The weapons of choice in these drone-on-drone battles are not bullets, missiles or bombs, but in many cases cheap, hobby-quality quadcopters and the like, for which altitude and blunt force have proven the great equalizers in aerial duels with more sophisticated, and expensive, hardware.

“This is something we haven’t seen before,” Caitlin Lee of the Center for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Autonomy Studies in Arlington, Va., told Scientific American. “This is the first time we’re seeing drone-on-drone conflict.”

Operated by pilots at a safe distance—Canada and the United States have conducted drone operations from halfway around the world—the aircraft known in military parlance as UAVs (unmanned aerial vehicles) have changed the face of war in recent decades.

Some, like Teledyne Flir’s Black Hornet, are as small as a dragonfly; others, such as the 14-metre-long RQ-4 Global Hawk with its 40-metre wingspan, are as big as a good-sized plane. No matter the size, however, all have given those on the ground, whether military or civilian, ample reason to keep an eye skyward in times of war.

Ukraine’s military have famously and effectively used drones—notably Turkey’s bargain-priced Bayraktar TB2—in opposing the Russian invasion launched in February 2022

Having played a major role in turning what Vladimir Putin declared would be a three-day “special operation” into a 14-month-long Russian bloodbath, the Bayraktar has reached legend status in Ukraine, where babies, even a lemur at the Kyiv Zoo, have been named after it and a folk song boasts that it “makes ghosts out of Russian bandits.”

American and European allies have also donated strike and observation drones to Ukraine, including the Switchblade, a U.S. munition that hovers over a battlefield until a tank or other target comes into view, then dives down to blow it up.

They have experimented with 3D-printed materials and coders have come up with workarounds for electronic countermeasures the Russians use to track radio signals.

The maker of the fixed-wing Punisher, a high-end military drone manufactured in Ukraine, charges people US$30 to send a written message on the bombs it drops.

But the convoy of armoured vehicles and supply trucks ground to a halt within days, and the offensive failed, in significant part because of a series of night ambushes carried out by a team of 30 Ukrainian special forces and drone operators on quad bikes, a Ukrainian commander told The Guardian last year.

The drone operators were drawn from an air reconnaissance unit, Aerorozvidka, which began eight years ago as a group of volunteer tech specialists and hobbyists designing their own machines. It evolved into an essential element in Ukraine’s successful David-and-Goliath defence against the Russian aggressors.

For their part, the Russians have been relatively slow on the uptake.

“If launched in bunches, as the Russians have been doing, enough are able to evade even the best defenses to do substantial damage.”

The war was months old by the time Moscow employed the Iranian-built Shahed-136 drone. Small, cheap, relatively slow-moving and carrying far less punch than conventional weapons, the Shaheds have, as Black Hawk Down author Mark Bowden wrote in The Atlantic, “bedeviled Ukraine’s otherwise excellent air defenses.”

“Preprogrammed with a target and released in groups of five, the triangular, propeller-driven drones are relatively easy to destroy—if you can find them,” said Bowden. “They fly low and slow enough to be mistaken on radar for migrating birds.

“If launched in bunches, as the Russians have been doing, enough are able to evade even the best defenses to do substantial damage.”

Ukraine estimated in October that it was shooting down at least 70 per cent of the Shaheds, but the ones they missed were enough to debilitate the nation’s electrical grid. Russia has launched hundreds since last August.

“In the last two weeks, we have been convinced once again the wars of the future will be about maximum drones and minimal humans,” Ukrainian Vice Prime Minister Mykhailo Fedorov said in November 2022.

Widely available and affordable in large numbers, they may not be capable of mass destruction, but the potentially vulnerable targets are nearly infinite.

Bowden described future battlefields overrun by the so-called drone swarm, a large cluster of small flying machines that will “herald a new era of intelligent warfare.”

“Thousands of robotic aircraft no bigger than a starling would be all but invisible when spread out, yet capable of instantly coalescing into a swirling dark cloud, like a murmuration. It would move the way such phenomena move in nature, guided by a kind of group intellect.”

A swarm is an intelligent organism and an intelligent mechanism, Samuel Bendett, an expert in Russian weapons at the Center for Naval Analyses, told Bowden.

“In a swarm—just like in an insect swarm, in a bird swarm, in a school of fish—each drone thinks for itself, communicates with the others, and shares information about its position in a swarm, the environment that the swarm is in, potential threats coming at the swarm, and what to do about it, especially when it comes to changes in direction or changes in swarm composition.”

Military planners are already looking at employing combat drones armed to fight in tandem with piloted aircraft. The U.S. Air Force, for one, envisions a fleet of 1,000 high-performance UAVs paired with its most advanced combat jets.

With the escalation of drone attacks in Ukraine, early dogfights sprung from the proliferation of commercially available, low-cost, low-altitude aircraft, such as made-in-China quadcopters, easily modified hobbyist contraptions that can conduct overhead surveillance and drop grenades.

Stopping them is harder than it might appear. Since they are not much bigger in diameter than a large pizza and most weigh less than half a kilogram, they are hard to detect.

“We can retrain air defenses to look for smaller radar cross sections, but then they’ll pick up every bird that flies by,” Sarah Kreps, director of the Cornell Brooks School Tech Policy Institute, told Sherman.

She likened them to improvised explosive devices—they’re far less expensive or sophisticated than the systems militaries had been trained to destroy.

Widely available and affordable in large numbers, they may not be capable of mass destruction, but the potentially vulnerable targets are nearly infinite, enabling a group with fewer resources to attack a more powerful foe.

As an instrument of terror, armed drones could easily infiltrate city skies and threaten such things as crowd safety at major sporting events, prison security and critical infrastructure.

Soldiers say drones have almost completely replaced reconnaissance patrols and are used daily to drop ordnance.

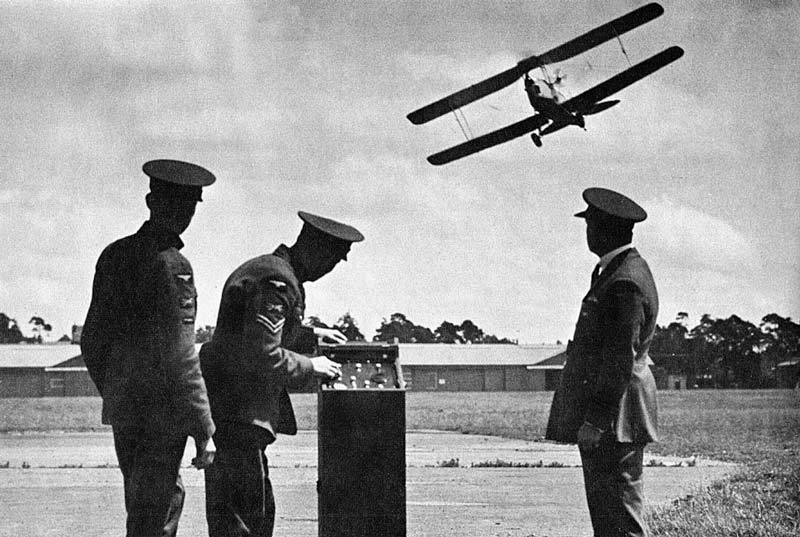

The earliest pilotless vehicles were developed in Britain and the United States during the First World War.

Britain’s Aerial Target, a small radio-controlled aircraft, was first tested in March 1917 while the American aerial torpedo known as the Kettering Bug was launched in October 1918. Both showed promise but neither was used in combat.

Development and testing of unmanned aircraft continued between the wars.

Both the British and Americans produced radio-controlled aircraft for training targets. The Imperial War Museums says the term “drone” is believed to have been inspired by the 1935 de Havilland DH.82B Queen Bee, a remote-controlled plane used for anti-aircraft gunnery training.

Reconnaissance UAVs were first deployed on a large scale in the Vietnam War. Drones also began to be used in a range of new roles, such as acting as decoys in combat, launching missiles against fixed targets and dropping leaflets for psychological operations.

After the Vietnam War, research into unmanned aerial technology spread; endurance and flight ceilings were increased. In 2016, French special operations forces deployed in Syria were among the first to encounter small commercial drones weaponized by attacking Islamic State fighters.

“Less-funded countries now have access to airpower where they wouldn’t have in the past, so that’s changing who’s entering the fray,” said Nicole Thomas, division chief for strategy at the Pentagon’s Joint Counter-Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems Office, which synchronizes the U.S. military’s response to such threats.

More recent developments include technology such as solar power to tackle the problem of fuelling longer flights.

In Ukraine, drones are ubiquitous, believed to outnumber Russia’s arsenal of unmanned aircraft. Soldiers say drones have almost completely replaced reconnaissance patrols and are used daily to drop ordnance.

With the success of Russia’s Lancet-3 kamikaze drones targeting its artillery systems, Ukraine has developed camouflage netting and wire cages that literally snare plunging drones short of their targets.

The U.S. Congress has directed the Pentagon to plan development of defence systems to counter small drones. The market for such systems—both military and otherwise—is expected to grow from about US$2.3 billion in 2023 to $12.6 billion by 2030, according to one private research firm.

More than a dozen companies worldwide are currently developing anti-drone technologies. Utah-based Fortem Technologies has adapted its miniature radar systems to detect small drones. It developed the DroneHunter F70, a drone equipped with two “net heads” that can precisely fire webs to capture their adversaries and bring larger ones down by parachute.

Ukraine first deployed DroneHunters in May 2022 to chase down drones Russia was using to spy on front-line Ukrainian troops.

Advertisement