Painter Marc Magee depicts HMCS Trentonian. The corvette was torpedoed by U-1004 and sunk in February 1945. [Marc Magee]

A pair of portholes are grim reminders of destruction during the Battle of the Atlantic

The mangled portholes, bronze bent from the force of the explosion, “are the real story of the sinking of the Trentonian,” said Canadian naval historian and author Roger Litwiller in an interview with Legion Magazine. He donated the two artifacts from the ship to a pair of Canadian museums in late 2021.

The Royal Canadian Navy modified Flower-class ship was the last corvette sunk during the Second World War’s Battle of the Atlantic. On Feb. 22, 1945, it was escorting a convoy in the English Channel when it was torpedoed and sunk by German submarine U-1004 just 20 kilometres from Falmouth on England’s southern coast.

“The torpedo struck us aft with a terrific explosion and the corvette went down in 10 minutes,” said navigating officer Lieutenant Ralph Abbott, in a newspaper account at the time. After destroying the charts, he abandoned ship. “Some of the men sang while awaiting rescue,” but Abbott had to swim for about 45 minutes before rescuers arrived.

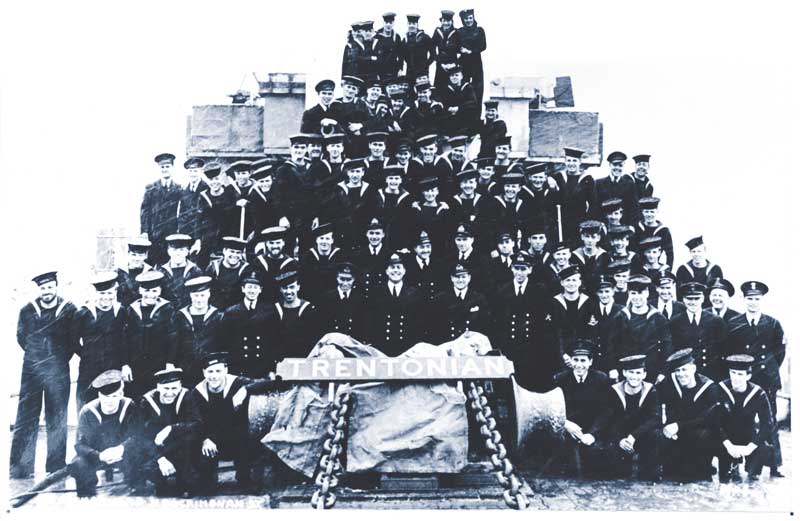

The survivors, including a number of wounded, were picked up by motor launches. Six of the 101 crewmen died.

The corvette was torpedoed by U-1004 and sunk in February 1945. One of two recently recovered mangled portholes show the power of the attack.[Courtesy Roger Litwiller]

“My biggest fear is artifacts like this can end up as a lawn ornament in somebody’s garden or sitting in a scrap heap to be melted down.”

—Roger Litwiller

The wreck lay scattered over the sea floor some 50-plus-metres deep, undisturbed for decades, providing habitat for fish and marine plants. But recently it has attracted recreational divers.

In May 2021, Litwiller, author of White Ensign Flying: Corvette HMCS Trentonian, was contacted by the president of a British diving club. Although the club’s members had been warned of the British law protecting undersea wreckage of Second World War ships and aircraft, many of which are considered gravesites, two of the club’s divers had retrieved portholes from Trentonian.

The club was unable to safely return the artifacts to the wreck site, so the president went searching for a home for the historic items and offered them to Litwiller. He accepted them.

After receiving the portholes in the mail, Litwiller donated them to two museums—one to the Naval Museum of Halifax, as Trentonian had sailed from the city’s port early in its service, and the second to the Marine Museum of the Great Lakes in Kingston, Ont. It was here at this former shipyard on Lake Ontario (now a national historic site) that shipwrights crafted the corvette.

Said Litwiller: “Artifacts like these are of such huge historic significance.”

Crew of Trentonian circa 1944. Six of 101 on board died when it was sunk a year later. [Naval Museum of Halifax]

Advertisement