Artist Arthur Hider depicts Canadian soldiers in action at the Battle of Paardeberg in February 1900. [CWM/19920019-065]

The newspapers called it “Black Week.”

Between Dec. 10 and 17, 1899, three columns of British regulars led by experienced generals were defeated at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso during the opening battles of the Boer War. Citizen soldiers of the tiny Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State caused nearly 3,000 casualties as the Brits attempted to relieve the besieged towns of Mafeking, Kimberley and Ladysmith.

The public at home was shocked, while other European powers began to question the dominance of the British Empire. But that coalition had already answered the call and contingents from Australia, India, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada stepped in to help.

The conflict, also known as the South African War, had begun just two months earlier. In the wee hours of Oct. 11, 1899, Boer troops advanced south and east into the British territories of Cape Colony and Natal at the southern tip of Africa.

Canadians were sharply divided over sending troops to assist Britain. Generally, English Canadians were supportive, while French Canadians, seeing parallels between themselves and the Boers, were not. Wilfrid Laurier, the country’s first French-Canadian prime minister, opposed sending his brethren to fight in a war in which he felt no Canadian interests were at stake. But Laurier misjudged the overall mood of the country.

After early setbacks, British Field Marshal Frederick Roberts took command of the Imperial forces, while Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter led the Canadian contingent.[National Library of Ireland on The Commons/Wikimedia]

Throughout the summer and fall before the war, partisan newspapers whipped the public into a frenzy of Boer bashing. Laurier finally acquiesced to public opinion, or at least that of English Canada. In mid-October, he offered to send 1,000 volunteers to South Africa. The British promptly accepted.

Recruiting started immediately. The 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry (RCR) was made up of volunteers—150 from the 1,000-man Permanent Force and the remainder from 82 militia units. Eight 120-man companies were assembled in Victoria, Vancouver and Winnipeg for ‛A’ Company; London for ‛B’; Toronto for ‘C’; Ottawa and Kingston for ‛D’; Montreal for ‛E’; Quebec for ‛F’; Saint John, N.B., and Charlottetown for ‛G’ and Halifax for ‛H.’

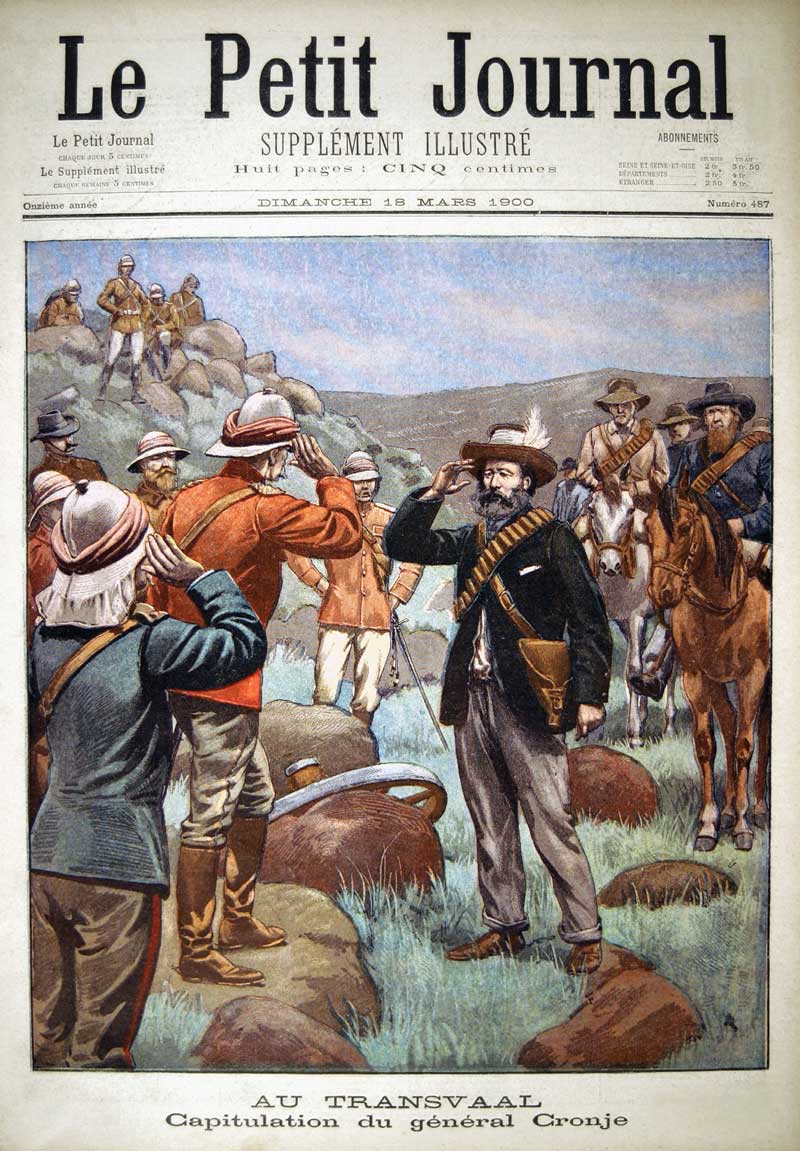

Roberts’ praise acknowledged the Canadians as being “instrumental in the capture of General Cronjé and his forces.” The Boers reportedly dubbed them “fire eaters.”

Amazingly, authorities recruited, examined, organized, clothed, equipped, assembled and dispatched overseas the 1,039-man battalion in October in just 16 days. The government selected Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter, Canada’s most experienced soldier, to command the country’s first-ever overseas expeditionary force.

When the RCR arrived in Cape Town at the end of November, the Boers surprisingly held the upper hand and had British forces bottled up in Mafeking, Kimberley and Ladysmith. The day after the Canadians arrived, they moved north by train.

After pausing for a few days at various stops en route, the RCR reached Belmont on Dec. 9, just before Black Week began. At Belmont, the Canadians trained and performed outpost duties.

The defeats of Black Week were followed by the embarrassment of Spion Kop on Jan. 24, 1900. There, some 20,000 British soldiers were decimated by 8,000 Boers and forced to retreat.

The RCR moved to Graspan and joined 19th Brigade, part of a 35,000-man British force commanded by Field Marshal Frederick Roberts, the newly appointed commander in South Africa. The diminutive, one-eyed, 67-year-old Roberts, affectionally known as “Bobs” to his soldiers and the public alike, was one of Britain’s most capable officers. He had been sent to turn the tide.

In mid-February, the RCR began a gruelling, five-day cross-country trek across the veldt under Roberts. It was marked by thirst, hunger, heat and exhaustion. Roberts’ goal was the Orange Free State capital, Bloemfontein. But a Boer force of 5,000 men under General Pieter (Piet) Cronjé stood in the way.

The two sides met at Drift, a ford at the Modder River. While Cronjé dug defensive positions into the river’s north bank, he sent his wagons and the families about three kilometres further upriver to form a protective barrier called a laager.

The Canadians’ initial experiences in battle on Feb. 18 weren’t good. The desperate fighting that marked Canada’s first overseas exchange of gunfire ended in failure, with 21 killed and 60 wounded. “Bloody Sunday,” as the soldiers called it, was Canada’s costliest engagement since the War of 1812.

After another abortive attack on Feb. 20, the RCR performed various outpost duties over the next few days, designed to keep the Boers from escaping. As the British gradually tightened a noose around the Boers and shelled their positions continuously during daylight, Cronjé moved closer to the laager and dug in positions along both sides of the riverbank. Inside the circled wagons, which stretched in a three-kilometre arc along the north side of the Modder, conditions were deplorable.

The Canadians were in rough shape, too. Sickness, wounds and death had reduced the original 1,039-man battalion to 708. Those who remained were a bedraggled looking lot. Unable to wash or shave most of the time, they had been wearing the same lice-infested clothes for two weeks. Extremes of heat and cold, as well as insufficient rations, only added to their misery.

To make matters worse, hundreds of dead Boer animals floated downstream, their decomposing bodies polluting the water and filling the air with a sickening stench. When the Canadians got the odd rest day, they washed their bodies and clothes with river water and used it for drinking and cooking. Illness struck.

On Feb. 26, the RCR relieved a British battalion in the front-line trenches opposite the west end of the Boers, only 550 metres from the dug-in farmers. The next day held special significance for both sides.

Feb. 27 nineteen years earlier, the Boers had triumphed over the British at the Battle of Majuba Hill. Their victory secured the former’s independence and humiliated the latter. The British army was anxious to avenge that defeat.

The responsibility for the attack fell to 19th Brigade, now reinforced by additional infantry units and a company of Royal Engineers. Because the RCR held the front-line trenches, they would lead the assault, assisted by the Brits. The green Canadians were about to undertake one of the most difficult operations in warfare: a night attack.

An artist depicts the British defensive line during the Battle of Majuba Hill in February 1881. [Fidodog14/Wikimedia]

At daybreak, from the safety of their hastily dug new trenches, the tenacious Maritimers realized that they overlooked the enemy.

By 10 p.m., the forward RCR companies, ‛C’ through ‛H,’ were in position for the assault. Their trenches stretched northward for more than 300 metres from the riverbank. ‛A’ Company was sent south of the river, while ‛B’ Company was in reserve.

Shortly after 2 a.m. on Feb. 27, 500 Canadians climbed out of their trenches as quietly as possible and formed two lines six paces apart. The front line had bayonets fixed. To keep direction in the darkness, the soldiers advanced shoulder-to-shoulder, “clasping the hands of those on our left and being clasped by the waist of those on our right,” according to a participant.

Around 2:45, when the Canadians were less than 100 metres from the enemy trenches, a soldier bumped into a tin can filled with rocks hanging from a wire. The primitive warning system alerted Boer sentries, who began firing.

This was quickly followed by withering fire from the Boer lines as the farmers scrambled out of their dugouts. Fortunately, the sentries’ shots gave the Canadians enough time to throw themselves to the ground and avoid the worst of the barrage. British engineers started to dig in while the Canadians returned fire.

Although the casualties from the first shots were surprisingly light, ‛F’ and ‛G’ companies, who were closest to the Boer lines, in some cases only 60 metres away, suffered the most. They sustained six killed and 21 wounded in the opening volley.

For the next 15 minutes, the two sides traded shots. The RCR front line kept up a steady fire, while the second line and the engineers dug in. Occasionally, a frustrated soldier in the second line dropped his shovel and crawled to the front rank to return a few shots in the enemy’s direction.

A few, paralyzed by fear, hugged the ground and didn’t fire at all.

Suddenly, an authoritative voice from the left flank called out, “Retire and bring back your wounded!” Most of the soldiers were only too happy to oblige. The Canadian fire lessened, men stood up and ran to the rear. As they fled, fire from the Boers felled several of them.

Soldiers of ‛C,’ ‛D,’ ‛E’ and ‛F’ companies were soon crammed into their original trenches, which were now occupied by a British battalion. They remained there for the rest of the battle. But the two companies from the Maritimes, ‛G’ under regular army Lieutenant Archibald (Archie) Macdonell and ‛H’ under Halifax militia Captain Duncan Stairs, either didn’t hear the order or purposely chose to ignore it. They stood their ground, along with a few Royal Engineers.

At daybreak, from the safety of their hastily dug new trenches, the tenacious Maritimers realized that they now overlooked the enemy. They could fire into the Boer dugouts along the riverbank, as well as into their laager.

When darkness began to fade around 4 a.m., several Boers emerged from their trenches to survey the battlefield. The Maritimers immediately opened up with well-disciplined fire that drove the enemy back into their holes. The Boers returned fire for about an hour or so, when suddenly those in the forward enemy trenches shouted out that they wanted to surrender.

Initially, the Canadians continued to fire on the Boers. They had heard stories about Boers pretending to give up, only to open fire again. Around 6 a.m., a lone Boer climbed out of his trench carrying a white flag and walked toward the Canadians. All action ceased. Other Boers quickly followed, surrendering to ‛G’ and ‛H’ companies.

Troops of the Royal Canadian Regiment cross the Paardeberg Drift in February 1900. [Reinhold Thiele/LAC/C-014923]

The leading British and Canadian troops advanced warily, bayonets fixed, past the Boer trenches and into the laager. Roberts arrived to accept Cronjé’s surrender. Most Boers never forgave him for capitulating, especially on the anniversary of their great victory at Majuba. Cronjé’s untimely and unexpected capitulation, with nearly 10 per cent of the entire Boer army, opened the way for the eventual Imperial victory.

Late that afternoon, as the RCR searched the laager for souvenirs and food, an honour the British gave them in recognition of their role in the victory, Roberts rode over to congratulate the Canadians. He praised them and acknowledged them as being “instrumental in the capture of General Cronjé and his forces.” “Canadian,” he went on to state, “now stands for bravery, dash and courage.” The Boers reportedly dubbed the Canadians the “fire eaters.”

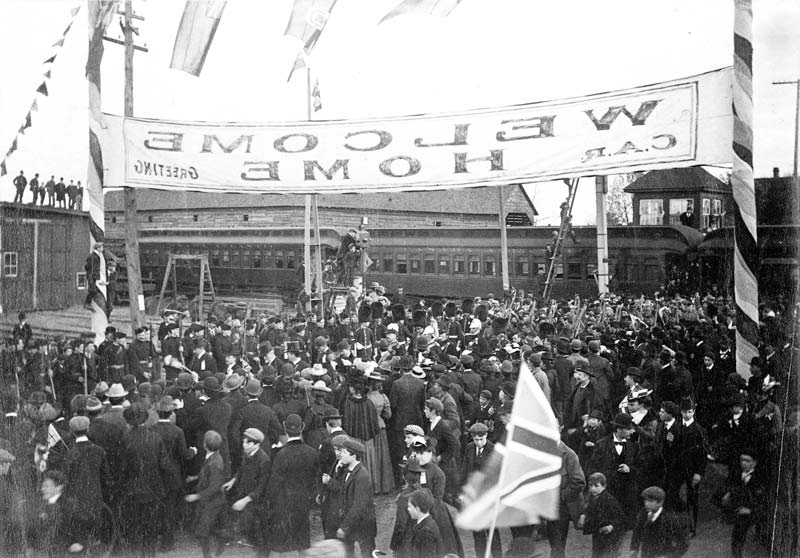

Once Roberts’ dispatches reached Britain, Canada and the rest of the Empire heaped praise on the soldiers of the RCR. Canadians had just won their first foreign battle and the first significant Imperial victory of the war at a cost of 13 dead and 36 wounded. For his courageous actions during the battle, Private Richard Thompson was awarded a Queen Victoria’s Scarf of Honour (see “Artifacts,” September/October 2024).

The battle quickly became known as “The Dawn of Majuba Day,” avenging the earlier defeat. Many hailed it as a turning point in the conflict and the beginning of the reversal of British fortunes.

And Canadian soldiers played a full part in that victory.

Paris’ Le Petit Journal newspaper depicts the surrender of Boer General Pieter (Piet) Cronjé.[ INERFOTO/Alamy/APE89K]

Post Paardeberg

With Cronjé defeated, the RCR participated in the general Imperial advance on the Orange Free State and Transvaal capitals. By now, the Boers had decided that set-piece battles were not to their advantage and resorted to hit-and-run tactics conducted by roving bands of commandos.

On March 15, after a grueling march averaging 25 kilometres a day, the Canadians entered Bloemfontein unopposed. Battles at Israel’s Poort, Thaba Nchu, Zand River and Doornkop Hill followed, opening the way to Pretoria. On June 5, the RCR, now reduced to 437 men, marched into the undefended Boer capital.

Lines of communications duties followed at various railroad stations until the regiment’s time was up. After almost a year in South Africa, the RCR returned to Canada and was disbanded.

Advertisement