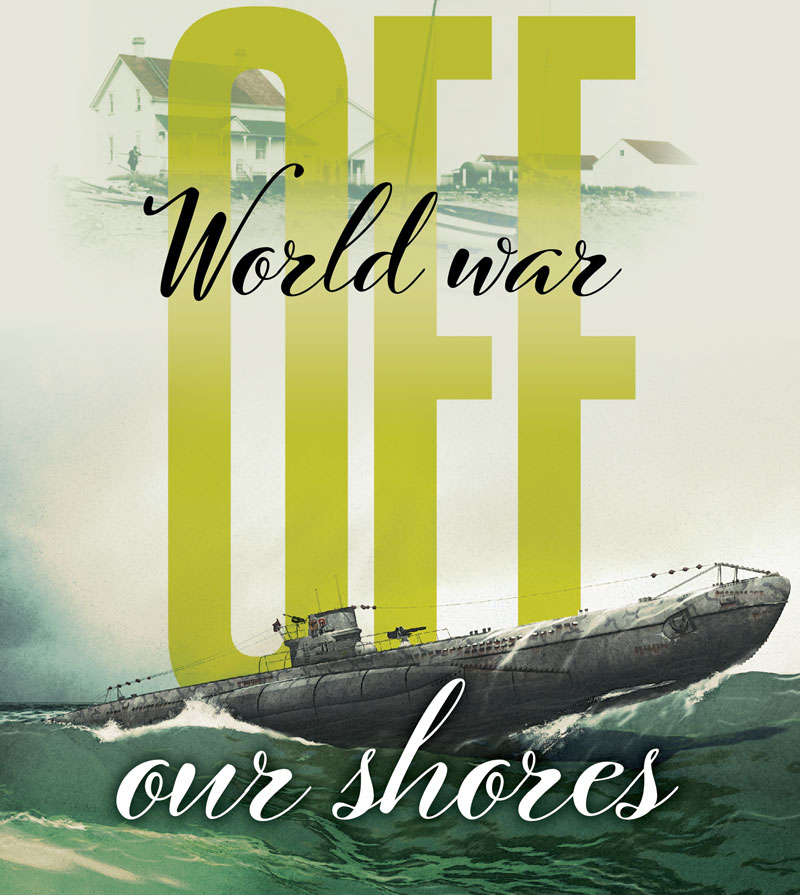

In 1942, U-boats started appearing off North America, including U-69, which sank the merchant vessel Carolus near the lighthouse at Pointe Mitis, Que.

How the Battle of the St. Lawrence transformed the lives of Newfoundlanders and Quebecers

It was around midnight on the night of Oct. 8-9, 1942, and in the cozy living room of the lightkeeper’s house on the St. Lawrence River at Pointe Mitis, Que., 21-year-old David Gendron was in the throes of composing a love letter.

The rest of the household was asleep—seven of his siblings; the local schoolteacher who boarded with them; Gendron’s mother, Eugenie, and his father, the lightkeeper, Octave.

On the waters offshore and in the world beyond, a war was going on, far away and ever closer. The Battle of the Atlantic had spilled into the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the river itself.

What would become known as the Battle of the St. Lawrence had already claimed dozens of victims, marking the first time lives were taken by hostile action on Canadian inshore waters since the War of 1812.

More than 400 sailors, civilians and merchantmen died during the three shipping seasons that German Admiral Karl Dönitz’s unterseeboots hunted close to Canadian shores and forced a partial shutdown of gulf shipping spanning parts of three years. Most of the losses would come in the first year, 1942.

In total, U-boats would sink 23 merchant ships along with four Canadian navy vessels in and around the estuary, along with five more cargo carriers at Bell Island, Nfld.

Back in July, Octave had reported sighting a submarine around 9 p.m. on the surface in the bay between his light and the summer resort on the far bank. It stayed for about an hour while tourists danced on the beach nearby.

Shortly afterward, reports surfaced in Germany that a U-boat “commander claimed he and his crew listened to dance music in Canada and watched the lights of cars travelling along a highway,” said a story in the Montreal Gazette dated Oct. 15, 1942. It noted that the scenic Gaspé route, a tourist favourite, ran along the coast near Métis Beach—a stone’s throw from Pointe Mitis.

On that October evening, however, with autumn colours fading and a damp chill in the air, there were no joyful tourists, only grim-faced mariners cautiously navigating the big river that had been a transitway of Indigenous Peoples since time immemorial; that Jacques Cartier first sailed in 1534; that was now, some four centuries later, a lifeline of international trade and commerce, transport and supply—and a battleground where explosive violence and cruel death had infiltrated civilian psyches in small towns all along the scenic Gaspé Peninsula.

Suddenly a dull boom rumbled in from the river, rattling the Gendron family’s living-room windows in their wooden frames. Young David, whiling away his graveyard shift as the assistant lightkeeper, was jarred from his writing and looked up from the rolltop desk. He said later it was 12:10 a.m. U-boat logs recorded the first strike at three minutes before midnight.

Then came a series of thunderous cracks, amplified by the moisture-laden air, that shook the white wooden, red-roofed house on its square stone foundation.

It was five days before the ferry Caribou would be sunk in the Cabot Strait and here on the river, the perpetrator of that tragedy, German U-boat skipper Ulrich Gräf commanding U-69, had just fired a volley of torpedoes.

It took only one to dispatch the 2,375-ton Carolus. The vessel broke in two and the little Canadian steamer with its load of empty barrels plunged bow-first to the river bottom. Barrels stored on the afterdeck popped their moorings and others inside the hold came tumbling out as the stern settled and sank. It all took just two minutes.

At the first reverberations, Octave came rushing downstairs and raced out the door. He scurried a few metres over to the red-and-white painted concrete lighthouse and huffed and puffed his way almost eight storeys up its winding staircase to the gallery deck adjacent to the lightroom, where he breathlessly peered through the old brass telescope.

Rain squalls had been sweeping across the river all evening but, according to Gräf’s log, the river itself was “mirror-calm” with a “strong phosphorescence.” As Octave now discovered, visibility was good enough that it didn’t take a nautical warfare expert to conclude a German submarine was doing its dirty work less than five kilometres from the beach below, where his children had frolicked all summer long.

Lightkeeper Octave Gendron and his wife Eugenie lived at Pointe Mitis from 1936 until 1954.[Paul Gendron/ Reford Gardens]

“For the Gendron family, the battle of Oct. 9, 1942, in front of Métis marked their life. They were in the line of fire.

U-69 had fired from the surface. Two Canadian corvettes, Hepatica and Arrowhead, escorting convoy NL-9 from Labrador to Quebec, were launching illuminating star shells overhead, and may even have been firing their deck guns at the vanishing U-boat.

Just a month earlier, at Saint-Yvon, Que., 300 kilometres along the peninsula near the river’s mouth, a torpedo had slammed into the shoreline, the resulting blast shattering windows in the village. Octave feared for hearth and home, and even thought that the German was firing at the lighthouse itself.

But phones were at a premium along the Gaspé at the time and, despite the pivotal role he fulfilled—being positioned, as he was, at the water’s edge 24-7—Octave had none.

The Royal Canadian Air Force station at Mont-Joli, Que., was 20 kilometres away and the nearest phone was in the village five kilometres down a bumpy track and out the pitted gravel road. He took the youngest of his children away from the house.

“I didn’t count” the kids, he told Maclean’s magazine seven years later. “I just kept piling them into the car until it wouldn’t hold any more, closed the door, and drove for the phone as fast as I could.”

It was an exasperatingly slow trip. Octave deposited his sleepy-eyed children at the end of the access road, far enough from the beach that his worries could be assuaged. He told the oldest to watch over them, then set out to call his report in.

Six minutes after he hung up, he said, a bomber lumbered out over the point, headed straight for the action.

“After that,” he told Maclean’s writer Jack McNaught, “the government gave me a phone for the house so I could make my reports faster; which I’d been at them all along to do.”

Octave was also granted permission that night to shut off the lighthouse lamp, ceasing its continuous, four-times-a-minute rotation.

The issue of blackouts had been a matter of debate in Ottawa. Towns and villages had taken to dimming lights—brownouts—but Pointe Mitis, for one, averaged 1,000 hours of debate in Ottawa. Towns and villages had taken to dimming lights—brownouts—but Pointe Mitis, for one, averaged 1,000 hours of fog a year and authorities, in their wisdom, had apparently deemed navigational aids more critical than whatever measures might help mitigate the U-boat threat. They had ordered navigational lights to stay on until told otherwise.

A system was eventually developed using four-times-daily CBC and Radio-Canada broadcasts to signal lightkeepers when to shut off their beacons. “A” for “Alphonse” was sent three times to keep the light burning; “B” for “bonbon” meant a U-boat had been sighted and operations were to shut down until further notice.

But, while defensive measures were being stepped up for convoys running men and materiel from Montreal and Quebec City to Labrador and the main East Coast assembly points and back, brazen U-boat skippers were routinely logging the fact that the merchants’ running lights and the navigational buoys that guided them, along with streetlamps, houses and lighthouses ashore, were on.

As it was, 11 Carolus crew died that night; 19 others were rescued.

Gräf submerged and, after some cat-and-mouse manoeuvring, punctuated by a volley of depth charges, U-69 slunk away and departed the gulf, leaving in its wake an uproar over the sinking a mere 300 kilometres from Quebec City. Gräf was about to cause even greater turmoil off the southwest coast of Newfoundland.

Back at Pointe Mitis, Octave Gendron would return to some semblance of the normal life he had forged on the little strip of land jutting into the St. Lawrence. He served as Pointe Mitis lightkeeper for 18 years, until 1954.

David Gendron finished the love letter to his sweetheart, Simone Leblanc. The pair eventually married, had seven children, and were together for 45 years.

Their 76-year-old son, Paul, told Legion Magazine his dad went on to work at the Canadian National Railway for 15 years before serving as director of Reford Gardens (Jardins de Métis), a national historic site at Grand-Métis, Que., for 25.

He said the events of that night in 1942 remain a part of family lore.

“For the Gendron family, the battle of Oct. 9, 1942, in front of Métis marked their life,” he said in an e-mail interview. “They were in the line of fire.

“My grandfather Octave Gendron…died in 1975 and he often spoke to us about the Battle of the St. Lawrence.”

As he crossed the Cabot Strait on the night of Oct. 13-14, Gräf sighted smoke belching from the stack of the ferry Caribou. The government vessel was en route from Sydney, N.S., to Port aux Basques, Nfld. It was 60 kilometres from the dock with 73 civilians, 118 military personnel and 46 hands aboard. It was 3:21 a.m.

The German claimed he misidentified the 2,222-ton ferry and its escort, the 672-ton minesweeper Grandmere, as a 6,500-ton troop ship and “two-stack destroyer.” At 3:40 a.m., he unleashed a lone torpedo, striking the Caribou starboard.

The ferry sunk in four minutes, taking 137 lives with it. Gräf dove, then made for the sounds of his sinking prey, knowing that the survivors in the water above would keep Grandmere from depth-charging his boat any more than it already had. He eventually launched a decoy and escaped.

Grandmere’s skipper, Lieutenant (N) James Cuthbert, didn’t give up the chase and go back for survivors until 6:30 a.m.—to some at the time, a controversial set of priorities, but it was procedure and to do otherwise would have put his own vessel at risk.

Fifteen-month-old Leonard Shiers of Halifax was the only one of 11 children aboard Caribou to survive. Of the 46-man crew, mostly Newfoundlanders, only 15 made it home. Five families in particular suffered mightily: the Tappers (five dead), the Toppers (four), the Allens (three), the Skinners (three) and the Tavernors (Captain Benjamin and his two sons).

Area fishing schooners chartered by the Newfoundland Railway Company recovered 34 bodies.

The Royalist newspaper in St. John’s declared the attack “a useless crime.”

“It will have no effect upon the course of the war except to steel our resolve that the Nazi blot on humanity must be eliminated from our world,” it said.

In Port aux Basques, the Oct. 18 funeral procession for six of the victims stretched two kilometres.

Decades later, Norman Crane, a Newfoundland Ranger who helped in the recovery effort, told Nathan M. Greenfield, author of The Battle of the St. Lawrence, that the town at the centre of “maybe 2,000 people” was in shock.

“In 1942, Port-aux-Basques was not like small towns on the mainland,” Crane said. “It was more like a 19th century town. They were a rough-cut bunch like most communities on the sea were. But they were also very respectful.

“The loss of the Caribou affected Port-aux-Basques more than you can imagine today,” he continued. “Ben Tavernor wasn’t just a well-liked captain of the Caribou, he was a respected man, known to have devoted his life to his boat and thus to their link to the outside world. His sons weren’t just fun-loving fellows—although they were—they were Ben Tavernor’s sons, and that counted for a lot.”

Gräf and his entire 45-member crew would be lost in the North Atlantic east of Newfoundland the following February.

The war’s single greatest loss in near-shore waters was 137 people who died in the sinking of the ferry Caribou. [DND]

By the end of the summer of ’42, residents along the coasts of Quebec and parts of the Dominion of Newfoundland, including Labrador, were attuned to the comings and goings of convoys and virtually any other floating object.

It’s a safe bet that many had seen more of the war than most other civilians in Canada.

U-boat strikes had become almost a familiar, though dreaded, part of life, the sight of oil-soaked survivors silently trudging ashore from rescue craft of all shapes and sizes inspiring the best from what these largely isolated peoples had to give.

On Sept. 7, the eventual ace of the St. Lawrence campaign, Kapitänleutnant Paul Hartwig of U-517, commanding his first and only war patrol, sunk three merchant ships off Cape Gaspé—Mount Pindus, Oakton and Mount Taygetus, killing seven. He would leave the gulf about two months later with nine ships to his credit.

Many of the 78 survivors who made it ashore ahead of the detritus of their sunken vessels late that Labour Day afternoon were carted off by truck or horse-drawn wagon to the Kruse Hotel in the town of Gaspé, where they came under the care of Rachel Kruse, by all accounts a force of nature whose husband Alfred, a thriving businessman, had died in 1936.

Hotelier Rachel Kruse poses with survivors after U-517 sank three ships off Cape Gaspé, Que., in September 1942.[Firefly Books]

U-boat strikes had become almost a familiar, though dreaded, part of life.

She was known far and wide as “The Fighting Lady” and her hotel had become a centre of the small community, where music and drink flowed freely—at least until the piano player, a sailor, shipped out, never to be heard from again.

At the first sign of her latest round of not-wholly unexpected guests (the hotel had been commandeered by the government on their behalf), Kruse took to the large cardboard box filled with second-hand clothes she kept squirrelled away for just such circumstances.

She matched garments to each person’s needs, give or take a size or two. Hotel guests, primarily long-term residents working at the nearby Fort Ramsay naval station, gave up their beds for the arrivals, many of them blackened by oil and shivering from the frigid waters.

The overflow slept on the floor. In one case, a guest returned after hours and crawled sleepily into bed, only to find it occupied by a Greek merchantman.

The next day, they were gone, the story all but lost to time, the censored newspaper accounts of the day imparting the bare facts and not much else.

“No one in Canada would know of the unexpected guests who arrived in the night,” navy veteran James W. Essex wrote in his 1984 book, Victory in the St. Lawrence. “Someone would snap a picture of Mrs. Kruse by the early light of the following morning as she bade farewell to the men she had helped before they were whisked away by special train.

“This picture was proudly displayed by her son Earl on the wall of his home: it showed ‘The Fighting Lady’ surrounded by the men she befriended, their ill-fitting clothes a testimony to her determination and charity, but it was never reproduced in any newspaper, anywhere.”

After Hartwig sank the Canadian corvette Charlottetown off Cap-Chat, Que., four days later, killing 10 of 64 crew, Dorothy German laid the wounded on her living-room floor in Gaspé—“like cordwood,” as Essex described it.

At one point, a steward appeared in the entranceway and dryly observed that their oil- and blood-soaked bodies would spoil the carpet. German kept on with her task.

“Those who were in the water when the depth charges let go were the worst off,” Essex wrote. “The concussion bursts the blood vessels and you die a slow death.

“Retching and coughing blood are the unmistakeable signs.”

Men hold the remains of the torpedo that destroyed Scotia Pier at Bell Island, Nfld., on Nov. 2, 1942 [LAC/3516152]

The war, therefore, was very much present in the hearts and minds of those who were there, and among Newfoundlanders generally.

German’s husband, auxiliary Captain Barry German, a First World War veteran who was then serving as naval officer in charge of Fort Ramsay and commanding the auxiliary fleet at Gaspé, soon arrived. He knew the signs, all right.

He took one look at the mass of wounded and ordered them all taken to the local hospital, where some died. Most of those who recovered would have been reassigned to other merchant ships, some to survive other sinkings—or not.

In Conception Bay on Newfoundland’s east coast, U-boats sunk five cargo ships at Bell Island in September and November 1942, several of them loaded with iron ore from the island’s mines northeast of St. John’s. Sixty-nine merchant seamen died.

Local residents witnessed the strikes at the anchorage just off the island. An errant torpedo blew up one of the main wharves. During the action, residents took to boats, rescuing the survivors and collecting the dead.

The war, therefore, was very much present in the hearts and minds of those who were there, and among Newfoundlanders generally. They were a people, after all, whose primary vocation was spent on the sea, and at least seven Atlantic fishing schooners had been sunk by German U-boats, both near and far from home.

On May 7-8, 1942, U-136 sank the Sydney-based fishing schooner Mildred Pauline, captained by Newfoundlander Abraham Thornhill, off Nova Scotia. Thornhill’s 21-year-old son George was among the seven-man crew. All were lost.

U-boats dispatched Newfoundland-owned freighters with Newfoundland crews, including the Humber Arm and the Waterton, both owned by Bowaters Newfoundland Pulp and Paper in Corner Brook, and several vessels belonging to the St. John’s-based Anglo-Newfoundland Development Company.

In the former dominion’s justice department files are censored excerpts from letters by Newfoundlanders, many written with such events fresh in their minds.

In a letter to former school chum Kay Normore in England, Doris Higgins of Wabana, Nfld., cryptically describes the aftermath of the second Bell Island attack the previous Monday and how the doctor fetched her father at 4 a.m., telling him to “hurry up for God’s sake and get the van and go and pick up the wounded.

“He was already out of bed because we were already awakened, and so was everyone else on Bell Island who had ears,” she said, describing the “impressive and sorrowful sight” of 11 funerals making their way through town a few days later.

She discouraged Normore from coming home “by water.”

“It’s too dangerous,” Higgins wrote, “and Kay, my love, we people around here should know that.”

In the end, the Battle of the St. Lawrence was neither won nor lost. By the fall of 1944, German U-boats had simply left the gulf behind for richer Atlantic waters.

Little known in the rest of the country today, the extraordinary events of 1942 still resonate among Atlantic Canadians through stories, memorials and tombstones; memories, myths and legends.

Advertisement