The crisis in Syria and Iraq—and the torment of the refugees—as considered by three of the smartest minds we could find

Syria is dying. It’s emptying out. And the war is unleashing unprecedented chaos on the region, on Europe and on the world.

The New York Times described it as a “proto-world war,” and legendary retired American general David Petraeus described it as “geo-political Chernobyl.” But the question is: what to do about it? Are there any solutions to the refugee crisis in Syria, to the civil war there and to the unending killing perpetrated by Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and by ISIS and by all the other murderous groups?

During the recent Canadian election, our politicians were outdoing each other announcing how they would deal with the symptoms of the crisis, but no one was talking about solutions.

It was as if we were all watching a patient, Syria, bleeding on a table and everyone was debating ways to deal with the blood as it poured out, but no one was attempting any decisive action to treat the wound.

This is the story of trying to find a solution, of trying to find a way to stop the bleeding, by asking some very smart people how it could be done. But here’s the upshot: it probably can’t be done.

Trying our conscience

“There will be senseless deaths that aren’t prevented,” U.S. President Barack Obama told attendees at the Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2012, speaking about Syria. “There will be stories of pain and hardship that test our hopes and try our conscience.”

Here’s what that means: there will be pictures of well-dressed toddlers washed up dead on beaches, images of scared men dragging their elderly mothers across Central Europe, images of millions on the run. Hundreds of thousands killed. Bodies everywhere.

No matter what Obama forewarned, these images don’t fit in the world we know. It feels like they come from another time, maybe an old world war, maybe a future apocalypse.

And these aren’t just pictures, this is reality. These images seem to overcome the usual barrier between Canadians and the faraway world. It’s hard to look at them and not feel tested, not see these scenes of inhumanity and feel like there absolutely must be a better way.

Incrementally, image by image, we’ve gotten to this strange place. Millions have fled the Middle East and the lines of refugees walking across Europe stretch beyond the horizon.

Discussion about these events has been largely restricted to two topics: how to better apply our own violence to the region, and what to do about the refugees. One will deepen the wound, the other is about dealing with the symptoms.

Almost everyone in the Middle East has gone to war, and in the midst of it, Syria has declared war on itself. It’s almost impossible to keep track of who is fighting who, who is allied with who—our NATO ally Turkey is on our side against ISIS, except they’re also bombing the Kurds, who are our main allies in the war against ISIS.

If the focus isn’t on the bleeding, it’s on blaming someone for what’s happening. And everyone blames the Americans, not just for invading Iraq in 2003 and breaking the society, but for not doing enough to intervene in the early days of Syria’s civil war, and a dozen more things as well.

Widening the perspective beyond just the Americans, there are probably a million reasons things have ended up as they have today, and while very few of those events provide any real illumination of the problem, there is one that is almost certainly important. In fact, you could call it the original sin.

When ISIS first launched itself into the global consciousness in June 2014, it did it with an English-language video entitled “The End of Sykes-Picot.” In May 1916, British civil servant Mark Sykes and French diplomat François Georges-Picot concluded negotiations for a secret agreement to divide up the Ottoman Empire once it was defeated—in other words, dismember the caliphate—and split the pieces among First World War allies according to their diplomatic needs and desires, not the ethnic, religious or linguistic reality on the ground.

Whether or not ISIS’s sense of history is technically correct (Iraq and Syria were distinct entities before the agreement), the group believes that the post-First World War fragmentation of the Arab world is a form of lasting oppression, a form of control that prevents the emergence of another caliphate. Sykes-Picot is their symbol of this.

“This blessed advance will not stop until we hit the last nail in the coffin of the Sykes-Picot conspiracy,” vowed ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in his only public speech in July 2014.

What this reveals—besides the compelling way in which one error can create a downward spiral of additional errors and problems until the situation becomes irreversibly broken, disordered and chaotic—is that ISIS is not in itself a new phenomenon, nor is it actually the biggest problem facing Syria.

“Trying to flee murderous

attacks from all sides,

the refugees have decided

that it’s worth almost

anything…to get out.”

ISIS is almost exclusively a Sunni Arab organization and the territory it controls is almost entirely Sunni. Jabhat-al Nusra is also a Sunni organization in Syria, this one allied to al-Qaida. In essence, both are merely Sunni militias. The big problem is the civil war inside Syria—the fact that the majority of the country has turned against Assad, the leader. Yet if Assad were gone, the chaos would likely deepen.

Regardless, the stated mission is clear; the coalition intends to “degrade and destroy ISIS.” But the truth is that airplanes can’t hold territory and bombs don’t destroy ideas. This is especially true when it comes to actually destroying ISIS in the long run, not just containing them territorially in the near term. In the end, restoring the border between Syria and Iraq—the Sykes-Picot border—is perhaps going to be the hardest thing of all.

What became clear during the interviews for this story is that a consensus exists among observers of all types: there are no easy solutions. In fact, there may not be any solutions at all. What follows are the reflections of three high-level thinkers, pondering the strategic problem represented by Syria, Iraq and the ongoing refugee crisis.

The military man: “This will take 20 years and lots of diplomacy.”

Stuart Beare retired from the Canadian Armed Forces as a lieutenant-general, the second highest rank. In his most prominent role, as commander of Canadian Joint Operations Command, Beare was responsible for running Canadian deployments at home and around the world. The strategy to stop the bleeding in Syria, says Beare, begins with some very basic considerations.

“If you step back from the symptoms of the problem,” he says, “and you look at the problem from the perspective of what is really going on, ask yourself ‘why do I care?’ Then you may be able to figure out what problems you’re trying to solve and what outcomes you’re trying to avoid.

“The challenge we have, that I’m seeing in Canada, is that we’re not talking about those things, we’re talking about the symptoms, and the tactical actions we’re doing that can make us feel marginally better about ourselves. Because the discussion we’ve been having isn’t strategic, and it isn’t done on the level of real national interest.”

Beare says there are really just two elements dominating our discussion of the war—fear and humanitarianism. Because of this limited discussion, the range of things we might accept as possible courses of action are also limited.

“Everything is at stake. That is how I’d describe it,” says Beare. “In terms of the instability emerging from the region, it now includes the potential that the region could become a permanently ungoverned space that exports extremism and terrorism. It is in our interest to make sure that doesn’t happen. Regional instability in an area that has energy and is huge for global economic interests, well, that should be in our interest. The connectors here are many. So why do we care? For our own national security interests. We care because of the effect of regional instability on the global economic engine.

“When I hear about European leaders talking about the European Union collapsing, I see that as an existential threat not just to our physical security, but to our social and economic security. And, by the way, you can be human while you’re at it, with regard to the responsibility to protect.

“We care by virtue of our constituencies, because Canada is multi-ethnic and international, so protecting people of all kinds wherever they come from is still in our national interest.

“The other one that’s clear is our relationship with our like-minded partners, our historical partners, and our emerging partners, ones we might not agree with totally, but that we share overlapping interests with—countries such as Egypt, Turkey and Iran. Being engaged is a method for empowering partnerships, and being disengaged makes partnerships difficult.”

The strategic discussion doesn’t end with listing the reasons to care. It also has to envision an end-state, a goal to achieve.

“If I were to describe an end-state,” says Beare, “it would have these qualities: regional stability, good governance, integrity of borders, order through international law, shared opportunity for populations, and not a burden or menace to the rest of the world.”

With that said, Beare is the first to note that achieving that outcome in Syria is somewhat beyond our control.

“This will take 20 years and lots of diplomacy,” he says. “And I don’t mean diplomacy like acquiescence and being weak-willed. Real diplomacy requires clarity. “From my perspective, it’s a long, long game, and we’re not seeing leaders sharing the vision or patience for that long game.”

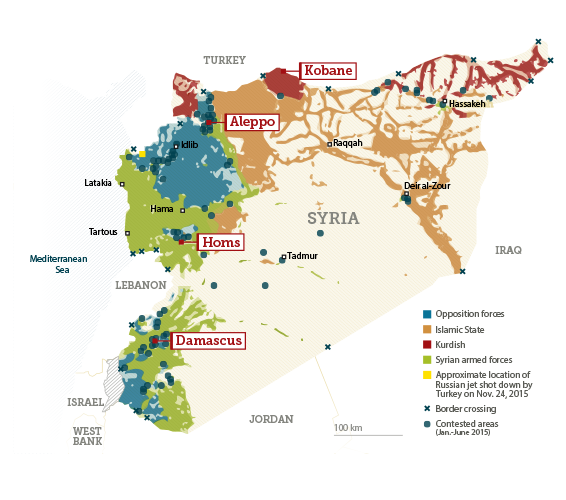

Territorial control

Syrian government, opposition, Islamic State and Kurdish forces each control and contest vast swathes of the country.

The thinker: “Needless to say, we don’t know what to do.”

Michael Ignatieff may be best known in Canada as the former leader of the Liberal Party, the guy who lost to Stephen Harper in 2011. But for a long time before that he was a journalist, writer and academic. He is now a professor at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University. The surge of refugees hitting Europe, he says, is more than any country can safely cope with. “They’ve come in numbers [they] can no longer handle.

“The surge needs to be understood politically—not just as a blind rush for the exits—but as a plebiscite on the war by those whose lives have been ruined by it. After four years in the camps or internally displaced, trying to flee murderous attacks from all sides, the refugees have decided that it’s worth almost anything, including the risk of death by drowning, to get out.

“I fear that the razor wire is going up everywhere, not just on the Hungarian border, and that not even this will stop them coming—not just from Syria but from all the failed and failing states within reach—from Eritrea to Afghanistan.

“The region could

become a permanently

ungoverned space that

exports extremism and

terrorism.”

“Sixty million people are on the move—either as refugees and asylum seekers or internally displaced by civil conflict. We are not in the middle of a spike in migration, but a long surge that will last for some time. Needless to say, we don’t know what to do.

“Canada can and must do more: assisting the front line states—Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan—with funding, taking more refugees, processing them directly in the front line states to save them the desperate journey through the Balkans. And we must think beyond one-time contributions, but as a steady multi-year commitment.”

The strategic analyst: “This will be a long war.”

Thomas Juneau is a former strategic analyst at the Department of National Defence who now teaches political science at the University of Ottawa. He specializes in the Middle East and appears regularly as an expert commentator in the media. Juneau sees no possible way that ISIS can be defeated with military power, no way to end the war in Syria with bombs or troops, no matter how numerous. The only solution that will work is political, and that will take time.

“It’s a good and important idea to think about solutions to all this,” he says, “as long as it’s clear that solutions are going to be extremely difficult to come by and probably not for a few years. But there’s not enough discussion right now of how to solve this. The military aspect to it, in my view, is necessary, but it’s not a solution. There has to be a political solution.

“The world has seen a similar conflict play out. Starting in the 1970s, Lebanon descended into a similar civil war—Sunni versus Shiite versus minority factions—with lots of regional players using the conflict as cover for a proxy war.

“I see the current situation of military stalemate continuing, whether it’s for one or two or five years. If you simplify, there are only two ways a civil war can end: with a military solution—where one side wins, and that’s not going to happen—or a political solution—where there is a negotiated settlement. That is not a prospect at this point in the sense that the actors involved are not interested in negotiating, whether it’s Assad or the Islamic State or the other armed groups. At some point they’re going to be exhausted and enter into negotiations. That’s how this is going to end. And that is not going to happen soon.

“Even from the moment they decide ‘Let’s negotiate,’ it’s going to be a long, protracted and still bloody process. So whether you look at the refugee aspect, whether you look at the humanitarian crisis inside Syria, whether you look at the level of violence inside Syria, whether you look at regional and international interventions, all of these are going to continue because the war is not going to end. Not for a good while, a number of years.

“I don’t know how this is going to end. I have no idea how they’re going to come to a political solution. The first step toward that is exhaustion between the parties. Wait and watch. To some extent, we have limited influence on that. We can apply pressure, but ultimately the main thing that has to happen is exhaustion. That is when they’re going to say okay, we’ve had enough, we need to get out of this. That’s what happened in Lebanon. That war lasted 15 years.”

Tragic stalemate

In the almost endless confusion, there are a number of facts to consider about the situation in Syria: with millions of displaced refugees and with one of its major borders erased, the country is literally emptying out and will probably never exist in the same way again. And while ISIS presents a threat of pretty much apocalyptic insanity, it hasn’t killed nearly as many Syrians as President Assad has. So, in stark utilitarian terms, the president of Syria is far more evil. That said, it might be that Syria is still better off with him than without him.

In the end, the absurd tragedy at the heart of the situation is that we are all now stuck watching this enormous human disaster and it seems we can’t do very much about it.

Advertisement