Disabled war veterans relax at a Toronto hospital in 1916. [City of Toronto Archives/The Vimy Foundation]

One hundred years ago, the Pension Act came into effect, creating the framework for helping Canada’s disabled veterans. It is still in effect today, serving Second World War, Korean War, Royal Canadian Mounted Police and those regular force veterans who applied for benefits prior to 2006.

The Pension Act filled a void and was the way in which Prime Minister Robert Borden fulfilled a promise he made to the troops in the Canadian Corps in April 1917, shortly before the heroic capture of Vimy Ridge in France.

“The government and the country will consider it their first duty to see that a proper appreciation of your efforts and of your courage is brought to the notice of the people at home,” he said. “No man, whether he goes back or whether he remains in Flanders, will have just cause to reproach the government for having broken faith with the men who won and the men who died.”

The promise was made without really knowing what “a proper appreciation” would mean. The Conservative government of Borden, and later his Union government after 1917, was overwhelmed with the impact of the First World War on Canada. Out of a country of less than 7.8 million, 620,000 men and women enlisted for war service. Of them, approximately 66,600 were killed and more than 172,000 were wounded or disabled.

Canada had no formal pension process. Veterans of the War of 1812, the Northwest Rebellion and the Fenian raids had been paid in scrip, which could be used to buy land to start farms and homesteads in what, at the time, seemed like Canada’s infinite amount of unused land. What pensions there were often depended on rank and political favour.

The badge of the Great War Veterans Association was worn by members.[CWM/20060154-003]

With so many men signing up for service, the families they left behind were the first to show need.

In August 1914, Sir Herbert Ames, a wealthy Montreal businessman and member of Parliament, established the Canadian Patriotic Fund to assist families of serving men and those returning from the war with disabilities.

A network of volunteers was established to visit homes and assess the level of need. A wife could receive $5 to $10 a month with an extra $1.50 to $6 for each child.

These volunteers were social workers who dispensed advice, whether it was asked for or not, on budgeting, child care, nutrition and personal hygiene. It was done with high moral standards. Any household deemed unworthy could be cut off without appeal.

In 1915, the government created the Military Hospitals Commission to serve wounded and ill veterans. Senator James Lougheed, the government’s leader in the Senate, was the minister responsible. Buildings were acquired and converted to hospitals. A factory in Toronto was built to produce prostheses.

Veterans returning with tuberculosis were sent to sanitoriums.

The public had sympathy for those returning who were blind or missing limbs, but those with mental-health issues, then called shell shock, were left to their families for care. If there was no family or the family could not handle them, they could be sent to institutions for the mentally ill or intellectually challenged.

Senior members of the Amputations Association of the Great War, later the War Amputations of Canada, meet for a convention in Vancouver in 1932. [City of Vancouver Archives/99-4257]

The real concern of the government was that all these returning soldiers should integrate back into civilian life, return to their jobs and resume making a living for themselves.

There would be pensions for those with a disability caused by their military service, but these would be to assist while the veteran returned to his old work if possible. If not, retraining would be available at no cost to the veteran.

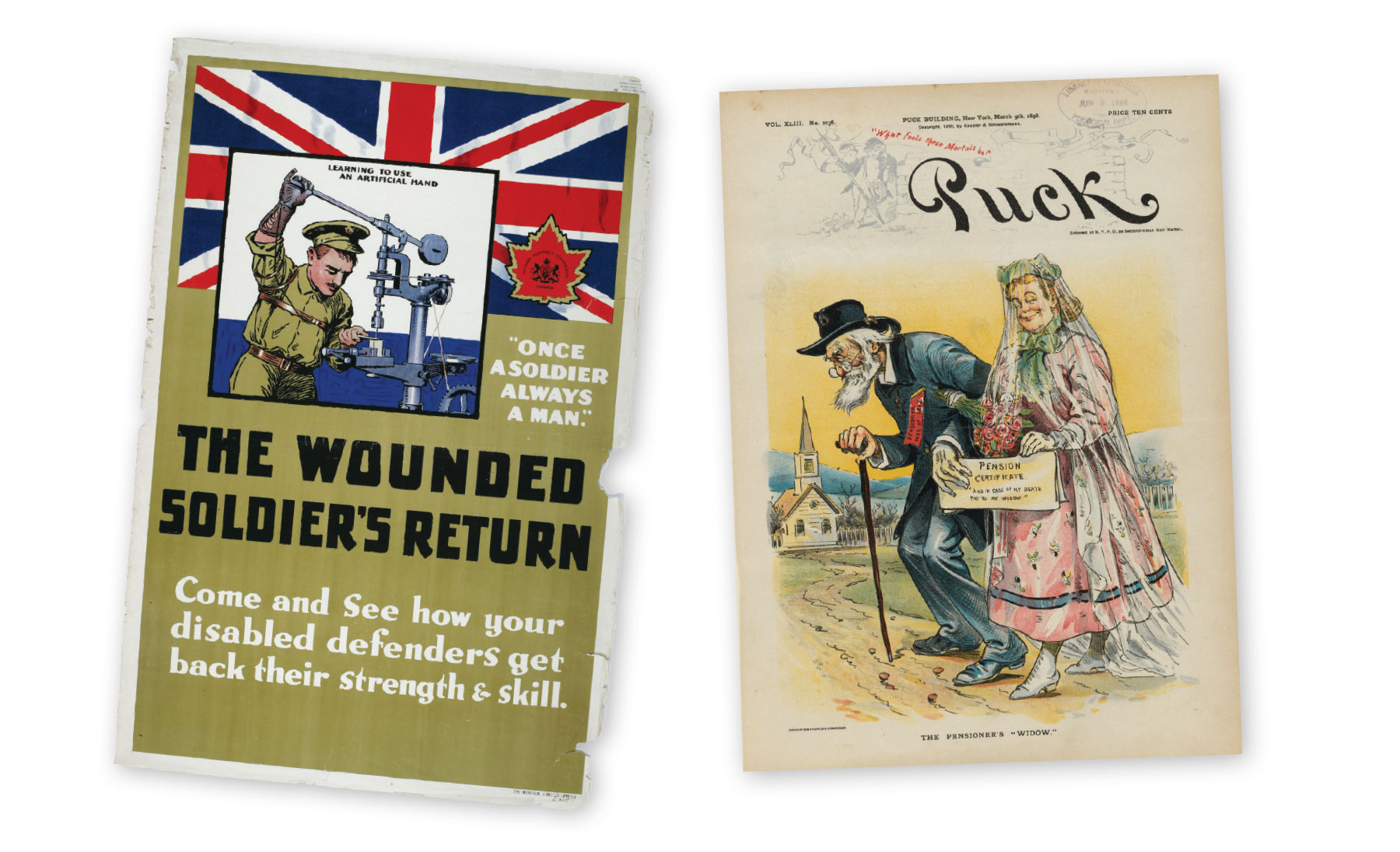

The philosophy was summed up in an information poster produced by the Military Hospitals Commission entitled “What every disabled soldier should know.” It is filled with optimistic, even inspirational maxims, such as:

• That there is no such word as ‘impossible’ in his dictionary.

• That his natural ambition to earn a good living can be fulfilled.

• That the Canadian Army Medical Corps and the Military Hospitals Commission exist to help him in doing this.

• That he must help them to

help him.

• That he will have the most careful and effective treatment known to science.

• That if his disability prevents him from returning to his old work, he will receive free training for a new occupation.

• That his own willpower and determination will enable him to succeed.

Tucked into the list of promises was “That every man disabled by service will receive a pension or gratuity in proportion to his disability.”

Canada had never been down that road before. It needed to look elsewhere to see what worked and what did not. The United States had been through the Civil War more than 50 years earlier and it was still paying out pensions. Borden dispatched Lieutenant-Colonel George Adami, a professor of pathology at McGill University in Montreal, to Washington to study military pensions there.

One of the problems the Canadian government feared was “pension widows,” women who had married aging veterans and were entitled to a lifelong pension after the husband died. The last surviving American soldier of the War of 1812 died in 1905, but the government was still paying pensions to surviving widows from that war. The last widow of an 1812 veteran died during the Korean War.

Major John Todd, a medical officer and a professor at McGill, looked at military pensions in other countries. During the war, he was assigned to the Pensions and Claims Board in England, which was chaired by businessman Sir Montagu Allan.

Writing back to Canada, Todd said, “The biggest thing in Canada at the present time is the whole pension question. If it is not removed from politics and put in the hands of a commission of about three men, we shall have pension trouble in Canada that, for our size, will make that of the U.S.A. look like a beginner.”

Todd saw how the French allowed its veterans to earn money on top of their pensions as an incentive to work, while in Britain pensions were decreased as recipients increased their earnings. This he saw as an incentive to idleness.

Todd believed that pensions should compensate disability and not loss of income. There needed to be practical guidelines. France had established a table of disabilities based on science. A 100 per cent disability would be granted in cases of loss of both arms or both legs or eyes. A single eye or a lower leg was a 40 per cent disability. Loss of reproductive organs was valued at 60 per cent.

Todd produced a report suggesting a system that was devoid of emotional consideration or patronage. Allan sent it to Ottawa where a parliamentary committee was wrestling with the same issues.

The report was accepted virtually in its entirety and on June 3, 1916, a three-person Board of Pension Commissioners was created. The commission was chaired by Montreal millionaire J.K.L. Ross with Todd and Lt.-Col. R.H. Labatt, a member of the wealthy brewery family, as the other two commissioners.

The commission set up an office in Ottawa and hired medical professionals to examine doctors’ reports and compare them with the applicant’s medical record. Historian Desmond Morton notes that the examiners “could also check for any pre-enlistment disability or hints of misconduct.” As an example, he writes that the widow of a soldier who drowned was denied a pension because the soldier had been swimming out of bounds.

“By 1917, Todd had established a system to save Canada from its own ‘pension evil,’ wrote Morton. “If Parliament gave Canadian soldiers the highest pension rates in the world, Todd made generosity cheap. Barely five per cent of pensioners ever qualified as 100 per cent disabled; the great majority were rated under 25 per cent.”

It was not long before veterans realized the system was too adversarial and began organizing.

Politicians of all stripes were anxious to court veterans’ favour but found themselves listening to a myriad of different opinions. There was the Army and Navy Veterans in Canada, the forerunners to the Army, Navy and Air Force Veterans of Canada (ANAVETS) but there were also dozens of regimental associations, which all drew up their own list of priorities. The War Amputations of Canada had formed to look after the specific needs of those who had lost limbs. In the sanitoriums, the tuberculous veterans were forming a network of chapters.

By 1917, a parliamentary committee had heard from various veterans’ stakeholders. Raising the amount of pensions was the only consistent goal among those who appeared.

Earlier that year, the Great War Veterans Association (GWVA) was formed. It quickly became the largest veterans group and would eventually join in the unification of many of these veterans organizations to create what is now The Royal Canadian Legion.

Posters showing disabled veterans returning to work after retraining were common after the war. A cartoon (right) shows an elderly pensioner of the War of 1812 with a much younger women in a wedding dress heading to church. Between them, they hold a pension certificate which reads, “In case of my death, pay to my widow.” [CWM/19900076-845; Library of Congress/2012647521]

By 1918, the Military Hospitals Commission had become the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Re-establishment with Lougheed as the minister responsible. From it would eventually emerge the Department of Veterans Affairs during the Second World War.

With the Armistice, Parliament felt it needed to pass legislation to enshrine its pension system. A special committee was formed. By this point, the GWVA, with its dynamic secretary-treasurer Grant MacNeil, had gained in numbers and was granted status at the hearing and allowed to call witnesses and question them.

The GWVA, which did not recognize rank among its members, was demanding that pensions be equal no matter what rank the veteran had while in service.

The Pension Board’s lawyer, Kenneth Archibald, drafted the legislation, which ran 30 pages and formalized much of what was already in place. The legislation was brought before Parliament in June and it passed before the summer recess, coming into effect on Sept. 1.

John Todd was a researcher and professor at McGill University when he was appointed a pension commissioner in 1916. [Wikimedia]

A fully disabled private would receive $720 a year, a widow $570 and a first child $180. “Until December, when the U.S. Congress raised American disability rates to a maximum of $1,200, Canadian rates were the highest in the world,” wrote Morton.

The Board of Pension Commissioners was now the Pension Board. The commissioners still had the final say. An appeal board was considered too costly and unnecessary.

Lt.-Col. John Thompson was the new chair but proved to be as frugal as his predecessors. The high moral tone remained intact. One widow was stripped of her pension when she took in a male boarder.

The Pension Act was now law, but it was far from perfect. MacNeil accused the board of being biased. When the Liberal Party under Mackenzie King came to power in 1921, it answered the veterans’ complaints with a Royal Commission on Pensions, chaired by cabinet minister and distinguished war leader James Ralston. His damning report in 1924 led to changes, including a proper appeals system and the creation of what is now the Bureau of Pension Advocates.

The Pension Act has survived, with many amendments, for 100 years. Although modern veterans are covered under the Veterans Well-being Act, the Pension Act will always be seen as the starting point.

Advertisement