A view of the French village of Loos from a crater on Hill 70, where Harry Atherton was killed in action on Aug. 15, 1917. His fate was unknown until combat engineers clearing First World War munitions stumbled on the remains of a Canadian soldier. Authorities confirmed his identity in October 2021[Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

Captain Scott McDowell was just a young boy, eight or 10 years old, when he first heard the name Percy Bousfield, a great-great-uncle who went to sea at 14, sailed the world, then joined the army and died on the Western Front in 1916.

The remains of Corporal Bousfield, a 20-year-old signaller with the 43rd Battalion (Cameron Highlanders of Canada), were not accounted for, his last resting place unknown. But his legend lived on in family lore.

His maternal grandmother was a Bousefield and McDowell heard the stories many times growing up, though he never knew investigators were searching for his relative. Or that he was an unknown soldier, his name among more than 54,000 missing British and Empire combatants listed on the Menin Gate memorial in Ypres, Belgium.

A career military intelligence officer, McDowell happened to have transferred to the Canadian Forces’ Directorate of History and Heritage as a war diaries officer in August 2022, working in a nondescript brick building in Ottawa. Three months later, he and his colleagues were summoned to an all-hands town hall. It was during the meeting that senior staff coincidentally announced an investigation team had identified the grave of Corporal Frederick Percival Bousfield.

“The world stopped spinning for a moment,” McDowell told Legion Magazine. “I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, that’s Percy.’ I was gobsmacked. The odds of it are effectively zero. It’s completely insane. I didn’t hear a single word the rest of the town hall.”

Corporal Frederick Percival Bousfield

Bousfield was killed at Mount Sorrel in Belgium on June 7, 1916. The hill in the Ypres Salient was taken from the Canadians, then recaptured during two weeks of intense fighting. Allied units sustained 8,430 casualties in 12 days.

“At the time he was off duty, but he was not content to be idle and despite the terrible hurricane of shells he was doing magnificent work in helping our wounded,” his one-time company captain, Horace John Ford, wrote Bousfield’s mother.

[Marjorie Bousfield/Bousfield family archive (5); Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

“It was while lifting one of his helpless comrades that a shell burst right at his feet, so you see that brave lad experienced no pain whatever, and although his death is a grievous pain to his loved ones, yet they can glory and thank God for the manner of it. He was doing humane work to relieve suffering and doing it nobly and well and without fear or thought of reward.”

“The world stopped spinning for a moment. The odds of it are effectively zero. It’s completely insane.”

English by birth, Bousfield’s remains were buried in a temporary grave alongside others behind a cottage near the church in Zillebeke not far from where he died. It was marked by a simple wooden cross, which would be replaced by one of the now-familiar pale white or grey tombstones that adorn British and Empire war plots once the battlefield graves were relocated.

Thousands of similar temporary plots were hurriedly created on or near First World War battlefields. Given the stagnant nature of the fighting, they were often trodden over repeatedly, damaged by shellfire and flooded by rains. Many were overrun, first by advancing enemy and later by the Allies pushing eastward again. Plots were inevitably destroyed, and the locations of many registered and otherwise documented graves were obliterated.

[Marjorie Bousfield/Bousfield family archive (5); Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

So it was with Bousfield’s remains.

On Sept. 14, 1923, a headstone at Bedford House Cemetery, near Ypres, was recorded as “A Corporal of the Great War—Canadian Scottish—Known Unto God.” The remains had been transferred with others from Zillebeke the previous February. They were not identified, the date of death unknown, although the other graves were confirmed as Mount Sorrel casualties.

“I regret to have to inform you that although the neighbourhood South-East of Ypres, in which Corporal F. P. Bonsfield [sic] was reported to have been buried has been searched, and the remains of all those soldiers buried in isolated and scattered graves reverently reburied in cemeteries in order that the graves may be permanently and suitably maintained, the grave of this soldier has not been identified,” said a 1927 letter from what was then called the Imperial War Graves Commission, later the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

And so, Percy Bousfield was lost, but not to memory. For a 20-year-old of his time, he had lived an incredibly full and well-documented life and, for almost a century after, pictures, letters and tales of his adventures and his noble death circulated among his family.

Then in October 2019, the History and Heritage Directorate received a report from the commission detailing the potential identification of Grave 68, Row C, Plot 11 in Enclosure No. 4 at Bedford House.

The commission, which manages more than 1.1 million war graves in over 23,000 locations in 150 countries and territories, had received three “very in-depth reports” from independent researchers suggesting the grave was that of Corporal Frederick Percival Bousfield.

Frederick Bousfield’s memory has lived on in family lore. Pictures, postcards, letters and souvenirs from the former seaman are plentiful. Bousfield was sailing the world when his family immigrated to Canada from England in 1912 and settled in Winnipeg.[Marjorie Bousfield/Bousfield family archive (5); Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

The directorate launched its own investigation involving the Canadian Forces Casualty Identification Program, the Forensic Odontology Response Team and the Canadian Museum of History.

They reviewed war diaries, service records, casualty registers and grave exhumation and relocation reports. They concluded the grave could only be that of Corporal Bousfield. No other candidate matched the details of the partial identification.

Renée Davis is a civilian historian at History and Heritage and a principal researcher for the Casualty Identification Program. She and a small team of historians and co-op students conduct the research and analysis of graves cases, which differ significantly from the identification of found remains.

“Usually this is a headstone for an unknown, but for whatever reason there is a unit identifier or a date of death or anything along those lines that sparks [an independent researcher’s] interest,” she explained in an interview.

“And so, they start doing a bit of research and submit a report to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.”

Frederick Bousfield’s memory has lived on in family lore. Pictures, postcards, letters and souvenirs from the former seaman are plentiful. Bousfield was sailing the world when his family immigrated to Canada from England in 1912 and settled in Winnipeg.[Marjorie Bousfield/Bousfield family archive (5); Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

And so, Percy Bousfield was lost, but not to memory. For almost a century after, tales of his noble death circulated among his family.

The commission then conducts a preliminary analysis into the merits of each case and submits a report to the country involved, including the independent researcher’s findings, as well as their own, along with its recommendations.

It’s at this stage that Davis’s team steps in. They investigate and write the reports, making recommendations to Canada’s Casualty Identification Review Board on whether to positively identify gravestones. They do not conduct exhumations.

Davis said her team is able to positively identify two in 10 headstones that are brought to their attention. Eleven of the 46 identifications they’ve made so far were from grave markers, the rest from remains. The vast majority are First World War, in which there were a far greater proportion of missing in action than in WW II.

At this writing, the Casualty Identification Program had 40 active investigations involving remains and 38 involving graves.

“You feel very connected to these individuals in a very tangible way,” said Davis. “Sometimes the cases work out, like this one, and you feel absolutely wonderful.

“But other times, more often, there’s not enough to definitively say it is this person, and that can get a little gut-wrenching at times.”

No other candidate’s profile matched the sparse details of Bousfield’s.

“The family was so fortunate that Percy was a corporal because his stone identified him as a corporal, Canadian, and the records said he was with a Highland regiment,” said the family historian, McDowell’s second-cousin Marjorie Bousfield. “So that really narrowed it down.

“If it had just said ‘Unknown Soldier,’ there’s no hope because there are so many. In Percy’s cemetery at Bedford House, there are [5,139 Commonwealth] graves, of which [3,011] are unidentified.

“It’s staggering. It’s really staggering.”

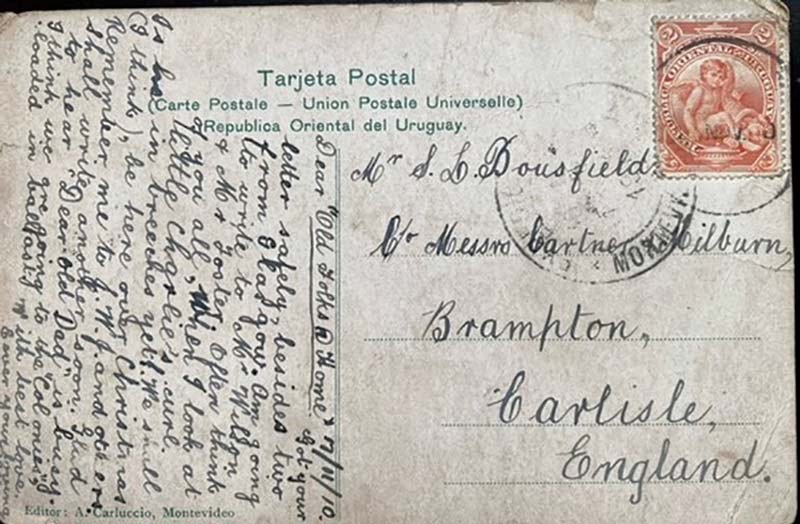

A postcard Bousfield wrote to his parents as a 14-year-old seaman in 1910. [Marjorie Bousfield/Bousfield family archive; Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

Marjorie Bousfield had traced her great-uncle’s life through his years as a seaman, interviewing his siblings, tracking the ships on which he had sailed and the far-flung places he had visited, uncovering the pictures he had drawn (he was a sketch artist) and the letters and postcards he had written.

The family, she said, “had no idea that he was there” in the cemetery at Bedford House until the day McDowell sat down for the town hall at History and Heritage.

“I’m so sad that he never got to fully live his life,” she said. “And then the sadness increases because you multiply that by all those young men in the First World War—just incredible numbers. And you think of the effect it had on family members at home because he was just an absolutely loved brother.

“And, for me, I feel happy. We’re not like families nowadays. When they get notification from the military, it’s only a really sad story. We already knew the fact of his death, so that sadness and tragedy isn’t there—the immediacy. And so, we can be happy that we know where he is.”

Unlike the missing recorded on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France, which remain unchanged even after one is identified, Bousfield’s name will be removed from the Menin Gate.

Private Harry Atherton

Harry Atherton was just 19 years old when he left the factories, foundries and collieries of his home in Tyldesley, an ancient mill town in the north of England, and came to forge a new life in Canada.

He couldn’t have found a spot much farther away, or much different, from his home, settling as he did in McBride, B.C., a Rocky Mountain village that, even in 2021, numbered just 588 people.

It was 1913, a fortuitous time for a carpenter such as Atherton in a place like McBride.

Far from the Roman road that ran through his hometown where urbanization and industrialization took root in the 19th century, McBride was a new settlement located on Mile 90 of the Grand Trunk Pacific Railway. A train station was being built on what would become Main Street. The area was growing on the strength of agriculture, logging and the railroad.

Atherton, however, would never see much development past the little building with a platform and the sign “McBride.” A year after he arrived, a world war broke out in Europe, a war from which Atherton would never return.

Atherton’s cap badge (opposite left) with the 10th Battalion’s distinctive beaver-and-crown emblem, along with C10 collar badges and a brass Canada shoulder title found with his remains. [DND; Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

In March 1916, Atherton, by then a 23-year-old tradesman, hopped the eastbound train for Edmonton, where he enlisted with the Canadian Expeditionary Force. By July, he was in France fighting on the Western Front with the 10th Canadian Infantry Battalion.

In August, Atherton headed for one of the bloodiest battles of the war, the Somme.

On Sept. 26, 1916, he was shot through the left thigh during the brutal fight for the German fortifications at Thiepval, one of the 10th Battalion’s 241 casualties. As many did in the mud and filth of wartime France, his wound turned septic. Atherton was hospitalized for 72 days before he was allowed to return to duty in March 1917.

It appears he missed the fighting at Vimy Ridge in April, but he was back with the 10th by mid-May and fought at Hill 70 in August. It was there, on the outskirts of the French coal-mining town of Lens, that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps under Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie met five divisions of the German 6th Army. It took 10 days to wrest the chalky hill from German hands.

Canadian and British guns fired almost 800,000 shells in the days before the attack. Advancing under the cover of a smokescreen and a creeping barrage, Canadian infantrymen fired, and faced, millions of machine-gun rounds.

The fighting would eventually come down to close-quarters, hand-to-hand, life-or-death desperation. Six Canadians were awarded Victoria Crosses for individual actions at Hill 70, and all but two involved bloody close-quarters fighting.

Atherton was reported wounded on the battle’s first day. Soon after, word spread that he was dead.

On July 11, 2017, a century after he died, combat engineers clearing old munitions found human remains near rue Léon Droux in Vendin-le-Vieil, north of Lens. They would turn out to be Atherton’s.

What happened to the 24-year-old private and how he disappeared will likely never be definitively known.

“To be honest, I don’t look for that,” said Sarah Lockyer, the forensic anthropologist who analyzed Atherton’s remains and wrote the investigation report. She’s the Canadian military’s casualty identification co-ordinator.

“The remains are stored typically in a location close to where they were discovered,” she said, explaining that she has seven to 14 days to analyze them and the focus is identification, not cause of death.

“So, it’s things that come from the biological profile—age estimation, height estimation, if there is something weird about the teeth or is there like a healed fracture that maybe is in the personnel files and things like that.

“At the end of the day, they were killed in action, so they all died of war.”

Atherton was reported wounded on the battle’s first day. Soon after, word spread that he was dead.

More than 9,000 Canadians were killed, wounded or declared missing in action at Hill 70. The 1,300-plus missing there were among the highest of any Canadian battle of the war. Lockyer said 40 of the 41 sets of the remains her office was analyzing at the time she was interviewed were from the First World War, most from Hill 70. The other set of remains are from WW II.

“There’s a lot of construction going on in that area and the remains are just kind of popping up everywhere,” said Lockyer.

Atherton’s 10th Battalion suffered 429 casualties at Hill 70, 71 of them with no known grave. The dead included one of the six Canadian VCs—Private Harry Brown, who was caught in a counterattack the day after Atherton was killed.

The engineers who found Atherton’s remains also recovered several artifacts, including an identification disc and 10th Battalion insignias—a cap badge with the battalion’s distinctive beaver-and-crown emblem among them.

In time, the Canadian Forces Forensic Odontology Response Team, along with the Canadian Museum of History and the Casualty Identification Review Board, went to work, applying historical, genealogical, anthropological, archeological and DNA analysis to the job.

The partially obscured identification disc yielded confirmation of Atherton’s battalion and service number.[DND; Mary Riter Hamilton/LAC/5067115]

The illegible identification disc, or dog tag, was sent to the Canadian Conservation Institute. After cleaning, “10 BATT” was clearly visible across the bottom. There was also a partial service number, “4 – – 658,” and “ON” was visible near the disc’s upper right border. The soldier’s service number was 467658.

Lockyer said Atherton’s relatives were difficult to track down. He had only one sister, who the anthropologist wasn’t sure had any children. The DNA donor and the next-of-kin were, in fact, two different people, she said.

“They’re both first cousins, four times removed—or something like that. They’re quite far away from Atherton. It happens with his family tree.”

Despite the hurdles, the investigators had confirmed by October 2021 that the remains, indeed, belonged to Atherton. They were buried with two others and full military honours in the Loos British Cemetery in Loos-en-Gohelle, France, this past June.

As is the practice for found Canadian soldiers recovered from French soil, Atherton’s name will remain with 11,285 others on the Vimy memorial.

Advertisement