In the summer of 1942, Canada’s escort fleet excelled at protecting supply convoys from German subs

While the corvette HMCS Oakville battled the German submarine U-94 astern of convoy TAW-15 in the Mona Passage between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico on Aug. 28, 1942, another German sub, U-511 commanded by Kapitanleutnant Friedrich Steinhoff, arrived on the scene.

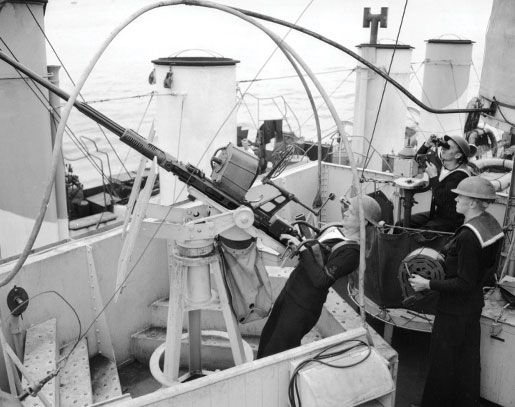

A sailor aboard HMCS Skeena scans for German U-boats in May 1943. [Gerald Thomas Richardson/DND/LAC/PA-166889]

Lawrence saw the attack from the conning tower of U-94. “Two ‘whumps’ of torpedoes striking home told me other U-boats were attacking,” Lawrence wrote in his memoir. “A pillar of flame erupted, mounted and briefly took the shape of a crooked tree.…” Escorts firing starshells and other illumination flares added to the pyrotechnic display.

Steinhoff’s first victim was the 13,031-ton British tanker San Fabian, laden with 18,000 tons of fuel oil for the United Kingdom. Only her master, one gunner and 31 crew, from a total crew of 59, were picked up by USS Lea. The second ship struck was the 8,968-ton Dutch tanker Rotterdam, filled with 12,000 tons of gasoline. She settled quickly by the stern, taking 10 of her crew of 51 with her; survivors were rescued by USS SC-552. The last ship struck, the 8,773-ton American tanker Esso Aruba carrying 104,000 barrels of diesel fuel, was severely damaged. She was later beached and salvaged in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

None of the escort made contact with U-511, and Steinhoff did not linger. The U-boat was damaged from her own hasty crash dive and retired to make repairs. Steinhoff had reason to be pleased. Tankers were prime targets and he had hit three. It was enough. TAW-15 arrived at Key West, Florida, without further incident on Aug. 31. After Oakville’s Lieutenant-Commander Clarence King ordered a brief stop in Guantanamo Bay for repairs, the corvette eventually made it back to Halifax on her own steam.

Angus L. Macdonald (centre), the federal minister of defence for naval services, inspects anti-aircraft guns aboard HMCS Restigouche, accompanied by Commander H.N. Lay (left) and Rear-Admiral P.W. Nelles in September 1940. [DND/LAC/PA-104272]

So when Oakville arrived in Halifax, “public relations types swarmed aboard with a battery of photographers.” When Lawrence declined to go on a public-relations tour, he “was sent for”—by whom, he does not say. Angus L. Macdonald, the federal minister of defence for naval services, had told the press that Oakville’s victory was “a striking example of the close relationship in which the navies of the United States of America and Canada are working in the Allied cause.” Lawrence was told bluntly to “go and bloody well talk about that striking example.”

So off he went, first to Toronto, then Oakville, Port Arthur (where Oakville was built) and, finally, New York City. He spoke at lunches, shook hands, had his photo taken with women’s groups who knitted for the navy, spoke to the men who had built his ship, and endured endless interviews by the media. In New York, he met Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia, gave interviews to major newspapers and radio shows, and was a featured guest on Miles Bolton’s syndicated live radio show “We the People,” which reached three million Americans. Bolton generously gave Lawrence nearly a half hour to tell his tale. But Lawrence was so long-winded that he only got to the point of initial contact with U-94 when the producer signalled two minutes remaining. Lawrence blasted through the high drama of the boarding in those two minutes. The show then went to commercial before simply going off the air, and the cast and crew quickly dispersed. So much for Lawrence’s fame.

King earned a Distinguished Service Order for the sinking of U-94, the typical award to the captain of a ship that sank a U-boat. Lawrence received a Distin-guished Service Cross, and Stoker A.L. Powell and Stoker David Wilson (who oversaw damage control in the boiler room) each received a Distinguished Service Medal.

Lawrence and Powell’s exploits were later immortalized on a dramatic war poster showing the two clambering across the U-boat’s deck, pistols in hand—with Lawrence’s shorts restored by the artist for the benefit of the general public. What the navy got out of all this remains unknown. If the existing literature is any indication, especially the work by Michael Hadley tracking the impact of U-boat depredations in Canadian waters, and Richard Mayne’s revelations about the MacLean affair, the tale of Oakville and U-94 had little impact on the mood of the home front.

The navy might have fared better had it trumpeted the fleet’s overall success at sinking U-boats in the summer of 1942. In July and August, nine U-boats were sunk by Allied warships in the North Atlantic from Gibraltar to the Caribbean and north. Four of those were destroyed by Canadian escorts: U-90 on July 24 by St. Croix; U-558 on July 31 by Skeena and Wetaskiwin; U-210 on Aug. 6 by Assiniboine; and U-94 on Aug. 28 by Oakville. This was an impressive record at a time when not much seemed to be going well for the RCN. And what the navy did not know at the time was that another U-boat, U-756, was sunk by a Canadian corvette in the mid-Atlantic in the early hours of Sept. 1.

HMCS Morden, seen from the deck of HMCS Kamloops. A postwar reassessment credits the Morden with the sinking of U-756 in the North Atlantic Ocean. [flickr.com/photos/16118167@N04/6755827577]

In the path of SC-97 lay no less than three U-boat packs. “Vorwarts,” composed of nine U-boats, was southwest of Iceland; “Stier,” with six U-boats, was farther south: both were trolling for convoys. The nine subs of group “Lohs” were moving to a refuelling rendezvous southeast of Newfoundland. Vorwarts had narrowly missed a fast convoy on the night of Aug. 30–31 when, in the words of the RCN official history, “SC-97 stumbled into Vorwarts the next morning.”

The first U-boat to make contact, U-609, submerged ahead of SC-97, then penetrated the escort screen before attacking from periscope depth in daylight the next morning. Two ships, the SS Bronxville and the SS Capira, were struck and both went down. Morden and the rescue ship HMS Perth picked up survivors while the rest of the escort attacked underwater contacts. U-609 slipped away unscathed. For the next 48 hours, C-2, now aided by the destroyer USS Schenk, held Vorwarts at bay. On Sept. 1, aircraft from Iceland arrived to help. Subsequent attempts to press home attacks and maintain contact were thwarted by naval and air escorts, and several U-boats were damaged. The Germans gave up the chase on Sept. 2. At the time, all the Allies knew was that SC-97 had punched its way through a large U-boat concentration with minimal losses.

Crew aboard HMCS Morden demonstrate the ship’s 20-mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft gun during training off Halifax on Aug. 3, 1943, shortly before sailing to Plymouth, England. [Edward W. Dinsmore/DND/LAC/PA-139895]

In the case of SC-97, the only kill subsequently awarded was to a U.S. Catalina amphibious aircraft of Patrol Squadron 73 on Sept. 1. Its attack on that day seemed to coincide with the disappearance of U-756, which German authorities recorded as missing on Sept. 3 and which the Allies also tracked as missing. In the 1980s, a thorough reassessment of the evidence, especially U-boat logs, revealed that the American Catalina had attacked U-91. Through a process of elimination, the only attack that could account for the loss of U-756 was that by Morden.

The commanding officer of Morden, Lieutenant J.J. Hodgkinson, RCNR, reported an attack on a U-boat shortly after midnight on Sept. 1, and felt at the time that his ship had done well. Morden was screening SC-97 when her radar picked up a contact, followed shortly by a U-boat sighting. The sub got under before Hodgkinson could ram, but three depth-charge attacks followed swiftly: two charges were dropped as Morden ran over the swirl of U-756’s dive, five more were dropped in a deliberate attack, and then a 10-depth-charge pattern was dropped on a solid sonar contact. Hodgkinson reported that “it was difficult to imagine that the U-boat could have avoided being hit by the depth charges.” No wreckage or bodies were recovered, but 55 years after the incident, Morden was credited with the kill.

The destruction of U-756 capped a highly successful five-week run of U-boat kills by the RCN: five in all. Unfortunately for the RCN, no one noticed—or cared—at the time. And as the summer of 1942 waned and the mid-ocean began to fill up with German subs, the RCN’s public drubbing by U-boats in home waters and by MacLean in the press was about to be mirrored on the North Atlantic run.

Advertisement