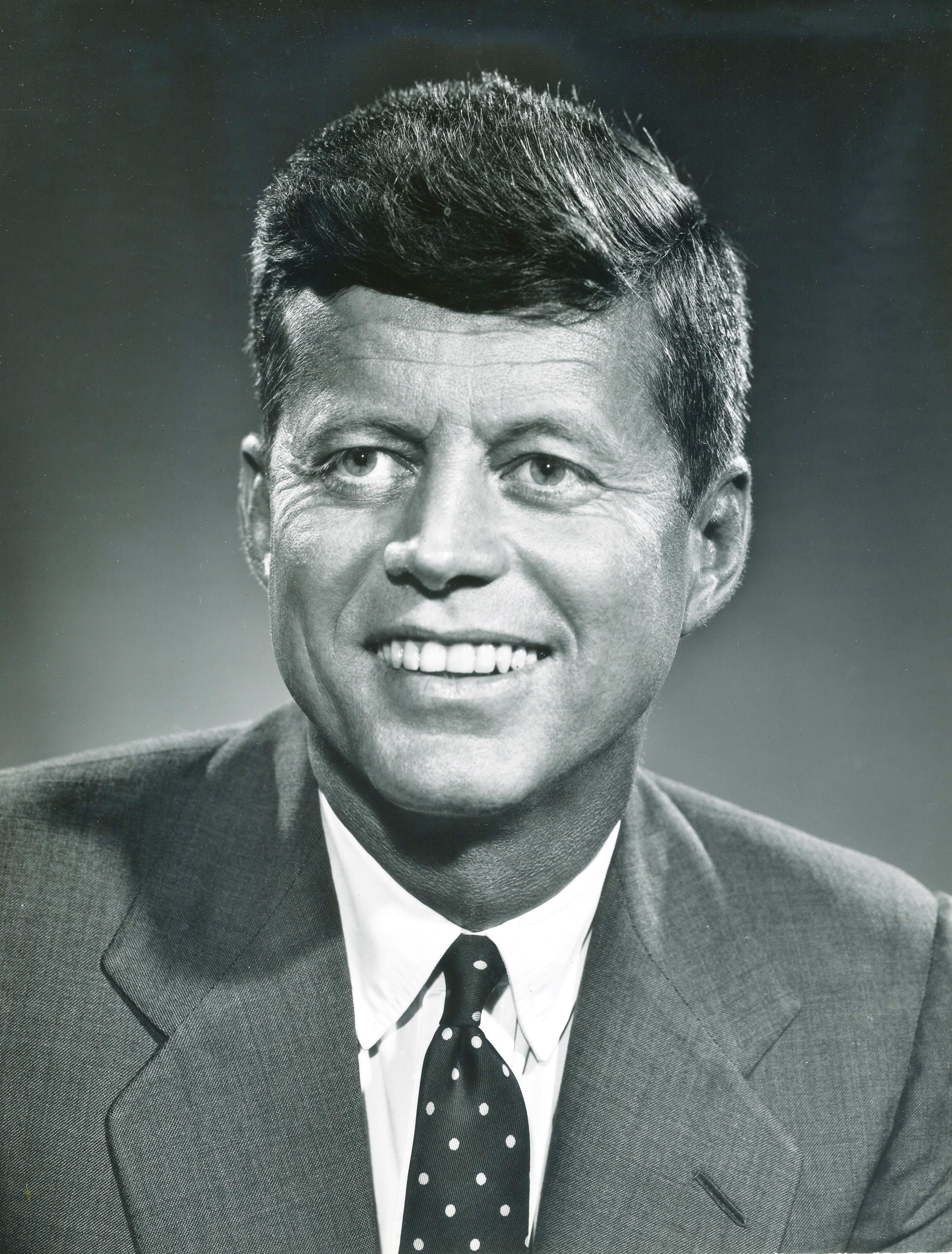

For 13 days in October 1962, the

world stood on the precipice of

nuclear Armageddon as President

John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier

Nikita Khrushchev squared off

during the Cuban missile crisis

On Jan. 20, 1961, newly inaugurated President John F. Kennedy inherited an ill-conceived plan to overthrow Fidel Castro’s Cuban regime through an invasion by exiles, backed by the Central Intelligence Agency. Launched on April 17, the Bay of Pigs fiasco scuttled any hope for diplomatic rapprochement between the two countries. With Cuba just 145 kilometres from Florida, Kennedy’s administration considered Castro’s government a threat. On Oct. 16, this seemed proved when a U-2 spy plane photographed Soviet-built sites deploying between 16 and 32 nuclear missiles. Kennedy’s advisers proposed two responses: outright invasion or naval blockade.

Advised that air strikes alone could not guarantee missile elimination, Kennedy wrote Khrushchev on Oct. 22. “I have not assumed that you or any other sane man would, in this nuclear age, deliberately plunge the world into war which it is crystal clear no country could win and which could only result in catastrophic consequences to the whole world.” That night Kennedy revealed the crisis on television, demanding that the missiles be withdrawn and imposing a naval quarantine around Cuba.

“I have not assumed

that you or any other

sane man would,

in this nuclear age,

deliberately plunge the

world into war which

it is crystal clear no

country could win…”

The following day, U.S. naval ships deployed, Soviet submarines hovered nearby, and freighters bound for Cuba with military supplies heaved to—except for an oil tanker. When Kennedy urged Khrushchev to halt all the ships, the Soviet premier replied that he would not be intimidated. While the two nations wrangled before the United Nations (UN) Security Council on Oct. 25, Khrushchev quietly recalled the freighters and the U.S. allowed the oil tanker through the quarantine.

On Oct. 26, the crisis peaked with aerial photos showing accelerated construction at the missile sites and Soviet IL-28 bombers being uncrated at Cuban airfields. But the Soviet premier had already blinked and offered concessions—it would remove the missiles if the U.S. lifted the quarantine and agreed not to invade Cuba.

The following day, Oct. 27, Khrushchev also demanded that the U.S. remove its Jupiter nuclear missiles from Turkey. Kennedy, meanwhile, withstood pressure to approve air strikes on the sites while responding favourably to the less provocative Oct. 26 offer.

Then, late that night, Robert Kennedy met secretly with the Soviet ambassador. Agreement was reached to end the crisis on the Soviet terms—including eventual removal of the missiles from Turkey. On Oct. 28, Radio Moscow announced acceptance of the solution.

In May 1961, following the Bay of Pigs invasion, Khrushchev proposed situating intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Cuba both to counter the American lead in building and deploying strategic missiles and to protect Cuba from further American-sponsored invasion. If communist Cuba were lost, Khrushchev reasoned, Soviet “prestige in Latin America would diminish.” Countries would think the Soviet Union only able to “make empty proclamations, threats and speeches in the UN.”

Believing the Americans would acquiesce to his brinkmanship, Khrushchev accepted the potential for nuclear war. He also realized most of the missiles would be intercepted before they could launch. However, “even if only one or two nuclear bombs reached New York City, there would be little of it left. We would have a balance of fear.”

The Soviet operation went beyond just deploying missiles. A strong protection force of 40,000 to 50,000 was sent, as were IL-28 nuclear-capable bombers, MIG-21 fighters, more than 100 battlefield nuclear weapons, and nuclear submarines. What had begun as a deterrent was, by the time the U.S. spy plane unmasked it, a military force prepared to fight a nuclear war.

With more than 200 U.S. naval ships blockading Cuba, Khrushchev sought to retain the upper hand on Oct. 24 by accusing Kennedy of “not declaring a quarantine, but rather…setting forth an ultimatum and threatening that if we do not give in to your demands you will use force.…You are no longer appealing to reason, but wish to intimidate us.” Khrushchev warned that the Soviets “will not simply be bystanders…to piratical acts by American ships on the high seas. We will…take the measures we consider necessary and adequate…to protect our rights.”

If communist Cuba were

lost, Khrushchev reasoned,

Soviet “prestige in Latin

America would diminish.”

Three days later, with American force buildups at home and in Europe, Khrushchev realized events were spiralling out of control. A letter from Castro on Oct. 26 warned that invasion was imminent and called on the Soviets to respond with a nuclear first strike to “eliminate this danger forever…However harsh and terrible the solution, there would be no other.”

Deeply alarmed, Khrushchev immediately wrote Kennedy. While arguing that American concern over the missiles was groundless, Khrushchev hinted at being willing to withdraw them if the blockade was lifted and the U.S. pledged not to invade Cuba.

In a curious twist, the man who had risked Armageddon now offered a peaceful resolution. Although it required the Soviet Union to clearly back down, it did provide some face-saving measure—in particular the withdrawal of American missiles from Turkey.

Advertisement