In nearly two and a half centuries, the United States has recognized outstanding civilian achievements with the Congressional Gold Medal. It is a rare honour; just over 150 have been awarded to groups or individuals since 1776. Of those, just 31 have been struck for non-American individuals, including one Canadian—diplomat Ken Taylor.

By secretly hiding six American diplomats for nearly three months and enabling their escape from Iran on Jan. 27, 1980, Ambassador Taylor and Canadian embassy staff delivered one bright moment during the 444 days of the Iran Hostage Crisis.

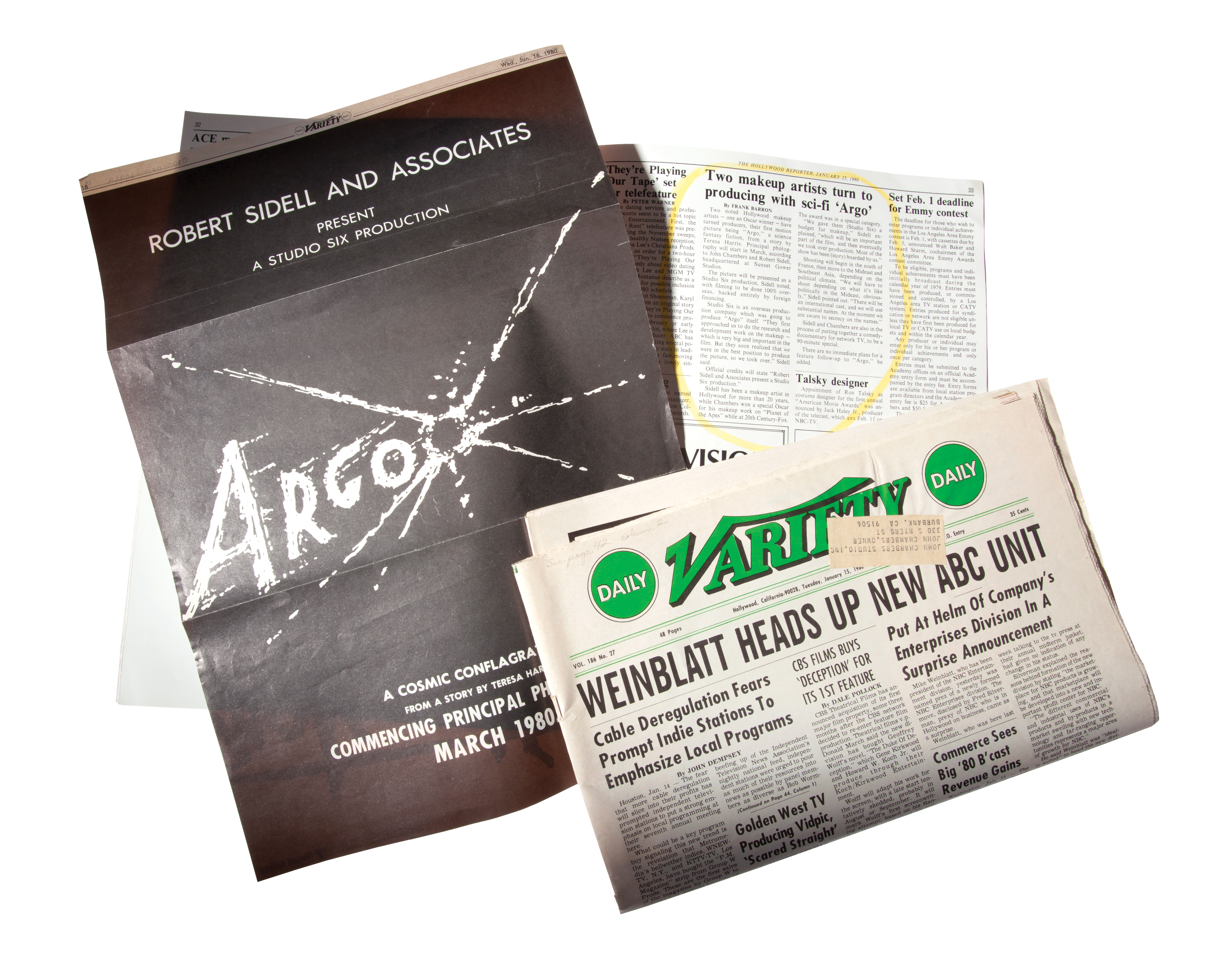

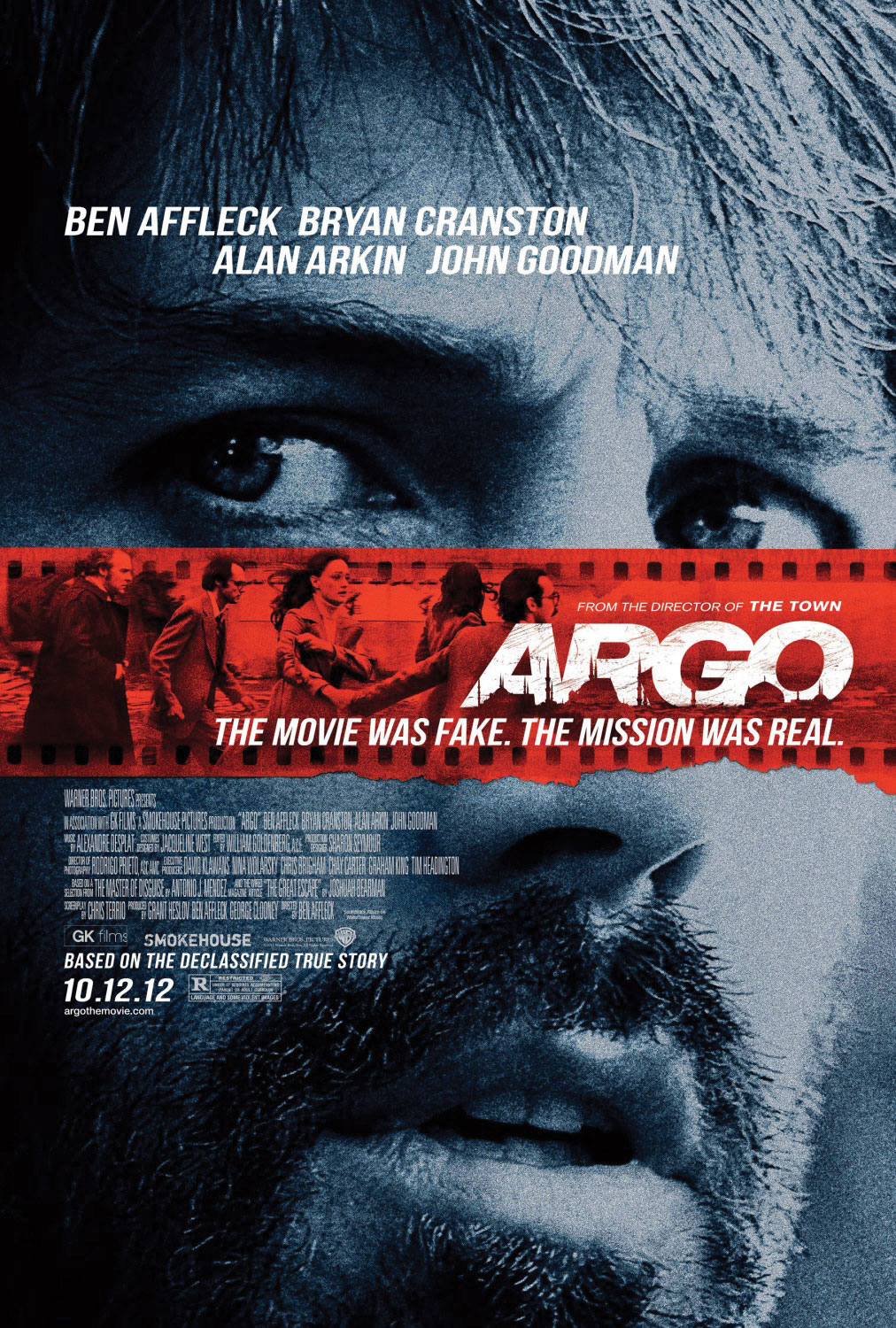

The ruse involved a fake film company called Studio Six Productions making a fake movie titled Argo. Accompanying materials included an ad and article in Variety. [CIA Museum]

In January 1979, U.S.-backed Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi fled the growing violence of the Iranian Revolution. In October, he went from Egypt to the U.S. for cancer treatment. Militant students demanding his extradition seized the U.S. embassy in Tehran on Nov. 4, 1979, capturing nearly 70 hostages.

Female, African-American and ill hostages were let go, but the Revolutionary Council refused to negotiate with President Jimmy Carter for release of the remaining 52 hostages.

As U.S. fear and anger intensified, six Americans who had avoided capture were secretly sheltered in the homes of Canadian diplomats John and Zena Sheardown and Taylor and his wife Pat. The Canadians “were committed to keeping us until the crisis ended or until they could get us out,” said U.S. diplomat Mark Lijek.

It was risky—discovery would endanger the lives of all Canadians and Americans in Iran, including the hostages.

Prime Minister Joe Clark’s cabinet secretly authorized the creation of fake Canadian passports. Canada arranged for wallet documents—drivers’ licences, credit cards and other identification, as well as false travel documents.

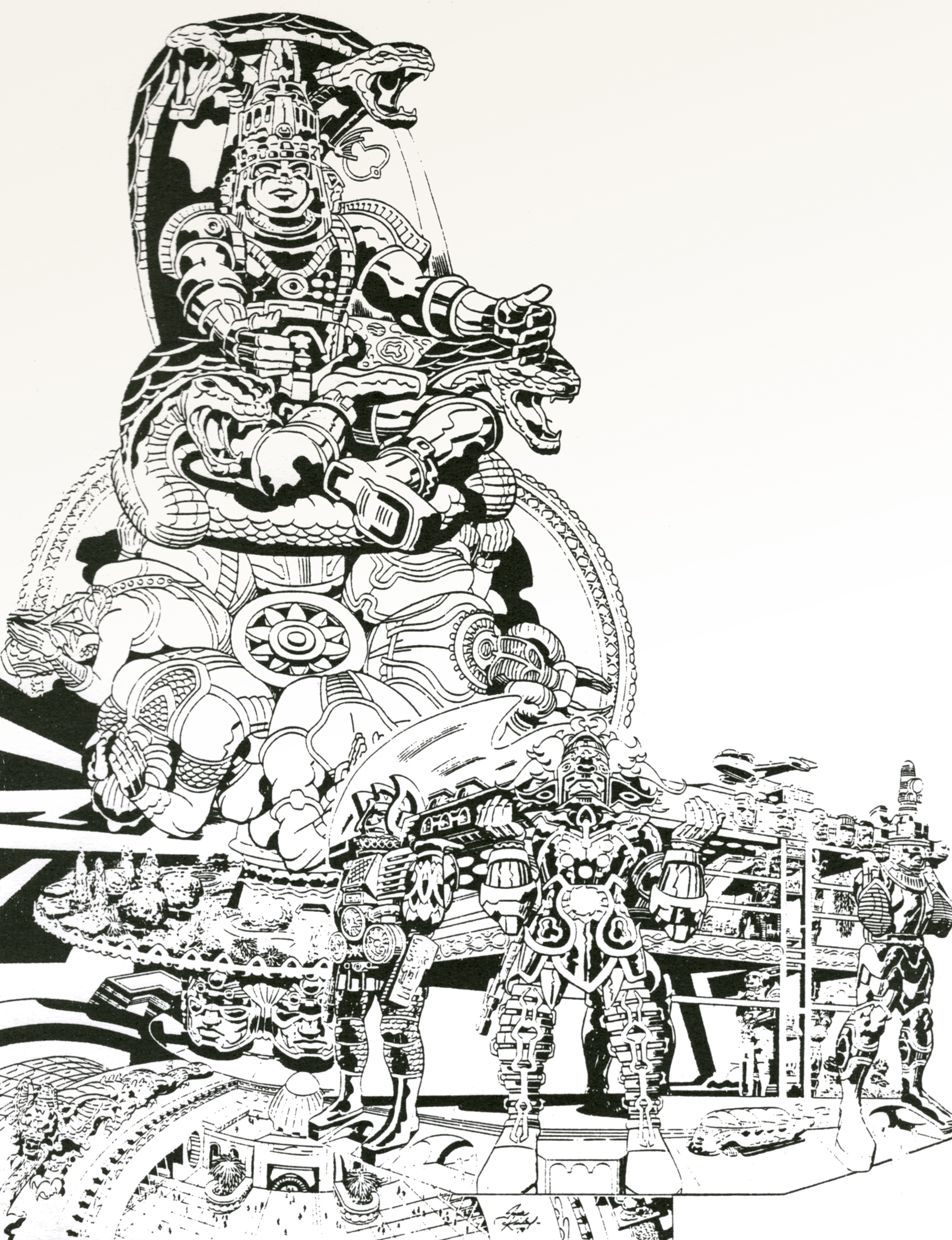

An artist’s concept for Argo. [CIA Museum]

Meanwhile, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency devised an exit cover story: the six were Canadians working for Studio Six Productions in Hollywood and were looking for locations in Iran for a science-fiction thriller, Argo. An office was staffed in Hollywood, ads were bought in trade publications promoting the movie, and business cards were printed.

CIA agent Tony Mendez, who arrived a day and a half before departure to provide escape kits and escort the Americans out, praised Taylor’s “penchant for clandestine planning.” CIA involvement was kept secret, in fear of retribution against hostages.

The planning paid off: the escape went without a hitch at the Mehrabad International Airport in Tehran.

Stationery paper used for the rouse. [CIA Museum]

Americans “went wild” after the story broke, Mendez writes on the CIA website. “It was the first good news after three months of national trauma.” The maple leaf flew in towns and cities across the country, thanks appeared on billboards and in newspaper ads.

But the Canadian caper was a brief respite. Tension ballooned after a botched rescue mission that claimed eight U.S. military personnel and one Iranian.

U.S. frustration spilled out in violent actions, dubbed ‘I-rage.’ The wife of one hostage urged people instead to more peaceful support. A newspaper reported that she had tied a yellow ribbon around an oak tree in her yard, and soon such ribbons appeared across the nation. The symbol spread to pins, bumper stickers, billboards and clothing. Such ribbons have since become a symbol of hope and support for those in threatening situations.

Although the Shah died in Egypt in July 1980, the hostages were not released until minutes after the 1981 inauguration of President Ronald Reagan, who credited Taylor’s “valor, ingenuity and steady nerves” when he presented the award that June.

Taylor was made an officer of the Order of Canada. Other Canadians were made members of the order and three Canadian military members received the Order of Military Merit.

Sheardown died in 2012. Taylor, hailed in 2013 by President Jimmy Carter as “the main hero” of the covert operation, died in 2015.

Top Photo: The United States Congressional Gold Medal—the country’s highest expression of national appreciation—is cast with the likeness of the honoured individual. Ken Taylor received his in 1980.

Advertisement