HMCS Kamsack in the 1940s. [Bill Gard/RCN History.org]

The soothing waves of Prairie wheat rippling across the flatlands that bridge the country east to west bore little of the anger, isolation or dangers that Poseidon brought down on the lumbering convoys of the Second World War.

The miseries wrought by the sea don’t begin to address the lingering death that lurked beneath the waves, ever-present in the form of German Admiral Karl Dönitz’s wolf packs.

“What a miserable, rotten hopeless life,” Leading Seaman Frank Curry of Winnipeg wrote in mid-Atlantic on Aug. 30, 1941. A Saturday—but who knew?

“I cannot imagine a more miserable existence than this of being caught on a corvette in the Atlantic. An Atlantic so rough that it seems impossible that we can continue to take this unending pounding and still remain in one piece. One’s joints ache and ache from the continuous battle of trying to remain upright.”

Granted, the fresh air, big skies, gaping seascapes and bitter cold were not totally unfamiliar to the farmers, grain elevator operators, railway workers and others who, alongside lumbermen from B.C., fishermen from Nova Scotia, and a cross-section of other Canadians, surely had little idea what they were signing up for when they joined the navy.

A convoy of ships awaits departure in Halifax’s Bedford Basin in 1942. [LAC/PA-112993.]

Canada’s once-proud merchant fleet had shrunk to 37 ships and roughly 1,500 seafarers. Another 25 Canadian-owned vessels were under foreign registry.

Just three shipyards employed fewer than 4,000 people.

Between 1939 and 1945, however, the industry expanded to 90 yards on both coasts, the Great Lakes, even inland. They employed more than 126,000 workers.

They built some 4,047 naval vessels, including 487 warships, 400 cargo vessels and more than 3,000 landing craft. At its wartime peak in September 1943, United Shipyards in Montreal delivered the 10,000-tonne SS Fort Romaine, a cargo ship, in a stunning 58 days. The vessel arrived in Britain with a full cargo 28 days after its launch.

By war’s end, Canada had the world’s third-largest navy, consisting of more than 400 ships and 90,000 sailors. For better or worse, at its heart were the corvettes—glorified fishing trawlers more suited to near-shore waters than high-seas maneuvers.

They were small, about 62.5 metres long with a displacement of 950 tonnes. The early Flower-class corvettes carried five officers and a crew of some 70 men, sometimes more.

“The Spring Board” by John M. Horton depicts the flurry of dockyard activity in Halifax during the Second World War. [John Horton/Government of Canada]

“They were admirably seaworthy and able to withstand the worst North Atlantic storms,” wrote Lieutenant (N) William Pugsley in the book Saints, Devils and Ordinary Seamen. “That did not make the corvette a comfortable ship: as soon as the sea gets choppy, corvettes tend to roll and pitch wildly.

“The fo’c’sle is too short to prevent sheets of water from crashing down on the deck, and the men cannot leave their mess without getting drenched. When the weather is bad, water is everywhere.”

They spent long, monotonous months plodding back and forth across what Pugsley described as “the trackless waste of grey seas that were never at rest,” their weary crews on relentless rotations of day and night watches, sleeping in common areas, living on bland food and brackish water, playing cards and writing letters home.

It was a damp, dismal existence. Seasickness was rampant on early voyages. In the middle of the vast ocean, there was no social distancing aboard a little corvette. A hundred men could be crammed into a space built for 50.

“How much longer—this continuous battle of weariness, dirty and sour smelling mess decks that are more like pigpens than a place to live,” Curry wrote on Monday, July 27, 1942. “The poor cooks have an impossible task in trying to get a hot meal for the crew, what with pots wedged on galley stoves and meals piling up in a corner of the galley with our little ship at the mercy of the Atlantic.

“I feel that they have about the most miserable job in the whole mouldy outfit. If ever the label hero could be tacked on anyone, surely our cooks aboard a corvette in rough seas deserve it.”

A painting by John M. Horton depicts HMCS Sackville on North Atlantic convoy duty. [JOHN M. HORTON, BEAVERBROOK COLLECTION OF WAR ART/CWM—19840654-001]

“Ship is taking quite a beating in the rough going, and everyone is quiet and tense, with very little in the way of conversation going on,” Curry wrote on Sunday, July 12, 1942. “The crew can see very little to talk about when the going is grim. Just short, curt replies to short, curt questions.

“Even the ship’s clown takes on the mood of the ship. I do not imagine we are a very lively group to live with under such circumstances.”

Curry was a sonar operator aboard HMCS Kamsack, a Flower-class corvette named for a town in Saskatchewan that, to this day, has a population of just about 1,800. The vessel was launched by Port Arthur (Ont.) Shipbuilding in May 1941.

“I thought it had been rough before,” Curry wrote seven months after Kamsack’s launch, almost to the day. “Now I know something of the meaning of rough seas.

“Mountainous seas are breaking completely over the ship, and it is turning into massive coatings of ice as it hits. We are sheathed in sixteen inches of ice and I do not know what keeps us from going to the bottom of the Atlantic as we pitch, toss, roll and do everything else imaginable. Sure hope the rivets hold under all this pounding.”

The mess deck, he said in another entry, is “a terrifying place to venture near, knee-deep in sea water, tables smashed, clothes floating around in it, breakfast stirred in, the crew in an almost stupor from the nightmarishness of it all.

“If only they could portray all this in their recruiting posters.”

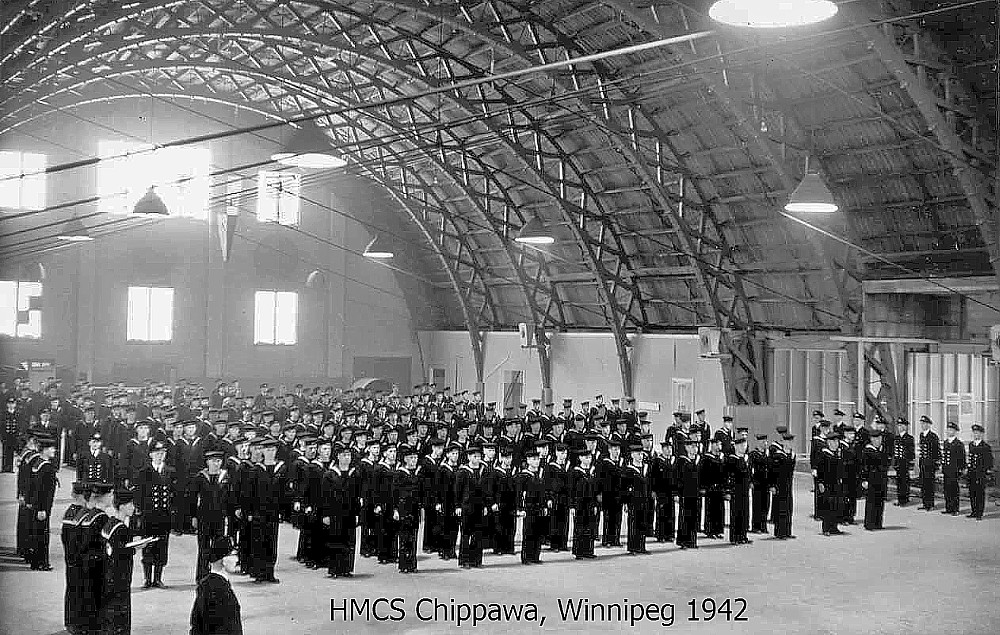

A 1942 photo of HMCS Chippawa’s assembled company after the RCN commandeered the Winnipeg Winter Palace. [Iain MacNeill]

Overall, Chippawa was the third-most prolific wartime supplier of RCN personnel, after the main ports of Halifax and Esquimalt, B.C. Its members still boast that Prairie boys made the best sailors.

They were charged with protecting the Allied lifeline—Britain and the Soviet Union’s lifeline—as they escorted all manner of merchant ships carrying critical food, lumber, iron, steel, oil, equipment and fighting men across treacherous waters.

Flower-class corvettes comprised half of all Allied convoy escort vessels in the North Atlantic during the war. They were among the most beloved and disrespected ships of their time, inspiring a spectrum of emotions in those who sailed them.

They were the last navy ships to be crewed, primarily by volunteer citizen sailors. The brightest and the best, along with the career sailors, tended to go to the larger ships, such as destroyers and frigates.

Two years into the war, corvette Commander Jim Prentice warned Ottawa that “the majority of the RCN corvettes have been given so little chance of becoming efficient that they are almost more of a liability than an asset to an escort group.

“The commanding officers have apparently been given no instruction in convoy work and little chance to train their officers, most of who are without sea experience of any sorts,” he said. “It is as though we were attempting to play against a professional hockey team with a collection of individuals who had not even learned to skate.”

In 1941, the Allies were losing supply ships to U-boats faster than they could be built. At the height of the U-boat war, in 1942-43, as many as 100 supply ships were sunk each month. More than 70,000 Allied seamen, merchant mariners and airmen died over the course of the 2,074-day battle, including 4,600 Canadians.

“The only thing that ever really frightened me was the U-boat peril,” Britain’s wartime prime minister, Winston Churchill, wrote in his 1949 memoire. “How much would the U-boat warfare reduce our imports and shipping? Would it ever reach the point where our life would be destroyed?

“Here was the slow, cold drawing of lines on charts, which showed potential strangulation.”

The Battle of the Atlantic has been described as history’s longest, largest and most complex sea battle, pitting the navies of Canada, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, France and others against Nazi Germany’s Kriegsmarine and its lethal U-boat fleet. With nothing short of the future of the free world at stake, it demanded a Herculean effort, technological innovation and untold resources.

By the time it was over, some 3,500 merchant ships and 175 warships had been sunk; 783 of 1,155 U-boats were on the bottom, having taken with them 28,744 of just over 35,000 unterseeboot crew—a death rate exceeding 82 per cent, the highest of any service in any conflict in the history of modern warfare.

The U-boats lay in wait as the convoys, moving only as fast as the slowest ship, crossed into The Black Pit, out of range of air support. For all the monotony aboard ship, the periods before, during and after action were filled with suspense.

“Terrific explosion just at dark and a 10,000-ton merchantman went to the bottom in less than a minute,” Curry wrote in the spring of 1942. “This was followed in rapid succession by two more terrible explosions within minutes and two more large ships, torn in two, plunged out of sight. A terrible feeling to see the flickering lights of survivors in the water go out one by one…. We moved on into the night.”

Curry’s diary entry for Saturday, May 16, 1942, read: “We spent a terrible night—one that will never be forgotten by me.

“As we hurled ourselves onward into the teeth of mountainous seas at full speed, we made an all-out effort to reach the convoy which has now been under steady attack for four days—we found her at least, in the pitch darkness of 2:00 in the morning. She has now lost sixteen ships, and everyone feeling mighty tense as we took up screening position. Thick and miserable fog closed in on us at dawn, and we are going to have one great time hanging on to this convoy.”

HMT Awatea at full steam ahead. The troop ship was lost in November 1942 after completing its mission delivering troops for the invasion of North Africa. [SS Maritime Website]

“We felt very helpless right in alongside her with her towering over us, and her decks crammed with thousands of soldiers in lifebelts, prepared to go over the side. She was making slow speed ahead of some four knots…praying that the watertight bulkheads would hold.”

The ship made it, but was among several troop carriers sunk after it had delivered its load during the invasion of North Africa the following November.

On Tuesday, Sept. 22, Kamsack’s crew got news of the sinking of HMCS Ottawa off Newfoundland. “Everyone feeling pretty grim, many of the fellows having close buddies on the Ottawa,” wrote Curry.

“Most of her crew went to the bottom with her when she caught two fish. Night closed in on us, icy cold, dark and rough…. what a miserable existence.”

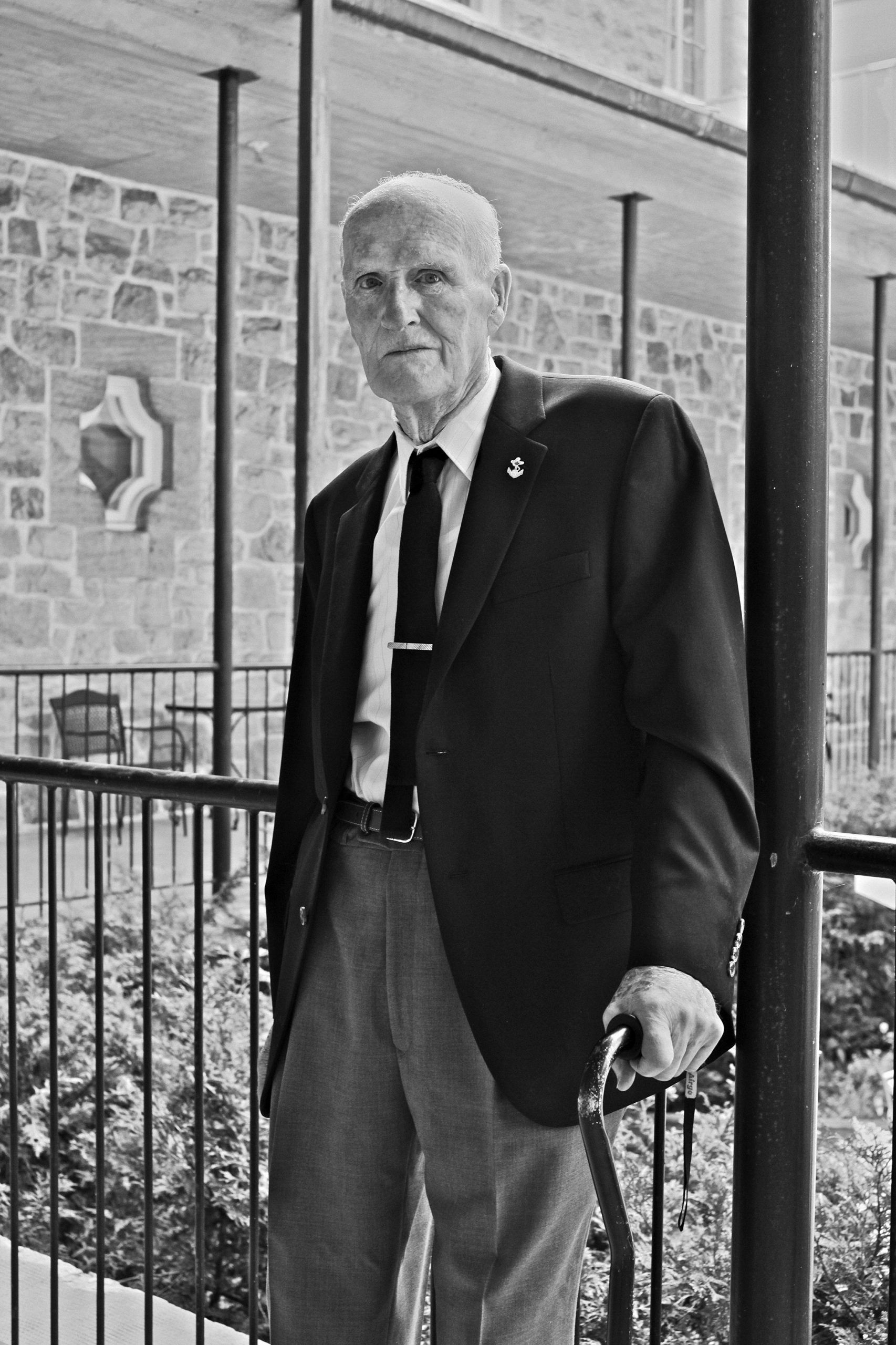

Francis Curry.

On Wednesday, Sept. 23, Curry “picked up a sub contact just at midnight.”

“We held on to it for a good hour, running in on it for five separate attacks,” Curry wrote. “We gave it over forty depth charges, and we felt satisfied that whatever it was, it took quite a beating.”

Some 294 Flower-class corvettes served with various navies during the war; 33 were lost, 22 of them to U-boats.

“It was a ship that came, more than any other, to symbolize trials and final triumph in the Battle of the Atlantic,” Larry D. Rose wrote in his book Ten Decisions: Canada’s Best, Worst, and Most Far-Reaching Decisions of the Second World War.

By war’s end, Rose said, Canadian navy brass were no more in love with the corvettes than they were at the beginning, and were more than happy to be rid of them. Today, all that remains of one of the Battle of the Atlantic’s most iconic symbols is a single vessel—HMCS Sackville, tied up on the Halifax waterfront a few months a year.

Frank Curry survived the war and went on to gain fame walking the world before he died in Ottawa, a day shy of his 94th birthday, in January 2014.

Frank Curry photographed in his later years. [Chartwell Retirement]

“I know I will never forget these days and nights.”

Rest assured, he never did.

Advertisement