Under billowing clouds of an August day in northern France, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial looms over the ridge where Canadian soldiers carved the country its rightful place in the world. Its walls bear the names of 11,285 Canadian soldiers killed in France but whose remains were never identified. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

It is set on the ridge where all four Canadian divisions—100,000 troops—fought together for the first time, won a great victory, and thus staked their country’s place at the table and in the world.

Surrounded by battle-scarred field and forest where trenchworks and shell craters still disfigure the landscape and live ordnance renders much of it impassable, the memorial looms over the Douai Plains of northern France.

From its ramparts, one can see for dozens of kilometres in multiple directions—the very thing that made the ridge such a coveted piece of wartime real estate, first bringing the Kaiser’s troops to its lofty plateau in October 1914.

Company’s coming. Under the watchful eye of the Canada Bereft statue, alongside the names of Canadian dead whose remains were never identified, a maintenance man prepares the Canadian National Vimy Memorial for another day. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Between April 9 and 12, 1917, they finally attacked and secured the ridge after a costly four days of fighting. Of more than 10,000 Canadian casualties, 3,598 were killed in action.

Today, the towering memorial of magnificently crafted limestone, concrete and steel, with its multiple statues, can be seen from dozens of kilometres away, its walls bearing the names of 11,285 Canadians killed in France whose remains were never identified.

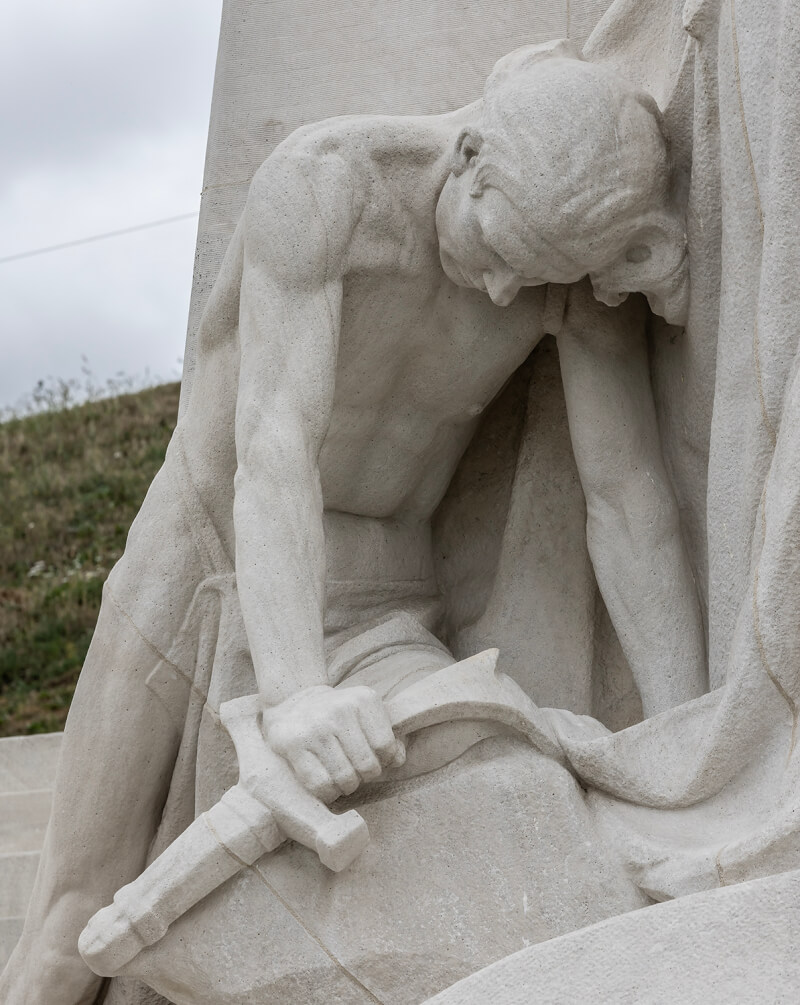

A soldier is depicted breaking a sword, representing the desired defeat of militarism

Created by Toronto designer and sculptor Walter Seymour Allward, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial is a monument to peace. One might even say, it is an anti-war memorial.

The towering figure of Canada Bereft mourning her lost sons overlooks the ridge where so many died and the plains beyond; a soldier is depicted breaking a sword, representing the desired defeat of militarism and reflecting the widespread desire for peace after four long years of slaughter.

Atop the ridge where soldiers fought, a couple make the tree-lined trek to the Vimy Memorial. It took designer Walter Seymour Allward 11 years to build before it was unveiled on July 26, 1936. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Two common chaffinches exchange greetings in the forest at Vimy Ridge.

Allward’s theme and design so enthralled Adolf Hitler that, when rumours spread that conquering Wehrmacht troops had damaged the four-year-old memorial, the German führer made a special detour en route to a defeated Paris in June 1940 to satisfy himself, and the world, that they hadn’t.

As a 20-something private in the WW I German army, Hitler never fought at Vimy, but he did see action in the area. He was wounded twice and evidence suggests that, despite his later brutality, Hitler was deeply marked by the experience.

The Canada Bereft statue gazes over the Douai Plains from atop the escarpment eight kilometres northeast of Arras. The seven-kilometre-long ridge rises 60 metres above the surrounding landscape, providing an unobstructed view for dozens of kilometres in all directions. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

They did their job. While many memorials in France were destroyed between 1940 and ’45, the cemetery atop Vimy Ridge as well as the memorial itself remained untouched, their status confirmed when Welsh Guards recaptured the hallowed ground in September 1944.

Today, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial stands as a monument to the country’s sacrifices in France and, for all intents and purposes, throughout Europe, during WW I. It is also an eloquently silent protest to the suffering, loss and futility of humankind’s greatest failures.

A monument points to Vimy and the ridge where Canadians did what those who went before could not. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Reconstructed trenchworks on the 700-metre-wide ridge give a sanitized perspective of life on the front line. The ridge fell under German control in October 1914. French forces took tremendous losses in trying to take it in 1915 before Canadians launched their successful attack at 5:30 a.m. on April 9, 1917. It was Easter Monday. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

More than 10 kilometres of tunnels were dug to support the Canadian Corps’ assault at Vimy Ridge. This included 13 large subways to move troops and supplies, protect communications and transport the wounded. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Nine Elms Military Cemetery in nearby Thelus, France, is filled with Canadians, most of them killed on the first day of the attack at Vimy Ridge, April 9, 1917. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Pte. John Roland Weir of the 10th Battalion lied about his age when he enlisted at Edmonton in December 1915. He was just 17 when he was killed at Vimy Ridge on the first day of the decisive battle, April 9, 1917. The aspiring young farmer is buried in nearby Nine Elms Military Cemetery. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Sculptors carved 20 double life-sized human figures on site from large blocks of stone. Breaking the sword is one of the more outspoken elements of what is an unapologetically antiwar memorial. While the Nazis destroyed many WW I statues and memorials in France and Belgium, Hitler personally visited Vimy en route to Paris in June 1940 and ordered the site to be placed under guard for the duration of the occupation. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Nicole Thomas of Legion national headquarters pins a poppy on colleague Lia Taha Cheng prior to a ceremony at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. The pair handled logistics for a 31-member RCL-sponsored pilgrimage with historian and guide John Goheen. It was Thomas’s last before she retired. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Legionnaires assemble for a remembrance ceremony at the base of the Vimy Memorial. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Legionnaires look on as veterans Roger Pineault of Quebec and Caleb MacDonald of Nova Scotia pin their poppies after laying a wreath at the Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Veterans Caleb MacDonald of Nova Scotia and David Scandrett of British Columbia walk the memorial with historian and guide John Goheen. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Terry Deslage of Quebec walks the Nine Elms Military Cemetery in Thelus, France, which was filled with Canadian dead after Vimy Ridge was taken in April 1917. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

When units collected their dead and couldn’t tell two of them apart, they buried them together. Here, 12 members of the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment) are buried in six plots at Nine Elms Military Cemetery. All were killed at Vimy Ridge on April 9, 1917. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Grave 7, Row E, Plot 8 in Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery near Vimy Ridge at Souchez, France : the last gravesite of an unidentified Canadian who was exhumed and interred in the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the National War Memorial in Ottawa in May 2000. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

The Canada Bereft statue watches over a young French girl picking clover at the base of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial. [Stephen J. Thorne/LM]

Advertisement