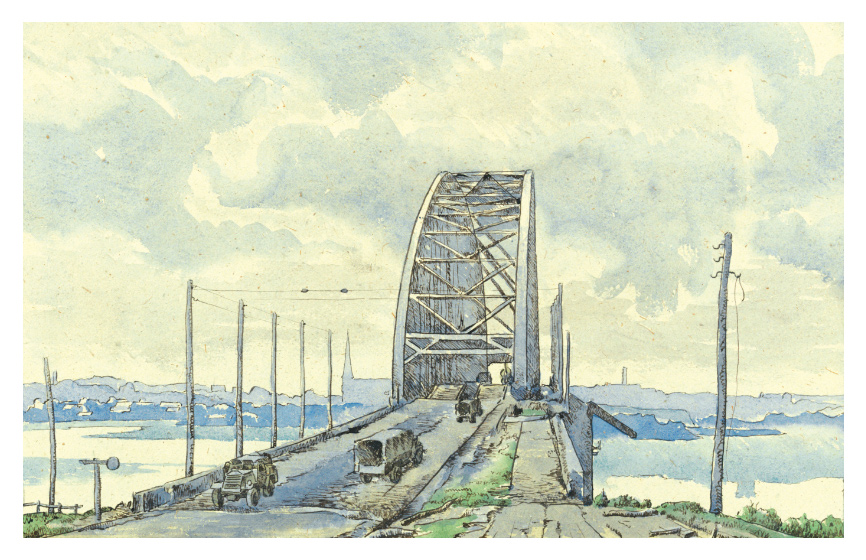

A pincer movement through the Reichswald by First Canadian Army in February and March 1945.

Infantrymen of the Regina Rifles prepare to fight at Moyland Wood near Kalkar, Germany, on Feb. 16, 1945.

Tired, sleep-deprived and soaked to the bone, the Canadians continued to cut through the enemy defences. Both sides were bloody-minded and went at it hammer and tongs. The armoured regiments eventually found more solid ground and became more effective, with intense battles around Kalkar where Fort Garry Horse Sherman Firefly tanks slugged it out with Panzers and Mark IVs on Feb. 21.

On the same day, the Americans started their long-awaited drive against a weakened battle front. German resistance collapsed. The Americans crossed the Roer on Feb. 23 and broke out for the Rhine two days later. With American success to the south, the Germans began to pull back.

There was a pause on Montgomery’s front before the British and Canadians regrouped for Operation Blockbuster—an advance on German positions in the Hochwald Forest—beginning on Feb. 26. The enemy was clinging to his last line of defence, thinly held by infantry but bristling with anti-tank guns.

The Canadians continued to manoeuvre in this terrible landscape.

Crerar ordered Simonds to plan the battle, and he chose to keep the pressure on the Germans in the Hochwald, even though the Americans were already thrusting deep into the enemy lines. A frontal assault against a fortified enemy position would be costly, but Simonds felt it would keep the enemy to his front and not allow them to regroup. The sharp end units knew little about the larger strategic picture, but they had watched the Germans fight tenaciously to protect their homeland and few expected the next campaign to be easy.

In the attack on Feb. 26, the 1st and 3rd divisions, followed by the 4th Armoured Division, crashed into the enemy’s defences. Germany’s dug-in 88-millimetre anti-tank guns tore through the advancing Shermans. Dark smoke wafted over the battlefield and the smell of roasting flesh left men gagging. The Canadians continued to manoeuvre in this terrible landscape, often in battle groups consisting of infantry, armour and artillery.

After several days of combat, the Canadians advanced on a 17-kilometre front. Fighting in several ad hoc battle groups, they scratched their way through the dense trees of the Hochwald. Untold stories of courage and bravery mixed with immense suffering and loss in the many battles along the way. The whole area, recounted a major in the Lake Superior Regiment, “became a veritable hell.”

There was a pause on Montgomery’s front before the British and Canadians regrouped for Operation Blockbuster—an advance on German positions in the Hochwald Forest—beginning on Feb. 26. The enemy was clinging to his last line of defence, thinly held by infantry but bristling with anti-tank guns.

Crerar ordered Simonds to plan the battle, and he chose to keep the pressure on the Germans in the Hochwald, even though the Americans were already thrusting deep into the enemy lines. A frontal assault against a fortified enemy position would be costly, but Simonds felt it would keep the enemy to his front and not allow them to regroup. The sharp end units knew little about the larger strategic picture, but they had watched the Germans fight tenaciously to protect their homeland and few expected the next campaign to be easy.

In the attack on Feb. 26, the 1st and 3rd divisions, followed by the 4th Armoured Division, crashed into the enemy’s defences. Germany’s dug-in 88-millimetre anti-tank guns tore through the advancing Shermans. Dark smoke wafted over the battlefield and the smell of roasting flesh left men gagging. The Canadians continued to manoeuvre in this terrible landscape, often in battle groups consisting of infantry, armour and artillery. As the Canadians drove on, the dead were left motionless on the battlefield.

500

Number of Canadian casualties in the battle for Moyland Wood

379

Canadian officers killed or wounded in March 1945

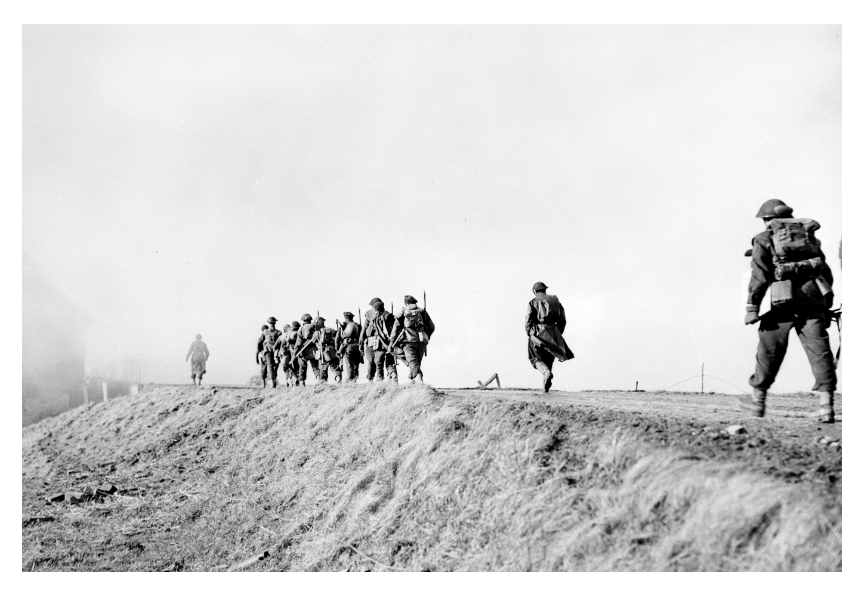

Riflemen H.W. Brownjohn, R.A. Hofferd and A. Hill of the Regina Rifles make their way through Germany on Feb. 9.

Canadian and British divisions cleaned up the remaining strongpoints.

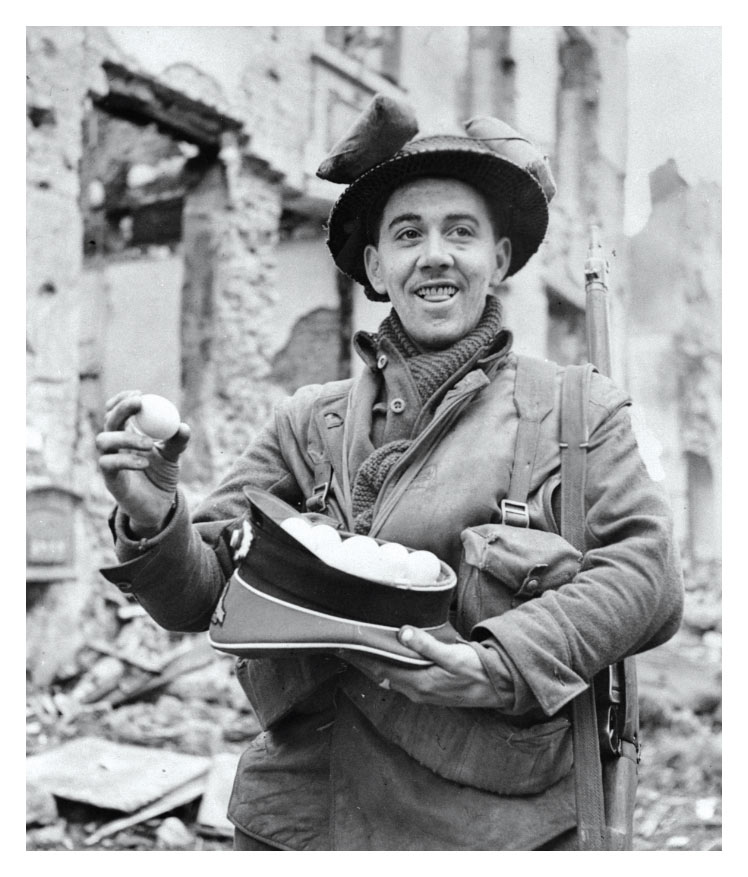

Private G. Foreman of the 43rd British Division holds a German officer’s cap loaded with salvaged eggs in Kalkar, Germany, on Feb. 28.

Sometimes a glimpse of a past combat could be seen in a shell crater with a circle of dead men around it, or a line of soldiers lying where they fell, caught by machine-gun fire. Bloodied bandages often indicated the failed emergency care from comrades and stretcher-bearers who exposed themselves to aid the wounded.

It would be days before grave units scoured the front looking for the dead. When found, each body was examined and the name and serial number recorded from identification tags. Personal objects were collected and sent back to the regiment, ultimately to find their way to grieving loved ones in Canada. Men were buried individually, in small groups, and sometimes only in pieces.

With the Americans thrusting deep into the enemy lines and approaching the Rhine, the Germans were forced to retreat. Canadian and British divisions cleaned up the remaining strongpoints and set off for Xanten to the east of the Hochwald.

Thousands of surrendering German soldiers were captured, but bitter-enders and elite paratroopers often fought on. This was the case in Xanten, where the Royal Hamilton Light Infantry ran into a series of ambushes and suffered 134 casualties in what was anticipated to be a mop-up job. Nothing was easy with the Germans, and Xanten did not fall until March 8.

“The Germans fought like hell—demons,” Denis Whitaker, then commander of the Royal Hamiltons, recounted later in life. “This was their last desperate stand for their homeland.”

Hordes of German prisoners—dirty, ragged, some mere teenagers or old men—were moved to the rear as the battle wound down on March 10. It was a month of bitter combat and the Canadians lost 379 officers and 4,925 other ranks killed and wounded. The Americans suffered some 7,300 casualties, while the British were down 16,000 soldiers. But the Germans had been delivered an even more severe blow, with around 90,000 casualties. Canadian survivors looked at their shattered regiments and wondered if the war’s end would ever come.

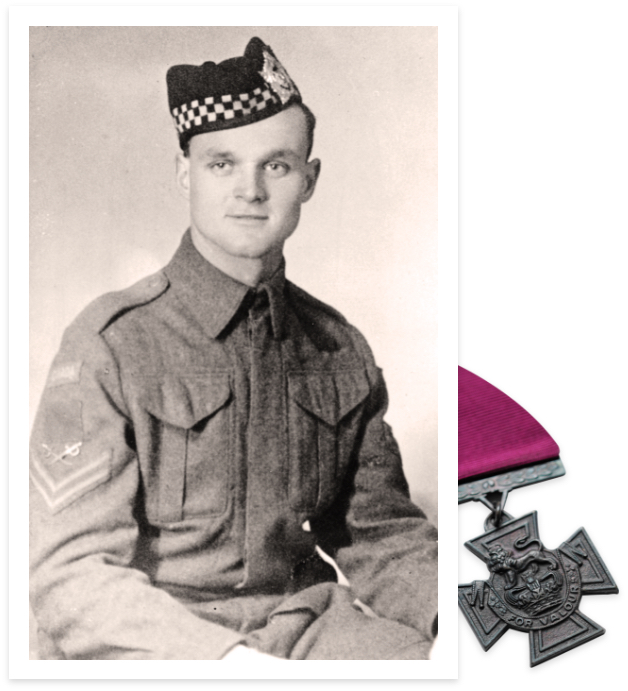

Sergeant Aubrey Cosens earned a Victoria Cross directing a tank through pitched battle by riding it like a metal stallion.

THE QUEEN'S OWN RIFLES had seen combat since D-Day, clawing their way onto Juno Beach, advancing inland, and fighting through Normandy and all the battles that followed.

After more than eight months of war, many of the originals were gone by the time Operation Blockbuster started on Feb. 26, 1945. They were recovering from wounds in England or Canada, or given safer jobs to the rear, or buried in shallow graves. A core of diehards remained, however, as well as some who had been wounded and returned to the regiment. Aubrey Cosens was born in Latchford, Ont., the son of a Great War veteran. He was working as a section hand on the Temiskaming and Northern Ontario Railway when Canada went to war. He enlisted at the age of 23 in 1940 and served as a sergeant with the Rifles as a Normandy reinforcement.

The Queen’s Own fought into Mooshof, near Uedem, Germany, in the early hours of Feb. 26. The enemy twice hurled the Rifles back. When his platoon commander was killed, Cosens took over. Few men were left standing, but Cosens rallied them as the enemy converged on their vulnerable position.

22

Number of Germans killed by Sergeant Aubrey Cosens. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross

A tank from the 1st Hussars was in the distance, but was unaware of the impending attack. Soon to be overrun, Cosens ordered his four comrades to lay down covering fire and then he dashed to the tank. Enemy bullets kicked up the ground around him and mortar bombs smashed down. Somehow, he survived. He jumped on the armoured vehicle, banged on the

hull, and directed its fire.

As the enemy attackers were cut down, Cosens told the tank crew to break through a far building, where a number of Germans were holed up. Like a cowboy riding a metal stallion, he rode into battle, jumping from the tank with a Sten submachine gun in hand before it crashed into the brick farmhouse.

He charged through the hole, shooting wildly, taking on about 40 Germans. Moving and firing, from room to room, he was a man possessed. Some 22 Germans were killed and the rest wisely surrendered. As Cosens was making his way back to report to his superiors later that day, he was killed by a sniper’s bullet.It was men like Cosens who helped break the enemy defenders. For his unparalleled courage, he was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

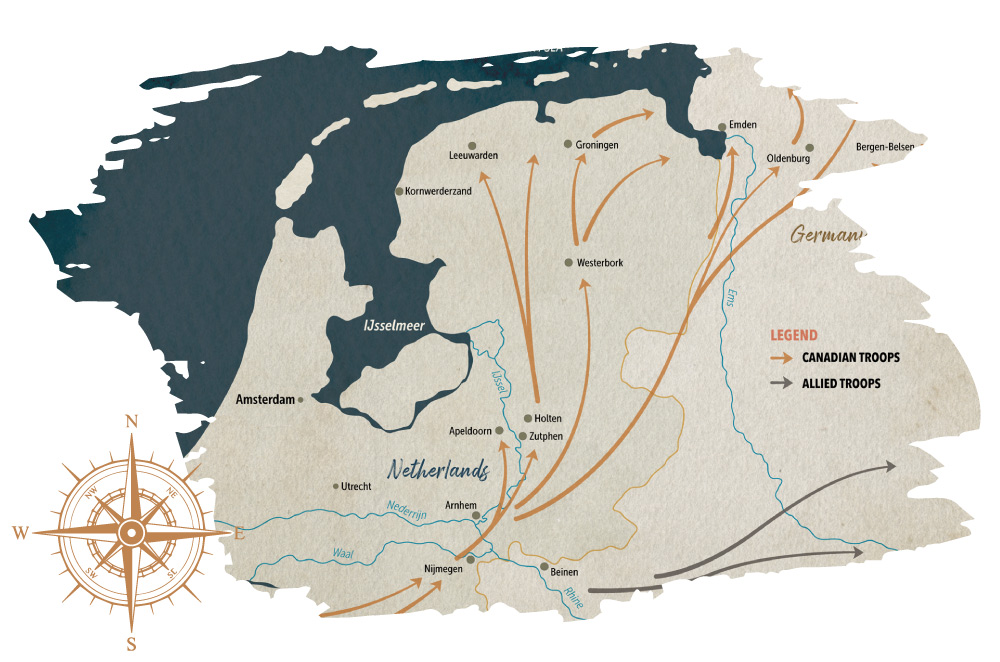

Map

to the sea

WITH supply routes cut off and the inevitable end looming as Allied forces swept across the Netherlands, German forces resorted to starving the Dutch citizenry to keep themselves alive. The Hunger Winter of 1944-45 exacted a heavy toll, particularly on the elderly and the young. As the liberators pushed eastard, the Germans formed up on the far bank of the Rhine River, preparing for a final defence of the homeland. On March 23, airborne troops became the first Canadian soldier to set foot in Germany, landing with British paras behind enemy lines. Ground troops followed across the Rhine the next day. The final push was on.

View the map