In moonless nights, silent as clouds, Zeppelins floated over Britain, the original stealth bombers, raining destruction on military targets and unsuspecting civilians. They flew so high it took planes of the day an hour to climb to their height, and when they got there, their bullets just poked holes in the air bags.

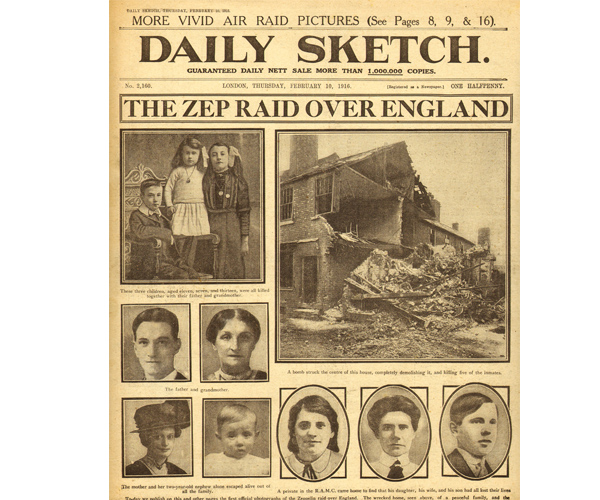

Initially, Germany’s First World War airships provoked helpless outrage.

Zeppelin crews called themselves Knights of the Air; the British called them baby killers.

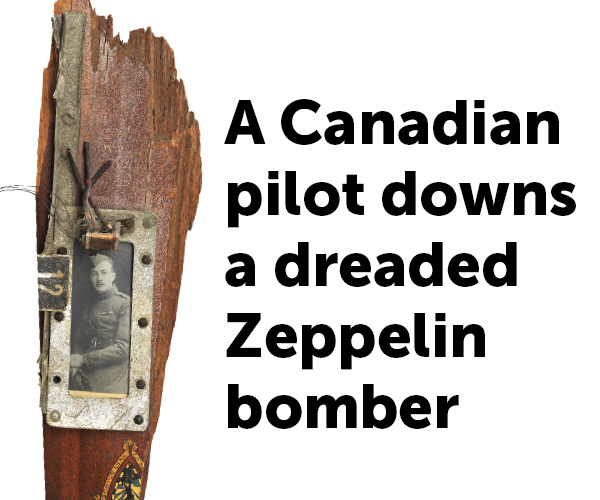

A photo of Wulstan Tempest is mounted with pieces from the L-31 Zeppelin on a fragment of his plane’s propeller. [CWM/19650080-001]

High-altitude bombing by the German navy’s Zeppelins and the army’s Schütte-Lanz airships was meant not only to damage factories, but to sap the Allies’ will for war. The second goal went unmet, but Zeppelin raids destroyed an estimated one-sixth of British munitions output to 1916.

But by the fall of 1916, Britain was no longer in thrall to Zeppelins. Remote listening stations warned of attacks, and a network of searchlights illuminated airships for anti-aircraft guns and fighter planes that were armed with explosive bullets that could ignite the hydrogen gas that kept them aloft. Planes patrolled all night at the right altitude to intercept. Sixty of the 84 Zeppelins built during the war were lost, half shot down. Perhaps the most significant was the L31.

A 1916 postcard captures the demise of a dreaded airship. [E.A. Munday]

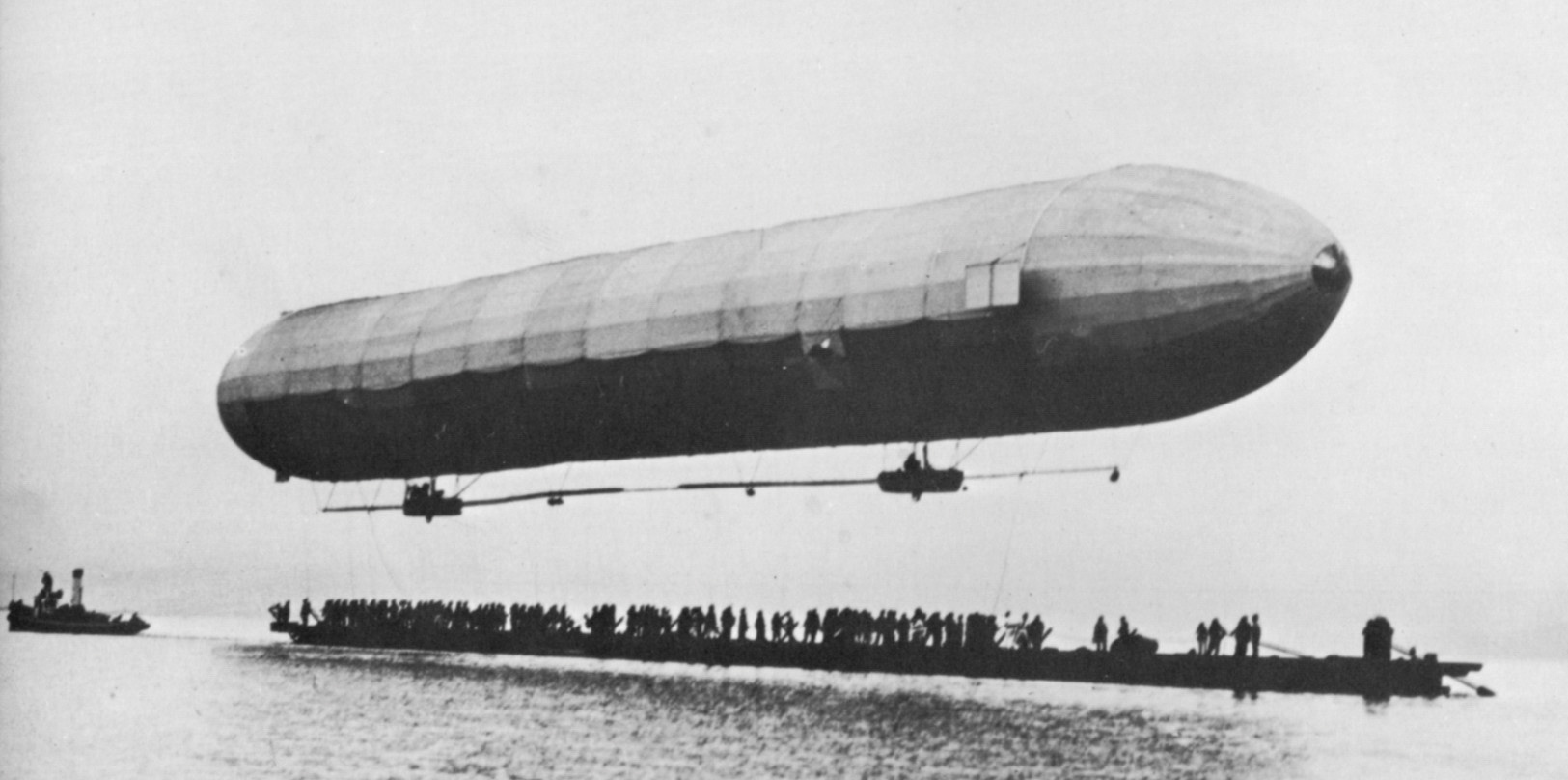

At 227 metres long and 24 metres wide, L31 was bigger than a battleship. Its 19 gas bags contained 57,000 cubic metres of hydrogen, a gas so explosive crews wore felt boots to prevent static electricity. The ship was equipped with machine guns for defence and carried dozens of incendiary bombs. It had a crew of 19, and was piloted by ace Heinrich Mathy.

“It seems the Zeppelin is in the zenith

of the night, golden like a moon,

having taken control of the sky.”

– D.H. Lawrence

On Oct. 1, 1916, L31 was the only one of 11 raiders to make it to England. It was Mathy’s 15th raid. He cut his engines and attempted to drift silently over London’s wary gun defences. When he turned the engines on at about 11:30 p.m., he was immediately spotted, lit by searchlights, then targeted by anti-aircraft guns and fighter pilot Second Lieutenant Wulstan Tempest.

The wreckage of Mathy’s Zeppelin scattered across a field at Potters Bar. [Wikimedia Commons]

Tempest and his brother Edmund were immigrants who were farming in Saskatchewan, but returned to England when war broke out. Both became Royal Flying Corps pilots. On this night, Tempest was at the controls of a Bleriot Experimental craft, pumping fuel by hand due to a malfunction. It took him about 20 minutes to reach the Zeppelin, which had jettisoned its bombs and was climbing to a safer height. Though peppered by machine-gun fire, Tempest raked the Zeppelin’s length with incendiary bullets. “I saw her begin to go red inside like an enormous Chinese lantern,” he said. Tempest went into a nosedive, corkscrewing to avoid the flaming hulk as it plunged towards earth.

With no parachutes aboard L31, the crew faced a terrible choice: burn or jump. Mathy jumped.

The Zeppelin crashed just north of London at Potters Bar; Mathy landed nearby, leaving a deep impression in a farmer’s field. Tempest crash landed, fracturing his skull.

Michael MacDonagh reported “a shout of mingled execration, triumph and joy…rising from all parts of the metropolis, ever increasing in force and intensity” from the thousands watching the Zeppelin’s demise.

After this, Zeppelin raids diminished. The German army lost confidence and concentrated on developing fixed-wing aircraft, said historian John Maker of the Canadian War Museum.

A German incendiary bomb dropped on London during an airship attack. [Wikimedia commons]

Tempest’s ground crew fashioned a memento from his splintered propeller. Tempest was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and later flew 34 bombing missions, earning the Military Cross.

By the numbers

1900

first Zeppelin flight

5,900+

Zeppelin bombs dropped

on Britain

500+

Britons killed

by Zeppelins

50+

Zeppelin raids 1914-18

4

number of

raids in 1918

The first Zeppelin launched in southern Germany in 1900 carried passengers, but during the war, airships carried a deadly cargo. [IWM/Q55554]

Advertisement