HMCS St. Francis prepares to take on fuel from a tanker while on escort duty on Nov.7, 1942. [Lieut. Gerald M. Moses/DND/LAC/PA-116335]

By the late summer of 1942, the Canadian navy was stretched thin. But the corvettes were still able to disrupt several U-boat attacks.

Running the North Atlantic war was all about risk management, and things were better in the early fall of 1942. The rampage along the United States coast and in the Caribbean was over. In September, U-517 and U-165 ran amok in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and up the St. Lawrence River, but that was an anomaly. Operating convoys in a river—even one as wide as the St. Lawrence where it opens into the Gulf—left no scope for evasive routing. And with the technology of the day, the Royal Canadian Navy could not find the attackers. Stopping the convoys seemed prudent.

Wolf packs were back in force in the mid-ocean air gap again by September, but in the late summer and early fall there was no cause for alarm. The weaknesses of Canadian mid-ocean escort groups were apparent, at least to Canadian and British operational commands: too few destroyers and poor equipment. But these C groups had killed more than their share of U-boats over the summer. So far, so good.

Early in September 1942, the Germans tried to attack four transatlantic convoys, all of them primarily Canadian escorted.

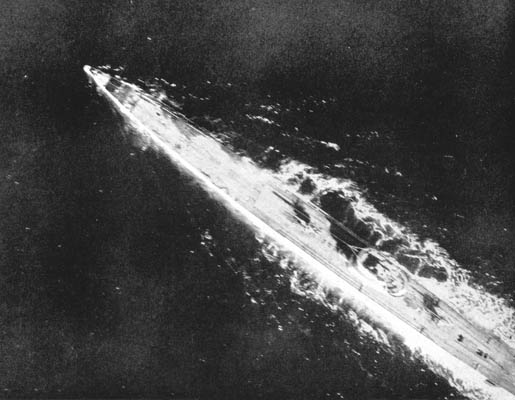

Pursued by aircraft, U-165 begins to dive in September 1942. [DND/PL12814]

Certainly, the Canadians were doing well enough in the late summer of 1942 for the Allies—the British especially—to keep making demands on RCN resources. In August, the Admiralty asked the RCN to provide escorts for the forthcoming landings in North Africa. By stripping the West Coast, the Gulf of St. Lawrence and Western Local Escort Groups, the RCN found 16 corvettes. Among them were most of the RCN’s nine adapted corvettes. These had been ordered in the 1940-41 building program and reflected the adaptation of the original design to oceanic escort work, with higher bows, increased sheer and flare, and improved bridges. Ideally, they ought to have been assigned to the C Groups in the mid-ocean. By August 1942, two were serving alongside the U.S. Navy in the Caribbean, and six of the remaining seven were assigned to Operation Torch, the British-American invasion of French North Africa being planned for November.

The RCN also took care to refit its Torch corvettes for the job. The German air threat from France remained serious, and Italian aircraft still dominated the western basin of the Mediterranean. All of the Torch corvettes received heavier secondary armament—a lot of it. In 1942, Canadian corvettes carried little more than machine guns on the bridge wings and in the after gun tub, which were virtually useless in a surface battle with a U-boat. Torch corvettes received new 20-mm Oerlikon cannon; in some cases—such as HMCS Kitchener—at least four of them. The RCN also had a few recently arrived Type 271 radar sets (intended for the Mid-Ocean Escort Force groups) in Halifax: these too went to the Torch corvettes. Those corvettes unable to fit the new equipment in Canada got it when they arrived in the U.K.

Operation Torch was not the only new commitment the RCN took on in late summer. In September, the western terminus of transatlantic convoys shifted from Halifax to New York, and the RCN assumed responsibility for the additional work. This required breaking the Western Local Escort Force (WLEF) into two sections, north and south of Halifax, because of the limited range of local escorts (short-legged Town-class and British V- and W-class destroyers and RCN Bangor-class minesweepers). WLEF was now fully responsible for nearly 2,000 kilometres of the passage of the main transatlantic convoy route.

These new commitments stretched the RCN to its final limits. Certainly, Rear Admiral Leonard Murray, Flag Officer in Newfoundland, noticed. On Sept. 18, just before he left St. John’s to become Commanding Officer, Atlantic Coast in Halifax, Murray complained to Ottawa that he was unable to keep refit schedules for mid-ocean escorts because his C groups were chronically under strength. The officers and men of Murray’s C groups were increasingly unhappy about their plight, too. They coveted the latest RCN corvettes—the ones built for oceanic escort—and those equipped with powerful secondary armament and the latest radar as they augmented mid-ocean groups en route to the United Kingdom.

So the RCN was stretched exceptionally thin by the late summer of 1942, and by September, portends of future trouble in the mid-Atlantic were evident, as the wolf packs started to focus on Canadian-escorted convoys. After the battle for ON-127 early in September, the Germans tried to attack four transatlantic convoys, all of them primarily Canadian escorted. SC-99 was intercepted on Sept. 13 and briefly pursued by five U-boats. The escort of that convoy, C-1, had only one destroyer, the four-stacker HMCS St. Francis, but seven RCN corvettes—none of them had modern radar. So it was fortuitous that the U-boats probing for SC-99 were distracted by ON-129, which was caught trying to skip around the edge of their line. ON-129 was escorted by C-2, which was built around two old Royal Navy destroyers, HMS Burnham and HMS Winchelsea, and a gaggle of RCN corvettes. C-2 disrupted successive attempts by some U-boats to assemble for an attack, while the other U-boats scrambled to intercept convoys headed in opposite directions. The result of all this was that both SC-99 and ON-129 escaped without loss. So too did HX-206, escorted by a British group.

The Germans reformed their wolf packs and, late in the month, snagged SC-100, a convoy of only 24 ships escorted by A-3. The group was notionally American and led by U.S. Coast Guard Cutters Campbell and Spencer. But the bulk of A-3 was RCN corvettes. Trillium, Mayflower and Bittersweet, although HMC ships, were still British property and had been modernized with extended foc’sles, improved sonars and modern Type 271 radar in the U.S. in early 1942. The other RCN corvette in A-3 was HMCS Rosthern, still poorly equipped and not yet modernized. A-3 was joined for SC-100 by the Torch corvettes HMCS Lunenburg, HMCS Weyburn and HMS Nasturtium.

So A-3 was a large and very capable group. The senior officer, Capt. Paul Heinneman, USCG, kept a tight screen and, in the absence of high-frequency direction-finders (HF/DF), sent out distant sweeps to disrupt the pack of 20 U-boats swarming around SC-100. These efforts were largely successful. One ship was lost to a surprise daylight submerged attack, and another when it straggled during the gale which struck the convoy late in its passage. The Germans also got distracted again, this time by convoy RB-1, a one-off convoy of Hudson River steamers headed to Britain, which the Germans mistook for a troop convoy.

The gale and the scramble to redirect U-boats to RB-1 also prevented the subs from getting a firm grip on ON-131 at the end of the month. The convoy’s escort, C-3, was busy nonetheless. The senior officer, Commander D.C. Wallace, RCN in HMCS Saguenay, used HF/DF fixes from the convoy commodore’s ship to push U-boats away as they made contact. Only one of the 15 U-boats chasing ON-131 got near enough to fire torpedoes, and they detonated prematurely.

By the time the Germans called off operations against ON-131 on Sept. 30, they had little to show for a month of effort. Roughly 17 transatlantic convoys passed through the air gap that month. The Germans made solid contact with five convoys in the mid-ocean that month, all of them Canadian escorted. It is not clear if the RCN was aware of the alarming frequency with which their convoys were being intercepted. The British later ascribed this high interception rate to careless Canadian use of radios, which could be detected by shore stations.

More recently, Canadian historians have discovered that the Germans were homing in on Canadian 1.5-metre radar. In August 1942, U-boats began fitting a radar-warning device to help them avoid air attack while crossing the Bay of Biscay. A simple antenna lashed to a wooden cross, the Metox—named after its French inventor Metox Grandin and also known as the Biscay Cross—could detect the ground wave of the RCN’s Type SW1/2C search radars. So the lack of Type 271 radar in C groups was a double source of weakness.

HMCS Bittersweet is towed by HMCS Skeena in May 1943. [LAC/PA-164043]

In early October, the Germans were still struggling to locate and attack convoys in the mid-ocean. HX-209 (B-4) was found close to the eastern edge of the air gap in the first week. The U-boats were rash enough to push their efforts into air cover and lost two subs to British aircraft. The next week ON-138 (B-2) passed right through the middle of a pack named Puma, and eight U-boats were assigned to attack. None got through. It was believed at the time that radar and good use of HF/DF fixes saved ON-138 from attack, but we know now that the pack was distracted by contact with ON-139 coming up from behind. That convoy, escorted by C-2, lost two ships in a surprise attack. The U-boats then fumbled efforts to concentrate on either convoy and both escaped.

Meanwhile, the Germans finally got their teeth firmly into the eastbound convoy SC-104. U-221 sighted the convoy on Oct. 12 just east of Newfoundland, and a battle developed over the next four days. The escort B-6 (British destroyers HMS Fame and HMS Viscount and four Norwegian corvettes) was very well equipped; all had Type 271 radar and the destroyers had HF/DF sets. Poor weather in the opening phase of the battle allowed U-221 to penetrate the convoy and sink three ships during the first night. On Oct. 13, attempts by the escort to drive off the assembling pack with HF/DF directed sweeps were unsuccessful and that night four U-boats attacked: U-221 sank two ships, and three other U-boats each sank one. On Oct. 14, in improving weather, HF/DF directed sweeps drove off most of the shadowers, and that night all attempts to penetrate the convoy were stopped by radar. That night and the next day, Fame and Viscount each rammed and sank a U-boat: the Norwegians damaged another.

The battle for SC-104 ended as something of a draw; eight ships in exchange for two U-boats. The British were pleased, and B-6’s defence of SC-104 became the standard against which the RCN would be judged. As the navy was about to discover, it helped if the escort group had the latest equipment and a couple of destroyers. Otherwise, the results could be disastrous.

Advertisement