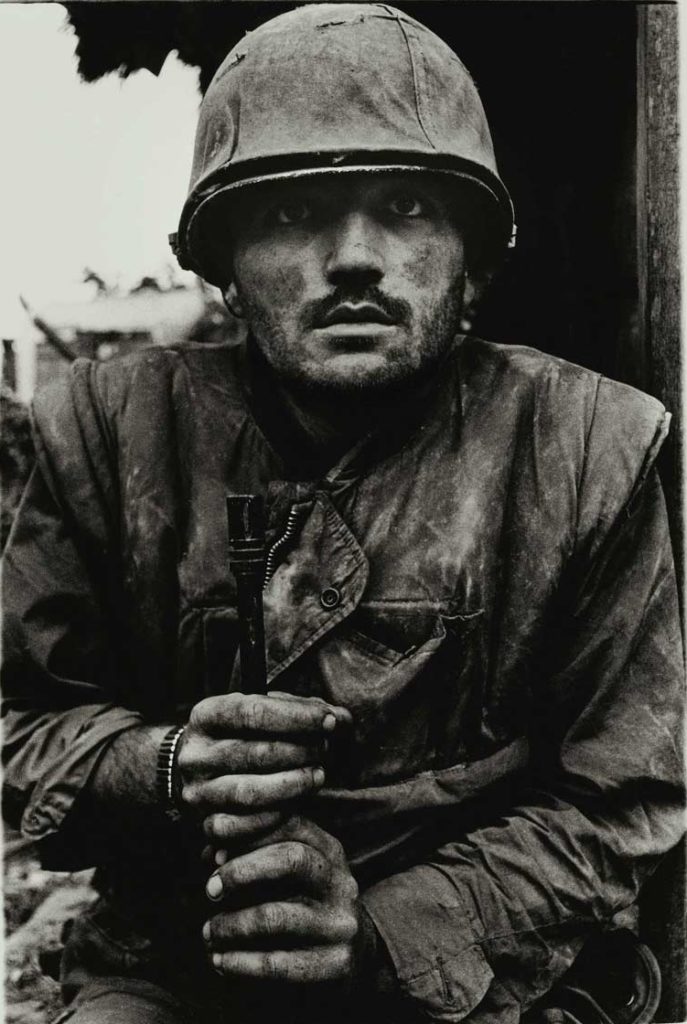

Private Heath Matthews of the Royal Canadian Regiment awaits medical attention outside a forward aid station after two of his mates were killed during a nighttime raid on a Chinese position on June 22, 1952. [Paul J. Tomelin/DND/LAC/PA-128850]

A sergeant in the Canadian Army Film and Photo Unit, Tomelin was deployed to the Korean Peninsula for one year in 1951-52. He managed to wrangle another six months in-country, during which he said he got some of his best images.

None was better than his June 22, 1952, photograph of a bloodied and battered Private Heath Matthews of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, wounded by shrapnel and looking old beyond his 19 years.

Matthews, a signaller, was standing outside a medical tent awaiting attention after a company-strength raid the night before on an enemy position near Hill 166, the dominant feature on the Chinese side of the Nabu-ri Valley. Canadian units suffered some 131 casualties in the area that May and June, including two killed and several wounded during the Charlie Company raid.

“I noticed a soldier leaning up against the [sandbags outside the] hilltop regimental aid post,” Tomelin recalled in an interview for a unit history three years before he died in 2016. “I wanted to get a photograph of him earlier, but I would have had to do it with a flash and I felt that wouldn’t reproduce the images as well as natural light, so I kept an eye on this soldier as he moved in the lineup.

Known as “The Face of War,” it became Tomelin’s signature picture, and an icon in the annals of Canadian photography.

“He was less injured than many of the others and he was getting close to the entrance. It was getting to be around four o’clock in the morning and daylight and he happened to be at the back entrance to the regimental aid post and I realized that if I didn’t get it now I wouldn’t get it.

“So, I raised my camera to take his photograph and he pushed himself away with disgust that he didn’t want his photograph taken. He was going to leave so I raised both my hands and I said, ‘Please just go back the way you were.’ It took no persuasion, he dropped right back against the sandbags and asked ‘Where do you want me to look?’ I just raised my arms and more or less pointed over my left shoulder the direction in which he was looking generally and got him looking over my shoulder and I raised the camera again, focused and took the photograph.”

Known as “The Face of War,” it became Tomelin’s signature picture and an icon in the annals of Canadian photography.

Born in Alberton, P.E.I., Matthews died in December 2013 at Leawood, Kansas. He was 81.

U.S. Marine Corporal Leonard Hayworth, out of ammunition and in tears after losing all but two of his squad mates. [David Douglas Duncan/Life Magazine]

The pre-eminent lensman of the Korean War was David Douglas Duncan, a Second World War U.S. Marine photographer who went on to become one of the great conflict photojournalists. He recorded two of Korea’s most compelling images, both in 1950.

The first was of Marine Corporal Leonard Hayworth, out of ammunition and in tears after losing all but two of his squad mates. Hayworth was killed in action on Sept. 24, 1950, three months after the war began. He was just 22.

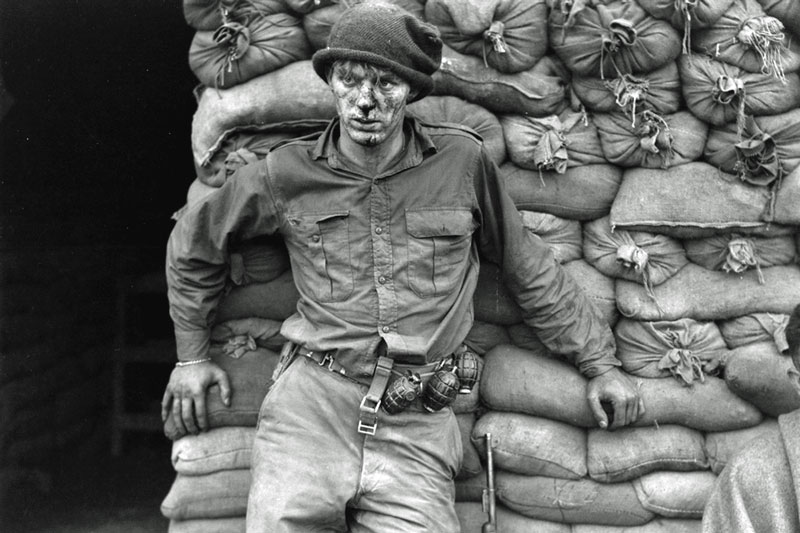

The second Duncan photograph of note (there were many) stands with Tomelin’s among the war’s most compelling photographs—a dirty, miserable U.S. Marine huddled with his meagre rations against the cold of a winter near Chosin.

The hooded grunt is holding a can of frozen beans, his 1,000-yard gaze emblematic of his unit’s December 1950 retreat after they had been cut off by Chinese forces at the Chosin Reservoir northeast of Pyongyang.

A Marine huddles with his meagre rations near Chosin in December 1950. [David Douglas Duncan/Life Magazine]

“I asked him, ‘If I were God, what would you want for Christmas?’” Duncan recalled before his death in 2018 at age 102. “He just looked up into the sky and said, ‘Give me tomorrow.’”

Duncan’s Korean War photographs made up his 1951 book, This Is War!, the proceeds of which went to widows and children of Marines killed in the conflict.

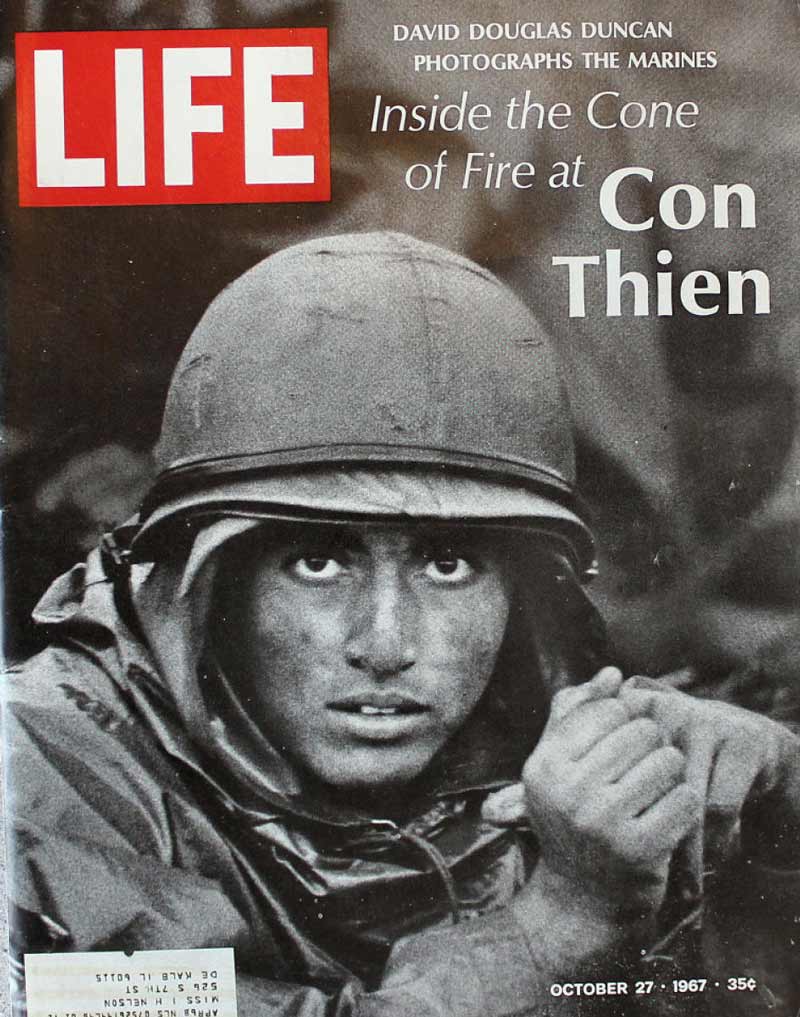

Duncan went on to photograph the Vietnam War, where his work continued to make an impact. His Oct. 27, 1967, picture of a young soldier looking up into the camera during the Battle of Con Thien is among Life Magazine’s most famous covers.

Duncan’s Oct. 27, 1967, Life cover came to symbolize the youth of the Vietnam War. [David Douglas Duncan/Life Magazine]

The Don McCullin archive is packed with stunning photographs from dozens of conflicts, big and small.

The Briton’s image of a young, shell-shocked soldier from the 5th Marine Battalion staring into the void during ferocious fighting at Hue, South Vietnam, in 1968 has become one of his most recognized.

In a 2014 interview with the Tate Britain art museum, McCullin said: “I just found him sitting on a wall. He’d got to a point in the battle, or in his life, that he couldn’t take any more of it. And I asked somebody ‘What’s the matter with him?’ And he said ‘He’s shell shocked.’Minutes after he took the pictures, there was an “almighty explosion.”

“And so I kind of dropped down on my knees and took five frames with my 35mm camera of this soldier and he never blinked an eye; his eyes were completely fixed on one place,” said McCullin. “He was staring off into the horizon and every negative I took of this man is identical; I checked them all out thoroughly.”

Minutes after he took the pictures, there was an “almighty explosion.”

“I don’t know whether that explosion, which was an incoming mortar shell, killed this soldier. I knew it wounded some people in there. I feel slightly ashamed I didn’t go to check to see whether he was injured or still alive.”

A 2018 investigation by The Australian’s Anthony Lloyd suggests that he survived.

Though Lloyd was never able to identify the young Marine, a comrade, Myron Harrington, said the shell-shocked soldier was taken away and never returned to his mates in Delta Company.

Marine Staff Sergeant Robert (Cajun Bob) Thoms said he heard the soldier had been sent to a psychiatric ward in a catatonic state.

“The personal medical records are not accessible,” Lloyd wrote. “The trail went cold. I had walked through the valley of the shadow of Marines’ memories in search of him all the way from D.C. to Tennessee, from the Arizona sun to the snows of Michigan—and I lost him.”

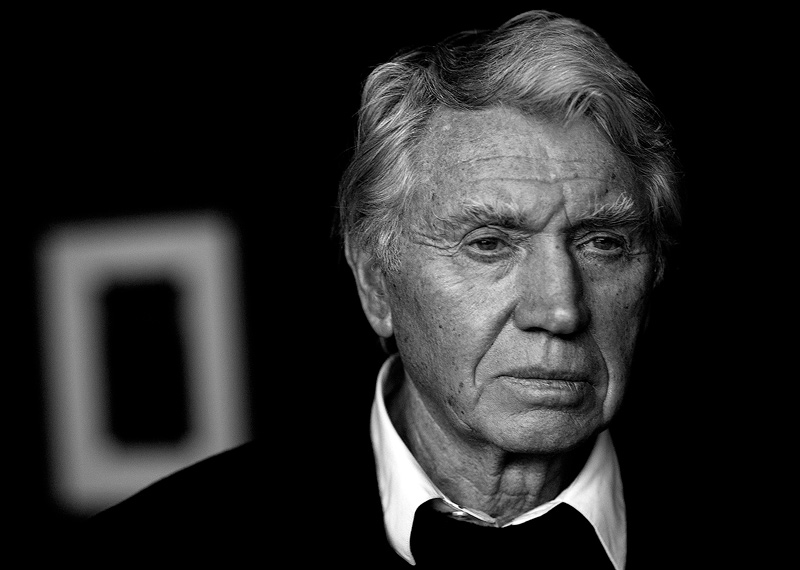

Don McCullin photographed disasters and war for 50 years. Now 85, he seeks peace in English landscapes. [Stephen J. Thorne]

A print of the photograph sold at auction for £20,000 (about C$35,000) in 2019. After years on war fronts and in disaster zones, McCullin—now 85—shoots pastoral English landscapes near his home.

There was no shortage of impactful photographs during the Second World War, some of them from parts of the six-year conflict largely unfamiliar to Canadians.

John Florea’s picture of a weeping German boy in Wehrmacht uniform appeared to show the desperation and hopelessness of Hitler’s last stand through the tear-filled eyes of a child soldier.

Hans-Georg Henke, a 16-year-old anti-aircraft gun crewman, weeps after he was captured by American troops in 1945. [John Florea]

Henke maintained throughout his life that he was based in Stettin with an 88mm gun battery. He said advancing Soviet forces pushed the Germans back toward Rostock, where he claimed his unit was overrun and he was taken prisoner.

Florea said the boy was not sobbing because his world had crumbled. He said Henke was overcome by combat shock after his unit was overrun by American, not Soviet, forces. After the war, Henke joined the Communist Party and chose to live in East Germany. He died in October 1997 at Brandenburg, age 69.

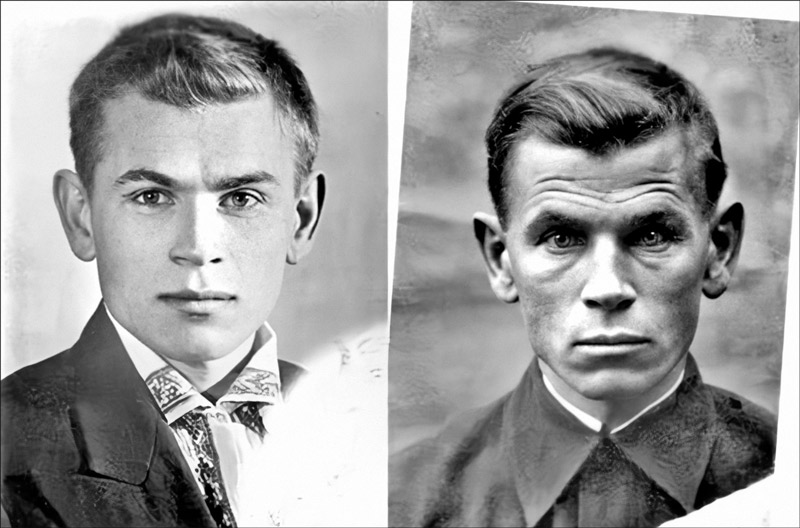

In a museum in the Russian city of Krasnoyarsk hang two photographs side-by-side.

They are of a Russian artist, Evgeny Stepanovich Kobytev, though you might never know they were the same man.

“This is the human face after four years of war.”

On the left hangs a picture taken the day in June 1941 that Kobytev left for the Eastern Front after German forces launched Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s ill-considered invasion of the Soviet Union. On the right hangs a portrait taken the day he returned in 1945.

Russian Evgeny Stepanovich Kobytev before and after serving four years in the Red Army during the Second World War.

Talk about a thousand-yard state.

As one historical website put it: “This is the human face after four years of war. The first picture looks at you; the second one looks through you.”

The not-so-young artist (Kobytev is believed to have been 30) had just graduated with honours from the Kyiv Art Institute when he “volunteered” to defend the Motherland. He painted portraits and panoramas of daily life.

His Red Army regiment was soon engaged in a fierce battle to protect the small town of Pripyat, which lies between Kyiv and Kharkov.

Kobytev was wounded in the leg and captured in September 1941. He was taken to the notorious Khorol concentration camp, known as the Khorol Pit, where 90,000 civilians and prisoners of war died.

Kobytev escaped in 1943, rejoined the Red Army, and fought the rest of the war through Ukraine, Moldova, Poland and Germany. He was declared a Hero of the Soviet Union. Some 26 million Soviets are estimated to have died during the Second World War. Some say that without their sacrifices, the war may well have been lost.

After history’s bloodiest war, Kobytev was elected to his city council and took charge of cultural activities in the region. He died in 1973.

It is one of the primary motivations of many war photographers that their images will make a difference. Some images, such as Joe Rosenthal’s “Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima,” have helped end wars through bond drives or, like Eddie Adams’ “Saigon Street Execution,” inspired anti-war demonstrations.

Photographs document the brutality, suffering, waste and ultimate futility of war. But wars continue to be fought, and the young grow old before their time.

Advertisement