Illustration by Robert Carter

How many veterans kill themselves?

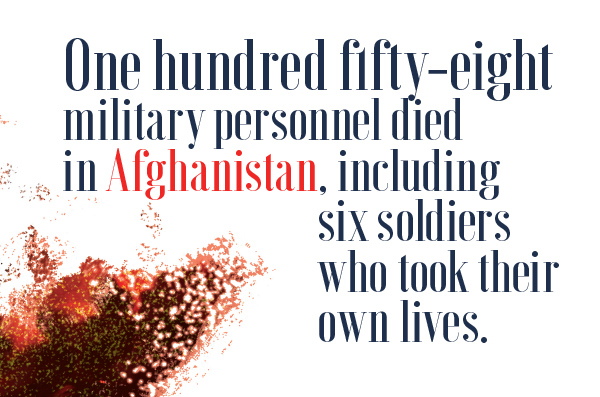

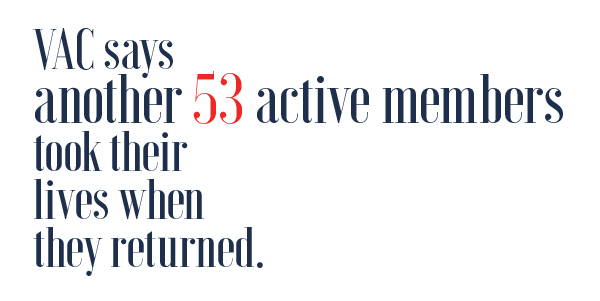

The answer is: We don’t know. Do military suicides outnumber combat deaths? The Department of National Defence says six soldiers took their lives in Afghanistan. Veterans Affairs Canada says 53 active members took their lives when they returned. Citing Department of Defence figures, the Toronto Star reported that 160 personnel committed suicide between 2004 and 2014. We do know CAF combat deaths in Afghanistan totalled 158. In the U.S., the number of soldiers who died in Iraq and Afghanistan was 5,866; the number who took their own lives was 6,256. The rate of military suicide in the U.S. is double the rate in the civilian population.

The CAF released a report in 2015 that said the suicide rate for active members was roughly the same as the general population. Though their study didn’t include reservists, who made up more than a quarter of the force in Afghanistan, and didn’t include those who had already left the forces. Of the 40,000 who served in Afghanistan, roughly half were reflected in the study.

The study was criticized as a PR tool (high-risk personnel are discharged for medical reasons and weren’t part of the study), and sociologists argued that comparing the CAF rate to the general population was misleading, given that young, fit recruits are being compared to high-risk civilian groups.

Dr. Elizabeth Rolland-Harris, who conducted the study, agrees that it is “imperfect” though says there needs to be some kind of yardstick, and the general population is what the public can best relate to.

(A new report released by the Surgeon General in November found no significant increase in the overall suicide rates of regular forces males between 1995 and 2015.)

The only other military suicide statistics we have come from the Canadian Forces Cancer and Mortality study, which looked at suicides for those who enlisted between Jan. 1, 1972, and Dec. 31, 2006, excluding reservists. When all ages are considered, the risk of suicide was not significantly different for serving members than the general population. However, among released male members, the risk was about one and one half times higher.

There are no numbers for veterans alone, but Veterans Affairs Canada and Statistics Canada are currently working to isolate veteran suicides and will have data by December 2017. What we may find is that veterans are among the most vulnerable groups in the country. When it comes to suicidal traits flagged by researchers, military veterans present a perfect storm.

Thomas Joiner, a psychologist at Florida State University and one of the world’s leading suicidologists, has a theory for vulnerability that outlines three distinct traits. The first is “thwarted belongingness”—the individual feels alienated, is unable to connect socially and/or emotionally. The second is “perceived burdensomeness,” the idea that family and friends, or perhaps the entire world, would be better off without them. These are preconditions, but as Joiner points out, millions of people feel this way and don’t kill themselves. The reason, he argues, is that they don’t possess the third, and crucial trait—“acquired fearlessness.” They are unable to overcome their fear of death and their natural instinct for survival.

This last prerequisite is one of the reasons that military personnel (and police) tend to be more successful when attempting suicide. They have greater familiarity with violence, weapons and death than most civilians.

Some veterans are candidates for all three of these risk factors. Steve Rose, a sociologist who studies military suicide, noted that roughly one third of those who leave the CAF have difficulty making the transition to civilian life. Every year 4,500 personnel leave, 1,700 of them by “forced release,” meaning they are no longer fit and able.

“When veterans leave military service,” one veteran wrote on Rose’s blog, “many of them, like me, are leaving the most cohesive and helpful social network they’ve ever experienced. And that hurts. Most recent veterans aren’t suffering because they remember what was bad. They’re suffering because they miss what was good.”

What happens to soldiers when they attempt to re-enter society can be jarring. Seventy per cent of U.S. soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan were subsequently divorced, exacerbating their sense of not being connected. A U.S. Senate report estimated that 1.4 million veterans live below the poverty line. In Canada, an estimated 2,250 veterans are homeless. Those with disabilities, or who can’t find work, might experience a sense of “perceived burdensomeness.”

And there is no better place to acquire fearlessness than the military.

Armed forces need to instill a sense of fearlessness in soldiers. Without it, the army can’t be effective. The difficulty is creating an environment where the warrior can also seek help for PTSD or suicidal thoughts.

How to reconcile these? “They’re going to have to reconcile it,” said Antoon Leenaars, suicidologist based in Windsor, Ont., and author of Suicide Among the Armed Forces: Understanding the Cost of Service. “Because it’s increasingly normal to suffer PTSD in battle. We will be judged on how we protect those people who protect us.”

Bruce Moncur is president of the Afghanistan Veterans Association of Canada, a Windsor-born, Texas-raised veteran who was injured in Afghanistan, part of his skull blown out by friendly fire. Five per cent of his brain was removed. He was originally awarded $22,000 and an additional settlement which remains confidential. Moncur also received $134,000 for PTSD.

Moncur is bitter about his experience in the military and feels it has let him and other veterans down. He argues that military culture, for all the stated intentions about providing help for mental health issues, remains hawkish and judgmental. “You have colonels who want to be seen as John Wayne (who avoided serving in the Second World War),” he said. “They don’t want to appear to be wishy-washy on suicide. It’s a cancer they don’t want to spread. It’s a big green machine. If a cog doesn’t work, you get another one.” And the broken cog is mustered out, away from active members, and beyond the statistical reach of the CAF.

VAC points to the systems that are in place to help; veterans speak about paperwork and bureaucracy and the need for more education. Barry Westholm, former sergeant-major for the Joint Personnel Support Unit, said that one way to mitigate suicide is to educate recruits on what VAC provides when they enlist, as opposed to having them navigate that system with a debilitating injury.

Not all military suicides were the result of deployment—31 per cent of U.S. military suicides weren’t deployed in a combat zone, and Canadian statistics show a similar pattern. But the numbers suggest a causal link between combat and suicide. In the U.S. there is fear that the alarming rise in suicide rates after Iraq and Afghanistan (more than doubling between 2001 and 2006) has become the new normal. It was hoped that this was simply a spike, but the rates haven’t gone down in the decade since, and remain roughly twice the civilian rate. In the American Civil War (1861-65), one of the first to provide data on suicide, the suicide rate was highest in the year after the fighting ended. It can take a while to manifest itself.

The 2015 CAF suicide report statistics indicate higher suicide risk in the last decade among those who have deployed.

“We haven’t seen the worst of this,” said Leenaars. “That will come in five to seven years. This builds up—alcohol, drugs, divorce, isolation. We could see a big increase in suicide.”

Perhaps it is no coincidence that the modern study of suicidology began in a veterans’ hospital. In 1949, Edwin Shneidman, a young clinical psychologist working in a VA hospital in Los Angeles, was given the job of writing condolence letters to the widows of two soldiers who had killed themselves. Shneidman went to the coroner’s office and found that one had left a suicide note. While there, he found hundreds of suicide notes. Shneidman took the notes (without permission) and analyzed them, the start of a lengthy career devoted to suicide. He is considered the father of modern suicidology.

Over the decades, others have built on Shneidman’s work. One of the obstacles has been available data. Suicide statistics have been notoriously unreliable, though there is general consensus that they are under-reported. Coroners determine cause of death, and they can’t always discern between accidental death and suicide. A 2006 study stated that up to five per cent of single-vehicle accidents were suicides.

In the U.S., the National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) was created to provide meaningful data on suicide and homicides. The database provides age, means, information from medical examiners and law enforcement, and coroners’ reports. It can also cite mental health issues, relationship status and employment records. It is a boon for sociologists studying the issue.

At the VAC stakeholders meeting in October, suicide data was one of the issues that came up. Aaron Bedard, an Afghanistan veteran, complained about the issue. “We’ve been pushing for a year and a half for suicide data,” he told The Globe and Mail. “We want to know where, when and why people commit suicide after they serve and how soon after they have left the military.”

Where and when are achievable but the why is more elusive. Suicide is a multi-disciplinary subject that incorporates social, biological, cultural and psychological factors. David Lester, a suicidologist who recently retired from teaching at Stockton University in New Jersey, spent his life studying suicide and its causes, writing dozens of books on the subject. At a suicide conference in Niagara Falls several years ago, he spoke about the difficulties in determining a cause. “What have we learned?” he asked rhetorically. “I have no conclusion, no tidy ending. Perhaps nothing special happens, but one more grain of sand added to the pile results in the pile collapsing, and then we hold that grain of sand responsible for the collapse.”

We don’t know if it was the divorce, the abuse he/she suffered as a child, the trauma suffered as an adult, the isolation, the inability to find a job, the depression.

Globally, more than one million people commit suicide each year, more than die in battle. It is a growing problem that still carries a stigma, both in civilian and military life. No group is immune but certain groups are more vulnerable—aboriginal youth, for example. Some risk factors aren’t necessarily surprising—divorced people have a higher rate, as do the childless, and those without a college degree. But some high-risk groups are a surprise: doctors and dentists have higher rates, as do middle-aged male lawyers. It will be a surprise if the data doesn’t indicate that veterans are at higher risk for suicide.

Minister of Veterans Affairs Kent Hehr “is committed to paying tribute to all those who served, including those who have fallen.” What isn’t clear at this point is who the fallen are. One hundred fifty-eight military personnel died in Afghanistan, including six soldiers who took their own lives. VAC says another 53 active members took their lives when they returned.

There is currently a ministerial advisory group tasked with the job of determining how best to remember all the fallen, including those who took their own lives. They are faced with the unanswerable question: Are military suicides casualties of war?

Rather than try to answer it, we need to recognize their sacrifice and commemorate them. The new data will help identify trends and the scale of the problem. But there is a need to reconcile a warrior culture with mental illness and suicide, which have been uneasy bedmates for millennia. VAC has mechanisms in place to help those in need but the bureaucracy can be lumbering and daunting to someone with PTSD. And military culture is a stubborn thing. We need to look past the heroic John Wayne screen persona and accept the realities of war.

Advertisement