Soldiers and sailors practice the D-Day invasion from a landing craft, Portsmouth, England, May 1944. [E.T. HEATHCOTE, TESTAMENTS OF HONOUR—G0383]

On the eve of the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, prepared two statements about Operation Overlord, the assault on Fortress Europe. Despite the horrendous weather, Eisenhower gave the go-ahead, delaying the landings for one day. We know the eventual result, but it is worth remembering how Eisenhower pondered the real possibility that Overlord would fail, and that he would have to withdraw his forces. In the message he wrote but never used, Eisenhower said, “My decision to attack at this time and place was based upon the best information available.”

“Time and place.” A crucial phrase, for only in 1944 did Eisenhower have operational and strategic control over the many elements that would make Overlord a success. The Allies then dominated the sea lanes and the skies above Western Europe in ways that would have been difficult to comprehend even a year earlier.

Whatever the wisdom of committing so many troops to the Mediterranean, their operations toward Rome in May 1944 kept the German Tenth Army occupied. The Soviets, having turned the tide in the east, also opened offensives that summer to press the Germans further. Eisenhower could control such things, but only by 1944.

The pace of technology and the sheer weight of numbers had also reached a tipping point by 1944. To take one example, the operational range of fighter aircraft limited the role of airpower over Dieppe in August 1942. Normandy was twice as far from England as Dieppe, but the longer range of aircraft available in 1944 meant that air power could have much greater effect than ever before. By May 1944, there were nearly 3 million Allied troops waiting in southern England for Eisenhower’s signal. Behind them were countless depots filled with massive supplies of food, equipment, fuel and munitions. More than 4,000 ships and 1,200 aircraft lay in waiting. Such a buildup was only attainable by 1944.

The weight of strategy, technology and numbers dictated an invasion sometime in 1944, but the specific timings for Overlord still hung on factors beyond Eisenhower’s control. As the Canadians knew from Dieppe, planning a cross-channel assault meant confronting narrow windows dictated by the seasons, the weather, distance and geography. Only on certain nights could such an immense flotilla sail through the English Channel undetected; tidal charts dictated the ideal times to land. That information was no secret. The very things that made the specific timings so crucial also made the operation so risky. Indeed, Eisenhower’s decision to go ahead with the invasion in spite of the weather offered him a crucial edge over the Germans.

Of course, much did not go according to plan. The airborne landings on both flanks went dangerously awry. On Juno Beach and, especially on Omaha Beach, the preliminary aerial and naval bombardments largely missed their targets; the tanks arrived late, or not at all. That left thousands of young men to storm the beaches against German positions that remained largely intact. But they gained a foothold, allowing the vast forces behind them to force a bridgehead. Such an operation could only have come in 1944, but even with the “best information available,” it was still a near-run thing.

D-Day was supposed to be May 1, 1944, or as close to that date as possible. That was the choice of the men who planned Operation Overlord because climate records promised the likelihood of good weather and a May landing would allow the maximum possible time to defeat the German armies before winter.

The views of the planners were accepted by the American and British chiefs of staff at the Quadrant Conference in Quebec City in August 1943 and confirmed at the Tehran Conference in November, when Josef Stalin and Franklin Roosevelt resisted Winston Churchill’s attempts to postpone Overlord to pursue opportunities in the Mediterranean.

Churchill refused to take this decision as final, arguing that the invasion of France could be launched as late as July while landing ships, vital for any seaborne assault, remained in Italy to carry out an end run around the German defences at Casino. Through persistence, he won approval for Operation Shingle, the landings at Anzio in mid-January 1944, forcing a month-long delay of D-Day.

Counter-factual history can never provide definite answers, but a comparison of the circumstances of early May and early June certainly offers food for thought. The weather in June forced General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, to postpone D-Day for 24 hours and rely on a weather forecast that indicated a calmer period on the morning of June 6. The airborne divisions that took off on the night of June 5-6 met strong winds and the troops were widely scattered. Cloud cover on the Normandy coast forced the U.S. Army Air Forces heavies to delay their bomb release, leaving the beach defences intact. British and American fighter bombers were also hampered by the weather conditions and failed to locate their targets. Seasick soldiers added to the misery and strong offshore winds forced battalions such as the Queen’s Own Rifles to land in front of a resistance nest instead of the flank. The guns of the field artillery, aiming to keep enemy heads down during the run-in, fired from pitching landing craft and could not concentrate their fire. It was up to the infantry, supported by the amphibious duplex-drive “swimming tanks,” to overcome the beach defences delaying the advance inland.

These problems were bad enough at Juno Beach and the British beaches, but it was the near-disaster at Omaha Beach that best illustrates the difficulties of June 6.

The Omaha defences were to be neutralized by B-17s and B-24s and the American General Omar Bradley based his plan on their ability to succeed. The landings at Omaha began shortly after the bombing ended, leaving little time for the navy to target the pillboxes.

The first week of May 1944 presents a very different picture. A high-pressure ridge had settled over southern England and the west of France, bringing sunshine and calm seas. The enemy’s defences were less advanced than in June, but the 352nd Division had been part of the forward defences of Gold and Omaha since March, so Omaha would not have been a walkover in May. Everything else would have gone better and with an extra month to win the battles in France and Belgium, the Allies might have crossed the Rhine in 1944.

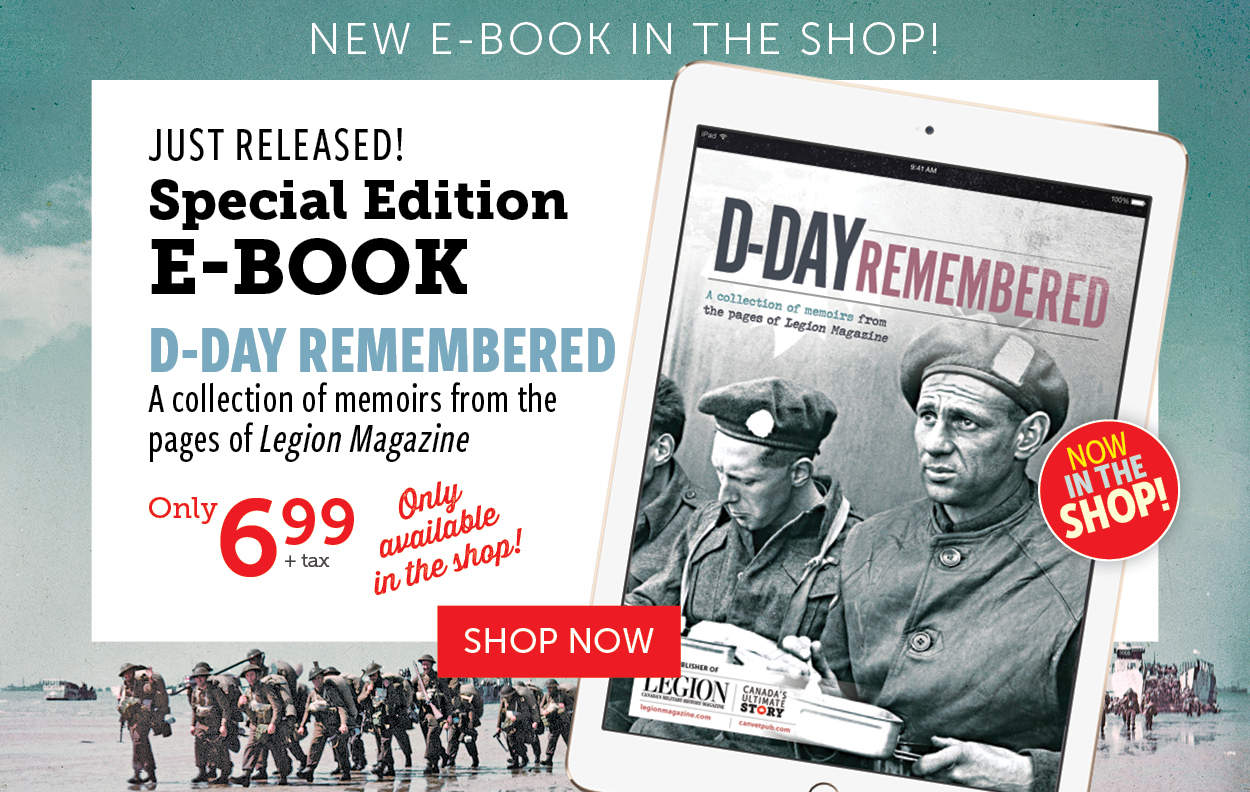

Advertisement