PART ONE:

Aboard HMCS Toronto on Operation Reassurance, Investigating the Possibility of World War III.

One hundred years after The Great War lit the world on fire and killed tens of millions, a strange combination of threats has once again pushed the allied countries toward greater conflict. And we are not immune. On the Iraq front, Canada’s fighter jets are bombing Islamic militants in Fallujah and JTF2 commandos are training Kurdish Peshmerga in Erbil. On the Russian front, The Royal Canadian Regiment has deployed to Poland, more CF-18s are flying out of Lithuania and HMCS Toronto faced down attack jets in the Black Sea. Russia wants a new empire, the Islamists want a new caliphate—countries are to be annexed, maps redrawn. How this will all turn out is impossible to guess, but the underlying threat is of widespread war. On the centenary of the First World War, the question must be asked: could it happen again?

—–—–—–—–—–—–

A photo of the Russian Sukhoi Su-24 as it buzzed HMCS Toronto in the Black Sea. [PHOTO: DEPARTMENT OF NATIONAL DEFENCE]

For reasons understood only dimly even now, the world spent the four years from 1914-18 doing its very best to destroy all it could. The logic of the war—whether it was justified, whether its conduct made any sense—seems to matter less as time passes. It now seems like a tsunami or an earthquake; an unavoidable disaster loosed upon us all.

But that’s not true, exactly. In the years leading up to 1914 there was an epic swell of small events and factors leading toward conflict (How The World Fell Over The Edge, July/August 2014). There were prideful monarchs, hawkish politicians and functionaries and on all fronts a combination of voracious nationalism and unrepentant exceptionalism. Beyond that, there were multiple conflict zones and areas of instability full of irredentist, militarist, ideological forces—all underpinned by a complex system of alliances; each piece a small cog in a great machine moving toward its own unravelling.

Nobody in the world wanted what they ended up getting from the First World War. Our forefathers stumbled into it, resolutely failing to predict the scope and horror of what was about to happen. To think we are any different is likely a mistake. That we now collectively lack the imagination or ability to foresee conflict is so obvious it may be easy to overlook. If you had asked Canadians on Sept. 10, 2001, if Canada would be deploying to war in Afghanistan next month and would stay militarily involved in the country until 2014, no one would have believed it.

Similarly, imagine having that same conversation a few months ago about Iraq, where Canada is now bombing a group of Islamic militants so vile that al-Qaida even disowned them.

There may not be an intention to start a war or even to cause conflict. But it isn’t necessary that one actor or more has a coherent intention, all that is required is that certain interests come into conflict in such a way that the situation can’t easily be de-escalated, either because of treaty commitments, domestic politics, actual national security concerns or all three.

The effect is that no single party is rushing toward war, nor even walking toward war, rather they are curiously sauntering toward danger.

Is it possible the same kind of mistakes that led to the First World War could be happening again?

Certainly there is enough potential for instability in the world. To the East there is the rise of China and the complicated antagonisms and alliance commitments between Taiwan, Japan and the United States. In Africa—and worldwide—there’s the possibility that the Ebola virus could somehow become uncontrollable. And looming over that is the ongoing collapse of Arab civilization and the resulting schism between Sunni and Shia Muslims that threatens to explode into a chaos affecting billions.

Then there is Vladimir Putin, the ex-KGB agent now in charge of Russia who seems determined to kick-start a new Russian empire by any means possible. Beginning with Russia’s outright annexation of Crimea last year, and continuing with the covert invasion and annexation of eastern Ukraine, Russian aggression has evidently begun and anyone who tells you they know where and when Putin will stop is guessing.

Among those now deeply concerned about Russia’s intentions is Prime Minister Stephen Harper himself, who has been unusually candid in his denunciations of Putin’s desire for a new empire. “Our duty is to stand firm in the face of Russian aggression,” was the title of an editorial Harper wrote for The Globe and Mail this past summer.

In the article, Harper derides the “criminal aggression and recklessness” of Russia and its proxies fighting in Ukraine. He says there “can be no weakening of our resolve to punish the Putin regime,” and that “Russia’s aggressive militarism and expansionism are a threat to more than just Ukraine; they are a threat to Europe, to the rule of law and to the values that bind Western nations. Canada will not stand idly by in the face of this threat.”

Harper concludes by evoking previous wars Canada has fought to defend its values, which is as stark a warning as you’d ever want to read in a national newspaper. Unless Russia backs down, he wrote, Canada and its allies will take further punitive steps against Russia because “the values and principles we cherish as Canadians, and for which so many generations have fought and died, demand it.”

While the overheated rhetoric is certainly flying, there are also more classical signs that the brinkmanship games have begun in earnest: the movement of men and arms into better position.

The current state of mobilization is almost entirely symbolic, at least on paper. Operation Reassurance is Canada’s contribution to the NATO mission attempting to deter Putin’s aggression by placing token amounts of soldiers, planes and ships in the line of his potential advance against NATO allies like Poland, Estonia and Lithuania.

Where the operation gets very real, however, is out where the symbols of our resistance to Putin actually stand face-to-face, missile-to-missile, with the Russians.

So that’s where I wanted to go. If the conflict was going to start, that’s where it would happen—on the Estonian border or in the sky over the Ukraine or on the Black Sea.

In August, HMCS Toronto entered the Black Sea as a part of the NATO effort alongside ships from Spain, Turkey, the U.S. and the Ukraine, among others.

HMCS Toronto was to be the canary in the coalmine. Or, put another way, a Canadian frigate in the Black Sea facing the Russians. A slight provocation to test the waters, you could say.

HMCS Toronto on patrol. [PHOTO: MASTER CORPORAL DAVID SINGLETON-BROWNE, DND]

It’s a Hot Move, Get Your War Bag

I joined up with Toronto just after she left the Black Sea, during a port visit on the Greek island of Crete in the Mediterranean.

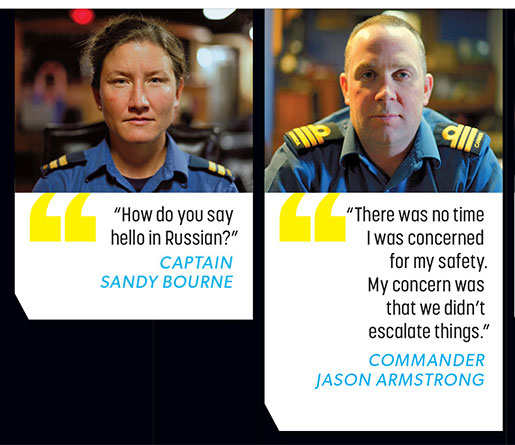

Life aboard a warship in the days that might be leading up to WW III is relaxed, even happy. The crew of 250-plus, led by Commander Jason Armstrong, initially give the impression of being engaged in a great adventure.

Not me, however. I come on board and immediately get sick. Apparently this is not uncommon. I’m sharing a bunk with the engineering officer, Lieutenant (N) Anthony Morash. At first he doesn’t say much, but I can tell he’s impressed with my ability to take naps. I have the top bunk. The bed is very nice; it’s about exactly as wide as my shoulders, so there’s lots of room. It’s surrounded by hard, sharp metal and the ceiling, which is a mass of pipes, wires and steel boxes, is about 18 inches above my pillow. The bunk is also more than five feet off the ground and there’s no ladder or any other obvious way to get into it except to try using the cabin’s office chair, which sits on well-greased wheels, so getting into bed is super easy and I do it gracefully every time.

My first morning aboard ship starts very suddenly and painfully when the speaker on the wall a foot from my head starts screeching at a shocking volume and I lurch up in surprise and smash my head directly into the metal ceiling.

“It’s a hot move,” the speaker warns me. “Get your war bag.” My head is ringing and I have no idea what that sentence meant. The sound volume is impressive though. On a ship that for the most part seems pretty old the sound system is a masterful work of acoustical engineering.

The ‘pipes,’ at least in my cabin, are so loud and clear that the effect is less like listening and more like having someone else’s thoughts ported directly into your brain at maximum amplification. At first it’s unpleasant, but over time it becomes reassuring: I’m constantly being told what’s happening and what to do—how to wear my sleeves (rolled), where the flight safety briefing will be and when (in the wardroom, 30 minutes) and how the ship performed on the last man-overboard drill (below fleet standard, unsatisfactory).

In any case, we soon get underway (that’s the hot move part) and as we do I tour the ship. With the exception of the 57-mm gun on the front deck, the ship doesn’t look particularly menacing as most of the weapons—various kinds of missiles, mostly—are kept out of sight beneath covers and my initial suspicion that we are somewhat under-equipped to fight the Russians is never quite dispelled.

I also can’t help noticing that there is a smell. They call it shipsmell, one word. It’s various kinds of fuel, paint and a blend of all the various odours the human body is capable of producing. Smell is the wrong word. It’s more like fumes. There are fumes. It’s like being inside a big machine.

I meet the ship’s captain, Commander Armstrong. He’s in his 40s, stocky and just generally comes across like a very competent hockey coach—good-humoured but imperious, precise in his demands and quick to reproach any appearance of weakness or confusion. Consequently, most of the junior officers tread very lightly around him.

During a surprise drill in the middle of that first night, I finally find out what a war bag is—a bunch of fire-retardant gear in a small pouch everyone carries around to avoid getting their faces burned off in a fire.

A Brief Detour Into History

While the actual causes of the First World War remain somewhat unclear, it is far easier to track the way it started, which could still be useful.

Life in Canada in the decade leading up to the outbreak of war was essentially oblivious to the roiling discontent in Serbia and Austria; two countries enmeshed in a long-standing conflict over who got to control the Balkans.

The details of that particular regional conflict are less important than the complex system of alliances that had been established over the long period of peace preceding the war.

That a pre-existing Serbian nationalist irredentism was exacerbated by the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina by the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1908 set the conditions for war six years later was probably easy to overlook at the time, but impossible to miss in retrospect.

As the conflict heated up, Russia stood with Serbia in a show of pan-Slavic pride and France stood with Russia. Britain was standing with Belgium and France. Naturally, we stood with Britain. In the same way, Germany had tied itself to the fading, almost defunct Austro-Hungarian Empire.

So when a Serbian assassinated Austrian prince Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo, Bosnia, in the summer of 1914 it set the stage for the First World War, which in this reading is essentially no different than the chain reaction that sets off a bench-clearing brawl.

Which is how it came to be—though it was a course never decided upon explicitly by anyone, anywhere—that the fate of young Canadian boys from such places as Moose Jaw, Sask., or Corner Brook, Nfld., was sealed by the conspiratorial activities of Serbian nationalists in Belgrade, consumed by the desire to retake Bosnia and re-establish the Serb empire over the Balkans.

Our current situation as a member of NATO is not dissimilar. Will we go to war over the Ukraine? No way. The territorial integrity of the Ukraine is clearly not a cornerstone of Canadian national defence. However, what about Estonia, Latvia or Poland? The answer there is less clear. Why will we go to war to protect Poland? Because we are in alliance with them and have pledged to treat an attack against them as an attack against us.

The alliance system works as a deterrent right up until the exact point that it stops working as a deterrent, at which point it works like a dragnet sucking all sorts of countries into doing things they really have no business doing.

That a country joins an alliance to bolster its own security is obvious, but that the alliance may drag you into conflicts that don’t impact your security is less obvious. And that sometimes those alliances will drag you into conflicts that undermine your security is something that should be considered.

HMCS Toronto sends out its boarding party during a patrol in the Mediterranean. [PHOTO: ADAM DAY]

The Black Sea Crusaders

Captain Armstrong knew this was going to be a historic mission. There hadn’t been a Canadian ship in the Black Sea since HMCS Gatineau in 1991 after the end of the Cold War. Before that, it had been many, many decades since a Canadian ship had been up that way, since before the Cold War really cranked up.

In August, Toronto sailed up past the Dardanelles, past Gallipoli and through Istanbul and the Straits. A few years ago, Armstrong and his second-in-command, Lieutenant-Commander Sheldon Gillis, had cubicles right beside each other in Ottawa and now they were standing beside each other on the bridge watching the Black Sea open up right in front of them.

This was Russia’s backyard. Armstrong had his mission: get in there and fly the flag to show NATO’s allies that the alliance was serious about protecting them. He knew two further things, however, which is that the Russians knew they were coming and that his actual primary mission was to avoid escalating the situation any further.

And the situation was pretty far from status quo. In early September, after Russia had annexed Crimea, they were conducting a proxy war against Ukraine in an attempt to secure more territory. Novorossiya, Putin was calling the eastern Ukraine: New Russia.

HMCS Toronto would be sailing to within about 50 kilometres of the coast, where Ukrainian ships were being fired upon—and sunk—by Russian-backed forces.

Sabre-rattling is a fine art. And when it’s a billion-dollar warship and the whole world is watching, the man doing the rattling needs a steady hand. “We knew we were going to interact with Russian air and sea assets,” said Armstrong, “And there’s always a risk. This is a risky business. But my concern was that we didn’t escalate things.”

On the morning of Sept. 7, that concern was put to the test. The first sign that something was up was the arrival of a Russian maritime patrol aircraft in the vicinity of the ship.

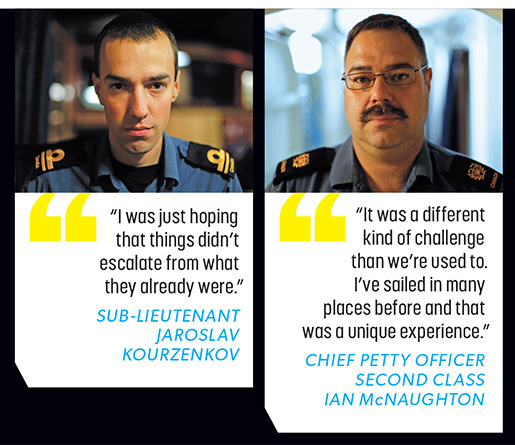

At that time, Toronto’s Sea King helicopter was in the air and so Armstrong made the call to assemble the special team they’d put together to deal with this situation. It was called the ICRT—inevitably dubbed the Iron Curtain Response Team—and when the call for the ICRT went out over the pipes everyone scrambled as the ship closed up.

Armstrong radioed the Russian aircraft and told them to maintain their distance. He issued a legal warning called a Safety of Flight Advisory, but he was careful how he did it, not specifying what distance to maintain, “because if I said 10 and he came 9, then I have to do something.”

The Russians didn’t respond on the radio, but shortly after the warning, Toronto picked up something even more provocative—incoming fighter jets, moving fast and right at them. “We tracked them all the way in,” said Armstrong. They didn’t know what the Russian intentions were, they just knew the fighters were coming and they had to wait to see what would happen. If the fighters were going to launch missiles, it would happen quickly and from a distance. “At certain range gates we were looking for their reactions and at each gate I was making decisions.”

The jets were Su-24 Fencers, air-to-surface bombers. When they got even closer, Armstrong read them another Safety of Flight Advisory, essentially warning them off. They didn’t respond.

As the Russian jets closed on Toronto, Armstrong was beneath the bridge in the ship’s darkened operations room, a place packed with radars, screens and notably, controls for Toronto’s weaponry.

One of Armstrong’s biggest decisions at this point was whether to turn on the ship’s fire control radar, which would enable the use of its sophisticated sea-to-air missiles. With the fire control radar off, the ship’s defences were lessened, but turning the radar on could be seen by the Russians as a prelude to firing.

On the bridge, Gillis had moved outside. The fighters appeared, a few hundred feet above the ocean and moving fast. As the first jet flew past, it pulled up and to the left, revealing to Toronto that it wasn’t carrying weapons.

“He came in very low on our bow,” said Gillis, “but then he rose and turned to show me the underside of his jet. He turned over and showed me that he had nothing; it was him saying, ‘I’m just having a look.’ That’s my interpretation.”

The jets just thundered past.

—–—–—–—–—–—–

In the March/April 2015 issue:

In part 2 HMCS Toronto continues its mission to deter the Russians on Operation Reassurance.

![]()

Advertisement