A painting by John Singer Sargent depicts Allied troops who had been gassed, many with bandages covering their eyes. “Blind Trooper” Lorne Mulloy, [John Singer Sargent/IWM/Wikimedia]

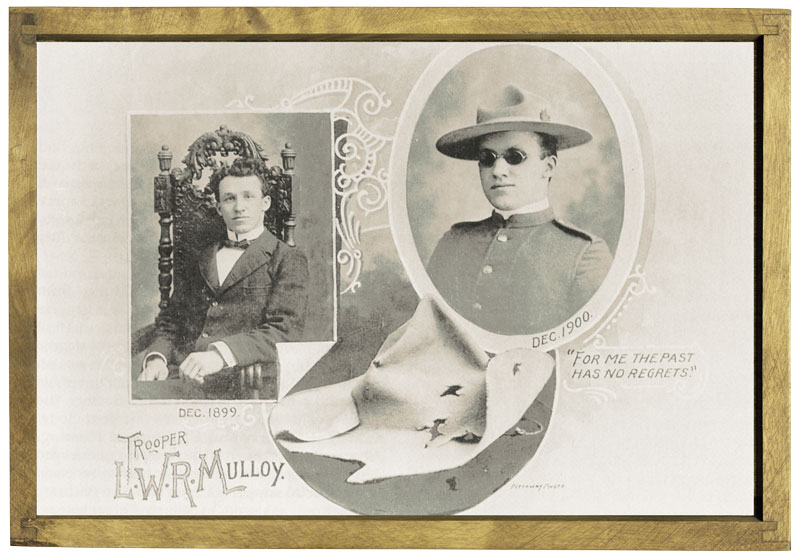

In the early 20th century, Lorne Mulloy was a household name in Canada. In December 1899, Mulloy, then a 24-year-old teacher from Winchester, Ont., volunteered with the Canadian Mounted Rifles during the Boer War. One year later, he was back in Canada a celebrated Imperial and Canadian hero, having been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, the second-highest military decoration for enlisted men behind the Victoria Cross. He had been presented to Queen Victoria and hailed in the press throughout the Empire.

But Mulloy had paid a price: he had been blinded by an enemy bullet. Known as the “Blind Trooper,” Mulloy was Canada’s first war-blinded casualty of the 20th century. His postwar career as a professor of military history at the Royal Military College of Canada, his many speaking engagements and his involvement in public affairs showed what Canada’s war-blinded veterans could achieve. With “self-mastery and self-reliance,” Mulloy wrote, his blindness could be overcome.

But when the First World War broke out in 1914, Canada had no plans for dealing with mass casualties, and certainly none for caring for blinded soldiers. Canada’s first blinded casualty of the war was Lance-Corporal Alexander Viets, of Digby, N.S. While serving with the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry outside Ypres in May 1915, a German mortar bomb exploded beside him, blinding him and inflicting numerous other wounds on his face.

Canada’s first war-blinded casualty of the 20th century.[LAC/C-15081]

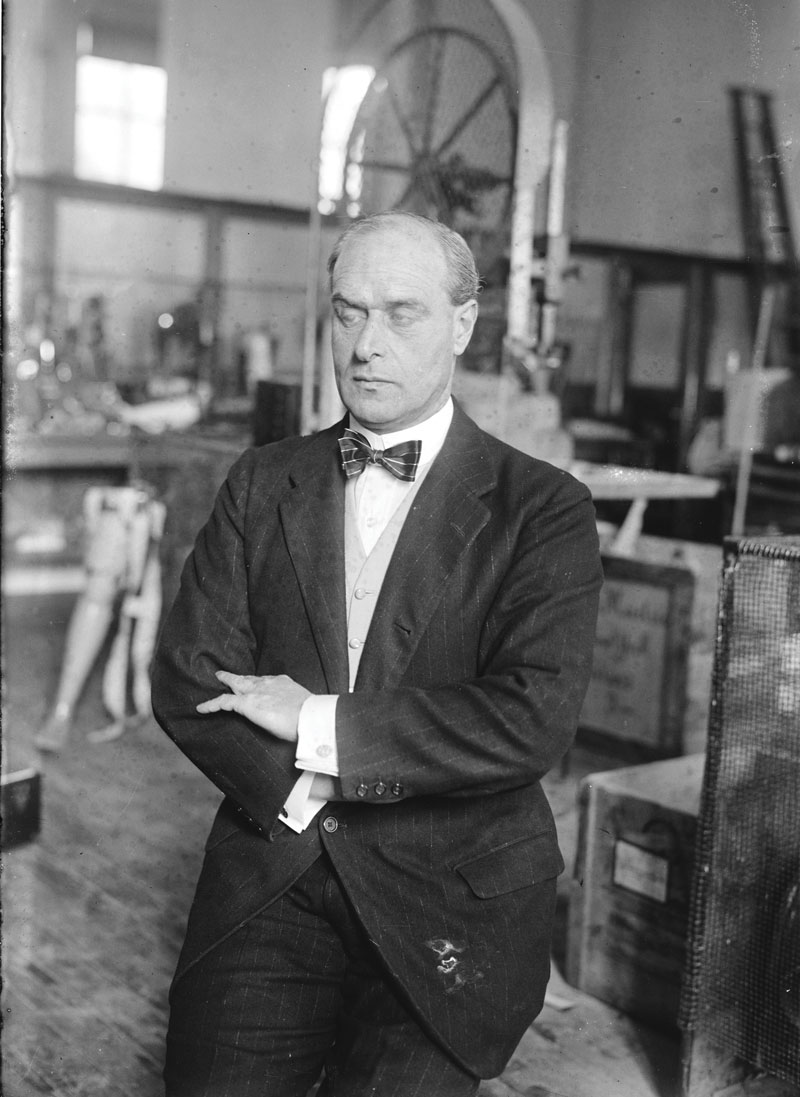

As optical impairments and blindness mounted among British and Canadian troops, plans soon emerged to provide employment training to make them as independent as possible upon discharge. Britain’s National Institute for the Blind offered its services. It was headed by philanthropist Arthur Pearson, a newspaper magnate who had lost his sight.

But Mulloy had paid a price: he had been blinded by an enemy bullet.

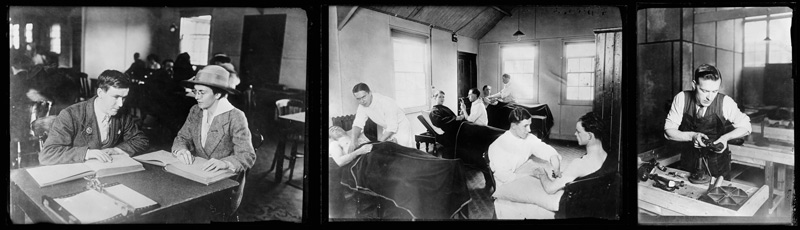

In the early months of the First World War, Pearson established the St. Dunstan’s Hostel for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors with spacious facilities in Regent’s Park, London, in March 1915. It was soon the world’s leading readaptation centre for the blind. The typical occupations of the blinded—broom making and basket weaving—evolved to include more challenging and potentially lucrative skills. The men learned braille and obtained vocational training in cobbling, typewriting, shorthand, poultry farming, rug making and massage, or physio, therapy, the latter a niche occupation for the blind.

Arthur Pearson, blind himself, established the St. Dunstan’s Hostel for Blinded Soldiers and Sailors in London during the early months of the First World War. [Library of Congress/2014708196]

In Canada, there were no such facilities and most of the country’s war-blinded soldiers attended the courses and programs at St. Dunstan’s in London, including those who had returned to Canada before 1918. In March 1916, Viets graduated from the hostel and, by October, he had moved to Toronto and found a job working as an agent for the Imperial Life Assurance Company of Canada. Ultimately, he made it a career.

Their dogged advocacy would lead to breakthroughs in the organization and care of the country’s war blinded.

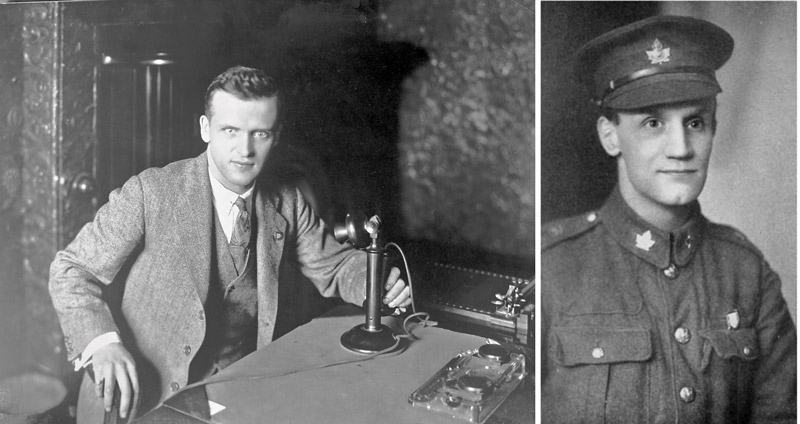

Lieutenant Edwin A. Baker, from Collins Bay, near Kingston, Ont., was one of Canada’s most remarkable First World War veterans. Eventually known to royalty, world statesmen and his veteran comrades, Baker’s international fame was acquired as an eloquent advocate for the blind—and blind veterans in particular.

Baker served overseas with the 6th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers. On the night of October 10-11, 1915, at Kemmel, Belgium, about 10 kilometres south of Ypres, he recalled that sniper’s bullet left him “to the mercy of the darkness.” He was 22.

At St. Dunstan’s, veterans acquire skills such as braille, massage therapy and cobbling.[Library of Congress/2017668790; Library of Congress/2017668800; Library of Congress/2017668784]

In September 1916, Baker graduated from St. Dunstan’s eager to succeed in life and help others overcome similar afflictions. Within a month, he was working in Toronto as a typist. Baker, however, was appalled to discover no government employment opportunities, after-care support or even understanding of the needs of blinded veterans existed in Canada.

Baker and Viets became close friends and combined forces in helping their blinded comrades re-integrate into civilian life and obtain specialized help from Canada’s Military Hospitals Commission and, later, the Board of Pension Commissioners. Their dogged advocacy would lead to breakthroughs in the organization and care of the country’s war blinded.

At St. Dunstan’s, veterans acquire skills such as braille, massage therapy and cobbling.[Library of Congress/2017668785]

The causes of blindness in soldiers included gunshot and shrapnel wounds, as well as optic atrophy caused by poison gas—particularly mustard gas—and detached retinas resulting from the concussive effects of artillery fire.

“I felt a slight sting in my right temple as though pricked by a red-hot needle—and then the world became black,” wrote Private James Rawlinson, who was blinded at Vimy in June 1917. “Night had sealed my eyes.”

Others were blinded by training accidents or disease.

The growing number of blinded veterans pressed Ottawa for a firm commitment to provide better pensions and after-care so that they could live with dignity. In March 1918, the war-blinded veterans and their associates from the Canadian Free Library for the Blind founded the Canadian National Institute for the Blind (CNIB) in Toronto. Baker served as vice-president until 1920, then managing director until 1962, while Viets and a soldier from Saskatchewan, Harris Turner, joined the executive committee.

Blinded Canadian First World War veterans Edwin A. Baker (left) and James Rawlinson (right).[CNIB Foundation; Through St. Dunstan’s to Light ]

The organization’s basic philosophy was to restore independence for the blind. Its first mandate was to provide job and social re-adaptation training under contract to the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment (DSCR). Veterans subsequently received job training, special equipment and even money to travel.

The stigma many Canadians associated with the blind began to change, thanks to how these patriotic men had ennobled the impairment. “If as the result of our blindness the public will become interested in and have sympathy for the civilian blind, the affliction will have been well worthwhile,” remarked one blinded soldier. He believed, too, that the national institute was “a memorial to the gallantry and sacrifices of the Canadian soldiers who have lost their sight in the war.” This heralded a new beginning in the relationship between the sighted and the blind in Canada.

Blinded Canadian veterans pose for a photo while attending St. Dunstan’s. Baker is front row, third from left. [Blind Veterans UK]

In August 1918, Baker was hired by the DSCR to administer policies relating to the ongoing vocational training and after-care of Canada’s war blinded. He met with dozens of blind veterans, assessed their needs and assisted them through their pension applications. But he wanted nothing less than to create a mini version of St. Dunstan’s.

Pearson Hall became the men’s main rehabilitation centre and served as a club where they could socialize with others.

In October 1918, the CNIB leased an elegant home at 186 Beverley Street in downtown Toronto using funds from the department—which purchased it outright the following year for the institute. Fifteen men began their training there immediately, their stays also paid for by the department.

In January 1919, the centre was formally opened by Arthur Pearson, and named Pearson Hall in his honour. The building became the men’s main rehabilitation centre and served as a club where they could socialize with others.

By the war’s end, some 1,347 Canadian soldiers had suffered some form of visual impairment, though only 139 required vocational retraining because of blindness. Due to the discovery of subsequent cases and delayed sight loss, the final tally of blinded Canadians from the First World War approached 200. Half had trained at St. Dunstan’s and many of the remainder at Pearson Hall.

In 1922, blinded veterans formed the Sir Arthur Pearson Club of Blinded Soldiers and Sailors to serve as a lobby group for blinded veterans and as a social organization for comrades who understood each other’s experiences. The club continued to serve the war blinded for almost a century.

“Despite the loss of sight in early manhood and, in many cases, serious additional disabilities,” stated Baker in 1948, “this group of young men has provided an inspiring demonstration…that, despite blindness, the remaining talents can be usefully applied where there is a determined spirit.”

Advertisement