The sinking of HMCS Ottawa triggered a shift in the navy’s priorities

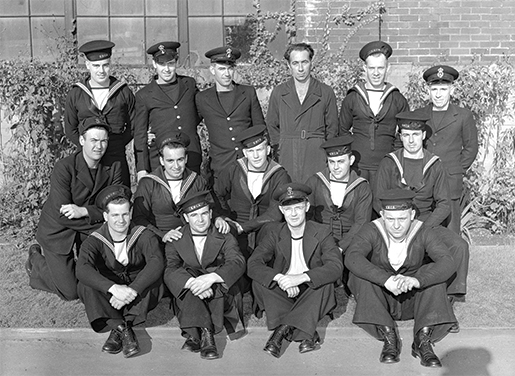

HMCS Ottawa was torpedoed by German submarine U-91 on Sept. 14, 1942. Ten days later, these surviving members of the ship’s company posed in St. John’s. [DND/LAC/PA-204607]

Ottawa was also moving slowly, “slipping along at ten knots,” trying to confirm the radar contacts that Lieutenant-Commander C.A. “Larry” Rutherford hoped were the destroyers HMCS Annapolis and HMS Witch. Visibility was so poor that Ottawa had to close to within 1,000 yards of Witch to confirm who she was.

Meanwhile, on the conning tower of U-91, Kapitänleutnant Heinz Walkerling was watching closely, too. In fact, he had tracked a slow-moving “two funnel destroyer” for some time, and was only 1,000 yards away when U-91 fired two torpedoes.

Pullen, Ottawa’s first lieutenant, was on deck when a torpedo hit the port bow, just forward of ʻAʼ gun. He recalled a rending explosion and a brilliant flash of orange light. “The ship’s forward superstructure, funnels and bridge, all the parts visible from where I stood agape, became momentarily silhouetted by an orange glow.” In the sudden silence that followed, the only sound was that of debris falling into the sea and “clattering onto the upper deck.”

Survivors of a torpedoed merchant ship and HMCS Ottawa return to St. John’s aboard HMCS Arvida on Sept. 15, 1942. [Lt. G.M. Moses/DND/LAC/PA-136285]

When Pullen pushed his way through the door into the forward mess, he walked into “scenes of carnage” and the sight of the sea where Ottawa’s bow used to be. Men were trapped in compartments that he could not open or reach. Two young sailors were entombed in the ASDIC compartment in the bowels of the ship, and their pleas for help could be heard plainly through the voice pipe on the bridge. “What could, what should one do,” Pullen recalled, “other than offer words of encouragement that help was coming when such was manifestly out of the question?”

The good news for the moment was that the bulkhead was holding and Ottawa was only slightly down by her bow. Lieutenant-Commander A. H. “Dobby” Dobson took one look from HMCS St. Croix when she arrived on the scene and sped away to pull merchant sailors from the sea closer to the convoy. Rutherford did not order Ottawa abandoned, and no orders were given to throw her secret books over the side. Sub-Lieutenant Don Wilson took it upon himself to go below and collect the books from the ship’s safe; he was never seen again.

In the meantime, Ottawa’s crew worked to save her. She would have to make the 400 miles to St. John’s in reverse, but HMCS Saguenay had done just that in December 1940, after her bow was shot off 300 miles west of Ireland. So there was reason for hope.

Two young sailors were trapped in the bowels of the ship, and their pleas for help could be heard plainly through the voice pipe on the bridge.

Unfortunately, Walkerling was not done. He saw St. Croix returning to help the stricken destroyer and, according to the RCN official history, circled back to attack her. What he actually fired at, about 15 minutes after the first attack, was Ottawa. This time a lone torpedo hit Ottawa’s starboard side, in the number-two boiler room. The explosion broke the destroyer’s back. She rolled over then quickly split into two. The bow was the first to sink.

“What happened at the end is hard to contemplate for the imprisoned pair [in the ASDIC compartment],” Pullen recalled, “as that pitch-black, watertight, soundproof box rolled first 90 degrees to starboard and then 90 degrees onto its back before sliding into the depths and oblivion. It is an ineradicable memory.”

Fortunately, gunner L.I. Jones had set the depth charges to safe, so none exploded to kill the men who managed to get off when the stern section sank. As the last of Ottawa disappeared, St. Croix sped past on the hunt for a surfaced U-boat spotted by her lookouts. The men in the water shouted “Saint Croix! Saint Croix!” as the old four-stacker raced by, according to Fraser McKee and Robert Darlington, authors of The Canadian Navy Chronicle, 1939-1945. Eventually, St. Croix found and disabled U-411, but it was four hours before anyone returned to help the survivors of Ottawa.

In the meantime, convoy ON-127 steamed quietly and solemnly through the wreckage of the destroyer and its survivors and, as Pullen wrote, “Just as quietly was gone. A tanker in ballast passed so close we could see a cavernous hole in her side.” The damaged ship was probably the F.J. Wolfe, a 12,190-ton tanker torpedoed on Sept. 10 but able to stay with the convoy. The night was very dark, but clear, and the calcium flares on Ottawa’s Kisbee rings (life preservers named for British naval officer Thomas Kisbee) probably illuminated the scene. The men certainly were seen from passing ships. The SS Athelduchess dropped some Carley floats (life rafts designed by American inventor Horace Carley) and the SS Clausina, likely the last ship in one of the columns, stopped to search for survivors—that would have been her duty. However, when she saw HMCS Arvida in the area, Clausina resumed her course, leaving the rescue work to Arvida and HMS Celandine.

Ottawa had sunk far enough to the east to be out of the Labrador Current and just in the Gulf Stream. Even so, the water was cold and the men grew numb and weak as the hours passed. It did not help that the survivors were beset by jellyfish that stung bare flesh and left what McKee and Darlington called “almost unbearable itching later in hospital.” Several men are known to have died when they were struck by one of the rescuing corvettes as it came down off a wave.

In the end, Celandine pulled 49 survivors from the sea, and Arvida recovered 27 more: a total of 76. Not all were from Ottawa; two were from Empire Oil, which Ottawa rescued on Sept. 10. The RCN official history says 137 men perished; McKee and Darlington put the loss at 141. There is general agreement that Rutherford survived the sinking and then drowned after passing his life jacket to a young sailor. Lieutenant George Hendry, Ottawa’s doctor, perished trying to save the life of a man he had just operated on.

The crews of Arvida and Celandine did what they could to ease the suffering. So, too, did the survivors. When Lieutenant L.B. “Yogi” Jensen arrived in Celandine’s wardroom, soaking wet, black with oil, shivering and crawling with jellyfish stings, Ottawa’s Leading Steward Michael Barriault greeted him with a warm, “Good evening, sir, would you like a cup of tea?” Jensen replied with equal civility, “Good evening, Barriault. That would be very nice, thank you!”

The fallout from the battle for ON-127 was rather muted, at least on the western side of the Atlantic. The American admiral at Naval Station Argentia in Newfoundland thought Dobson had conducted an “active” escort, “and took lively countermeasures against attacking U-boats.” He did chastise Dobson for thinking he could establish an ASDIC barrier in front of ON-127 with only five ships, and thought he should have been more aggressive in the use of destroyer sweeps in daylight. The latter was increasingly the preferred American tactic for trying to break up a gathering U-boat pack in the absence of HF/DF fixes on incoming subs. Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray praised Dobson and Escort Group C-4 for a job well done, and blamed the loss of seven ships from the convoy primarily on the lack of modern Type 271 radar.

It took some time for copies of the escort report of proceeds and the convoy commodore’s report to reach the United Kingdom. So senior staff at Western Approaches Command (WAC) did not write their comments on ON-127 until late October, more than a month after the battle.

They were not happy. Commander C.D. Howard-Johnston, the Staff Officer, Anti-Submarine at WAC, was positively cutting. “There is an unnecessary waste of escort’s efforts to sink damaged ‘freighters,’” he wrote. “In one case, Sherbrooke has managed to get 25 miles astern of the convoy in order to sink torpedoed ships. What is St. Croix’s idea?… He is helping to reduce our tonnage by weakening the escort and completing the enemy’s work.”

Captain R.W. Ravenhill, the WAC Operations Officer, shared Howard-Johnston’s concerns and extended them to include the RCN senior staff in St. John’s, which he described as a “complete muddle.” The official WAC report to the Admiralty was a little more discreet, noting laconically “It is the enemy’s purpose to sink our tonnage.”

By the time these words were penned, WAC had every reason to be anxious about further losses, and about the ability of the RCN’s mid-ocean escort groups. To some extent, their criticism of the RCN’s mid-ocean operations in the early fall arose from an admission by the RCN itself that it needed help. The navy simply could not afford to lose Ottawa. HMCS Assiniboine was still under repair following her epic battle with U-210 in August and HMCS St. Laurent was just coming out of a long refit, so the RCN was down to three River-class destroyers. Of the six Town-class destroyers in Canadian service, only St. Croix had the legs for transatlantic work. So at best, the RCN had one destroyer available for each of its four mid-ocean escort forces. Each was supposed to have two.

Two days after Ottawa went down, the RCN asked the Admiralty for help. Ideally, it needed more long-range destroyers, but a couple of the 10 frigates being built in Canada to British accounts would help if the Admiralty would allow the RCN to take them over. The appeal for help after ON-127 marked the start of a brief period when the RCN shifted its priorities from building a fleet that suited its professional ambitions to one that met the immediate needs of the escort fleet, of the war itself. Over the next few weeks, events in the mid-ocean and in the Gulf of St. Lawrence accelerated that shift in priorities.

Advertisement