During the War of 1812, the disastrous defeat that led to

First Nations Confederacy leader Tecumseh’s death

resulted as much from his ally Major-General Henry Procter’s

incompetence as from American fighting skill.

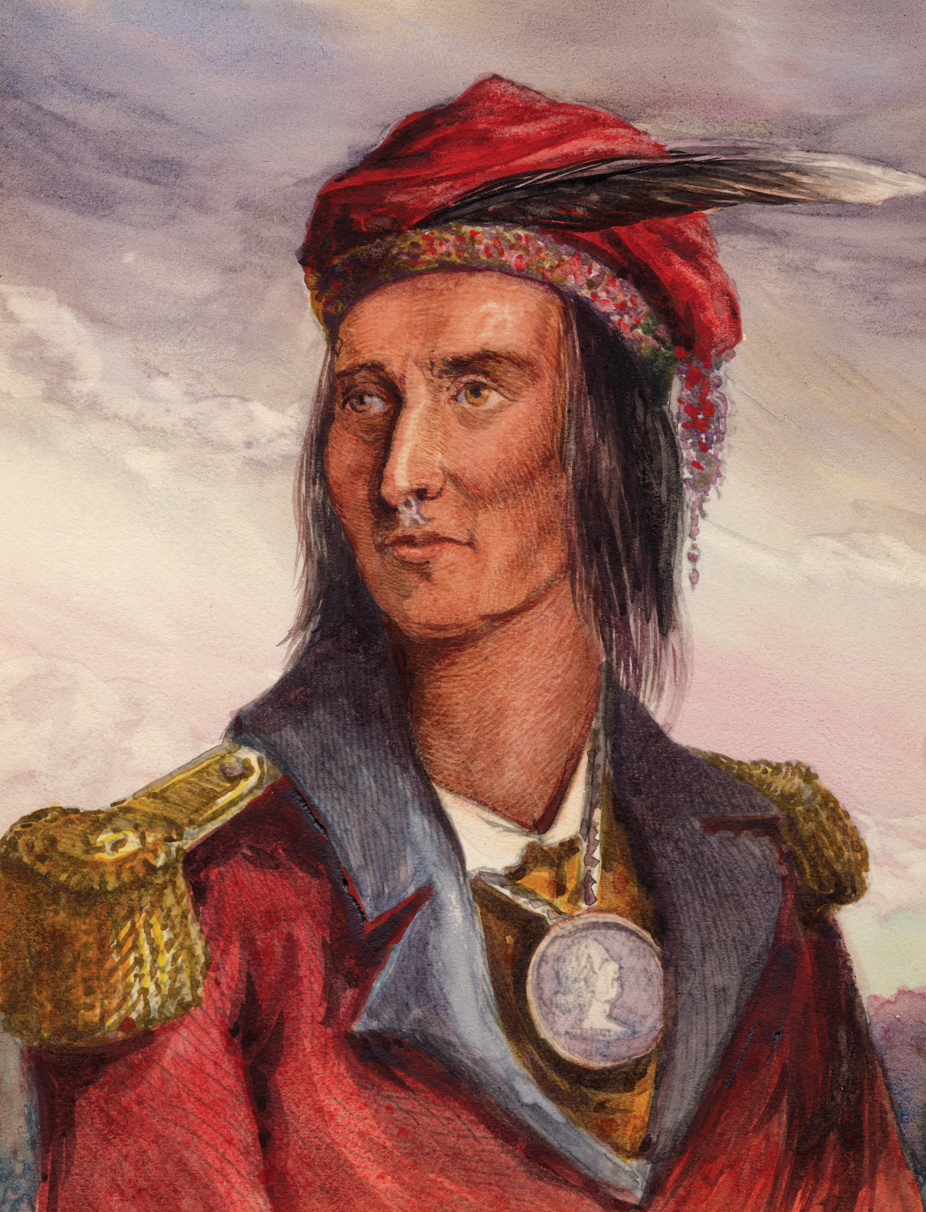

Before the War of 1812, American westward settlement flooded across many First Nations tribes’ traditional lands. Shawnee Chief Tecumseh spent years tirelessly building a First Nations confederacy to block further expansion. In an 1810 letter to Indiana Governor William Henry Harrison, the 43-year-old Tecumseh declared that the “only way to stop this evil is for all…red men to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land…. Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the clouds and the great sea, as well as the earth?”

By war’s outbreak unceasing fighting had greatly diminished Tecumseh’s confederacy. Allying with the British, Tecumseh shifted his warriors to Upper Canada where Major-General Isaac Brock declared him “the Wellington of the Indians. A more sagacious or more gallant warrior does not, I believe, exist.”

After Brock’s death at Queenston Heights, Tecumseh reinforced the British garrison at Amherstburg in western Upper Canada where Major-General Henry Procter commanded. While Tecumseh had lionized Brock, he disdained Procter. Meanwhile, now-Brigadier-General William Harrison sought to liberate Fort Detroit. Although Procter and Tecumseh fought the Americans to a stalemate, the ensuing defeat of Lake Erie’s British naval squadron convinced Procter to retreat from Amherstburg to

Lake Ontario’s Fort George.

Knowing this withdrawal would doom the First Nations confederacy, Tecumseh argued that the British had promised “to get us our lands back, which the Americans had taken from us…. You always told us you would never draw your foot off British ground….Listen! The Americans have not yet defeated us by land…we therefore wish to remain here, and fight our enemy…. If they defeat us, we will then retreat [with you].”

Procter finally won Tecumseh’s consent for a limited withdrawal to the Lower Thames River. On September 24, 1813, Tecumseh and his warriors accompanied the retreating nearly 1,000-strong British force. Harrison pursued with 3,000 troops and 500 Kentucky cavalry and overtook the retreating column at Moraviantown on Oct. 5. Procter deployed his men poorly and ordered Tecumseh’s warriors to stay to the extreme right in a swampy forest. This meant neither soldiers nor warriors supported each other. When the British line was easily shattered, the Kentucky cavalry turned on Tecumseh’s warriors. Through the thunder of gunfire, Tecumseh’s voice was heard rallying his men to stand firm. But the warrior force was broken and fled. The Americans found Tecumseh’s bullet-riddled body. With his death, the First Nations confederacy was

forever broken.

When the War of 1812 began, Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Procter had been commanding the 41st Regiment of Foot in Upper Canada for 10 years and was considered a competent peacetime commander. This led Major-General Isaac Brock to place the 49-year-old officer in charge of the Amherstburg garrison with orders to prevent American incursions from Fort Detroit into western Upper Canada.

Launching a skirmishing campaign, Procter kept the Americans off balance until Brock and Tecumseh arrived and captured Fort Detroit. Procter was soon promoted to major-general, retaining command in Amherstburg. Although somewhat successful in several subsequent campaigns, none proved decisive and the American threat to the region kept growing. When Tecumseh joined the fight, the two men were unable to agree on a coherent strategy. As the British situation deteriorated due to the naval defeat on Lake Erie, Procter ordered a retreat. Convinced the Americans could not defeat them, Tecumseh vehemently opposed this.

If western Upper Canada could be held long enough, Tecumseh believed that reinforcements from the east could still save the day.

Procter insisted on withdrawing to the Lower Thames River. By this time, Procter’s command was a shambles. Morale was poor and Procter had proven an uninspiring wartime leader. The retreat—with the British relying on heavily burdened carts dragged by oxen and cattle—was slow and gruelling.

When the Americans overtook the column on October 5, Procter deployed as if on a European battlefield with two lines standing in the open across the roadway fronting Moraviantown. No trenches were dug or abattis emplaced before the troops. Swampy ground in the centre meant the British line was divided into two groups.

As for Tecumseh’s warriors, Procter decided their guerilla-style of fighting would disrupt his orderly line and consigned them to a swampy wood to his right. Procter and his staff mounted horses and awaited the expected orderly advance of American infantry.

Instead, the Kentucky cavalry charged, sliced through the British centre and then rolled up the flanks. Most of Procter’s command surrendered while he galloped away. Only 246 men reached Lake Ontario’s Fort George. Procter’s career was ruined. Court martialed, he was found guilty of four charges for his conduct during the retreat and battle. Procter returned to England in 1815 and entered forced retirement. He died on Oct. 31, 1822–a little over nine years after the battle.

Advertisement