L’Anse aux Meadows, N.L., contains the excavated remains of an 11th century Viking settlement, the earliest evidence of Europeans in North America. [iStock]

“The Vikings (or Norse) were the first Europeans to cross the Atlantic.”

Vikings conclusively settled in Newfoundland nearly 500 years before Christopher Columbus reached the Bahamas, says new research that disproves once and for all the myth that the Italian explorer was the first European to discover the Americas.

By radiocarbon dating wood the explorers harvested at the L’Anse aux Meadows archaeological site in Newfoundland, scientists pinpointed the felling of trees to precisely 1021 AD, long before Columbus dropped anchor in the Caribbean in October 1492.

“The Vikings (or Norse) were the first Europeans to cross the Atlantic,” declares the peer-reviewed article in the scientific journal Nature.

The discovery “lays down a marker for European cognizance of the Americas, and represents the first known point at which humans encircled the globe,” it said. “It also provides a definitive tie point for future research into the initial consequences of transatlantic activity, such as the transference of knowledge, and the potential exchange of genetic information, biota and pathologies.”

It means pirate or raider.

The research led by archeologist Margot Kuitems from the Centre for Isotope Research at University of Groningen in the Netherlands acknowledges that the area around what is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site was occupied by Indigenous Peoples long before the 100 or so women and men arrived from Greenland.

But they did not have the metal tools the Vikings had used to cut the trees. This was a key aspect of the new research.

‘Viking’ is generally believed to be the name given to Norse raiders by the English they raped and pillaged between 750 and 1100 AD. It means pirate or raider.

It is derived from the Norse víkingr or víking, meaning someone who “went on expeditions, usually abroad, usually by sea, and usually in a group with other víkingar (the plural),” wrote Judith Jesch, a professor of Viking studies at England’s University of Nottingham, in a 2017 essay. The more pejorative meaning evolved.

Previous research at the site at the north tip of Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula suggest it was a base camp from which other locations, including regions farther south, were explored.

That finding—that Vikings wandered beyond Newfoundland—was made in 2009 by Parks Canada archeologist Birgitta Wallace, a co-author of the new paper, and may explain why plant species native to the island and some European-type artifacts from the period have been found in the northeastern United States.

Previous estimates of the settlement’s date were based on the style of L’Anse aux Meadows’ architectural remains, a handful of artifacts and interpretations of Icelandic sagas—oral histories inscribed on vellum (calf skin) in the 13th century.The new research, whose authors include Parks Canada and Memorial University of Newfoundland scientists, was based on the latest technologies and techniques, including “high-precision accelerator mass spectrometry,” a highly technical form of dating objects—in this case, tree rings.

The scientists were able to align certain rings with known cosmic radiation events, likely massive solar flares, in 775 and 993 AD. They’re called C dates, and they are identifiable worldwide by a naturally radioactive form of carbon found in organic materials such as wood, bone and charcoal.

At L’Anse aux Meadows, the telltale carbon-14, which trees inhaled from the atmosphere, was found in ancient pieces of wood—some sticks, part of a tree trunk and what appears to be a piece of planking.

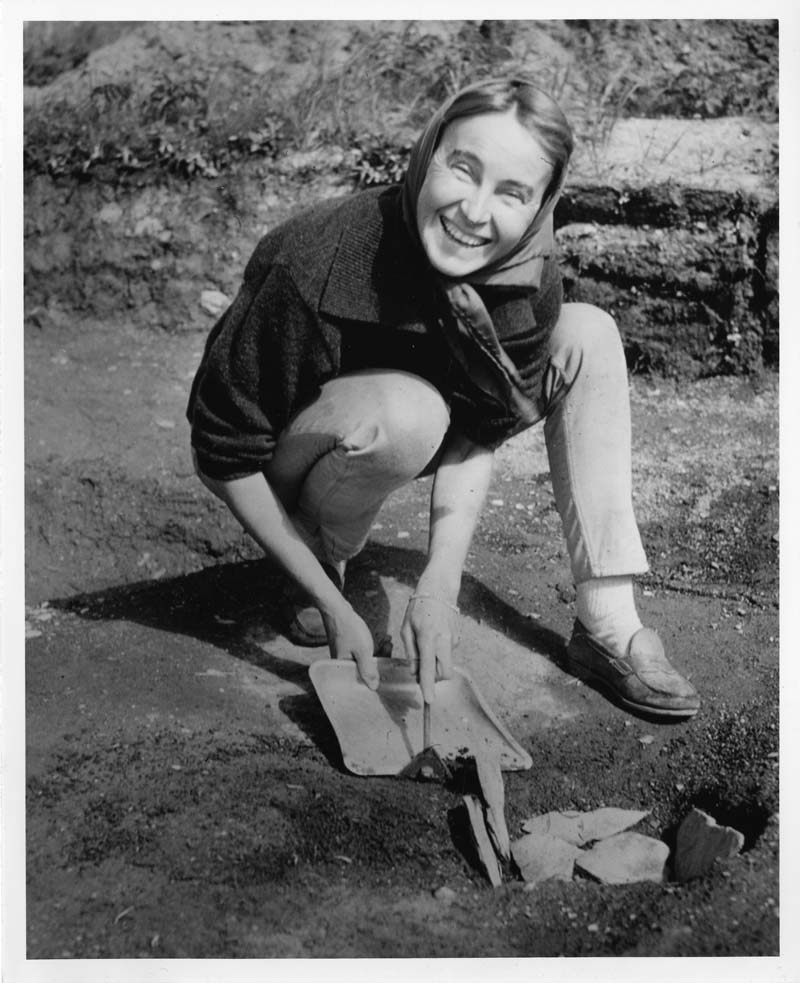

A 1963 photo of Norwegian archeologist Anne Ingstad, who discovered L’Anse aux Meadows with her husband, Helge, in 1960. [Wikimedia]

“Once the ring that contains the AD 993 anomaly has been detected, it simply becomes a matter of counting the number of rings to the waney edge. On the basis of the state of development of the earlywood and latewood cells in the waney edge, one can even determine the precise felling season.”

The team sampled 83 individual rings from the items, which came from two fir trees and one juniper. All the wood samples had been modified by metal tools unavailable to the area’s Indigenous inhabitants at the time.

The findings were consistent: all of the trees were felled in 1021 AD, one in the summer, one in the fall, and the other undetermined.

The Norse are believed to have occupied L’Anse aux Meadows for between three and 13 years.

“Our result of AD 1021 for the cutting year constitutes the only secure calendar date for the presence of Europeans across the Atlantic before the voyages of Columbus,” says the paper.

“Moreover, the fact that our results, on three different trees, converge on the same year is notable and unexpected.”

The Norse are believed to have occupied L’Anse aux Meadows for between three and 13 years before they abandoned it and returned to Greenland.

Two Icelandic sagas suggest the explorers had arrived in up to six expeditions, the first led by Leif Erikson, known as Leif the Lucky, son of Erik the Red, who is said to have founded the first Norse settlement in Greenland.

The sagas refer to the region as Vinland, Old Norse for “land of wine.” Any thoughts of growing grapes in Newfoundland were soon abandoned, however, and it is believed the Norse explored warmer areas to the south for the purpose.The sagas indicate the Newfoundland site was ultimately abandoned due to infighting and conflicts with Indigenous Peoples, whom the Norse called skræling, believed to mean “wearers of animal skins.”

The paper says if such encounters between peoples did occur, they may have had “inadvertent outcomes, such as pathogen transmission, the introduction of foreign flora and fauna species, or even the exchange of human genetic information.”

Recent data from the Norse Greenlandic population, however, show no evidence of the latter.

“It is a matter for future research how the year AD 1021 relates to overall transatlantic activity by the Norse. Nonetheless, our findings provide a chronological anchor for further investigations into the consequences of their westernmost expansion.”

Advertisement