Megan Thompson of Defence Research and Development Canada. [Sharon Adams]

A 19-year-old Canadian soldier serving in a village halfway around the world is in a unit tasked with securing an area and protecting civilians within in an effort to build civilian support and goodwill.

Suddenly a pregnant, robed woman, gesturing wildly, races toward him shouting words he cannot understand. Is she in need of help…or is that bump a bomb, not a baby? What should he do? He has mere seconds to decide.

Perhaps she is an innocent civilian. But if she is a suicide bomber and he does nothing, soldiers and civilians will die. If he shoots or injures her and she was genuinely in need of help, the community will turn against the military. No matter what he decides, he may sustain a moral injury and be haunted by guilt and shame.

Military personnel at all levels are confronted by moral and ethical dilemmas that have no quick and easy solution, but have huge consequences, both to their mission and to their mental health, military mental-health experts heard at a NATO lecture series examining moral injury, hosted by The Royal Ottawa Mental Health Centre in November.

“A single bad decision can erode local, national, international and host nation support, thereby derailing the strategic mission and putting troops at risk,” said Colonel Eric Vermetten, head of military mental-health research for the Dutch Ministry of Defence.

Yet the military has historically provided “little guidance to those facing stark choices in the heat of conflict,” said Megan Thompson of Defence Research and Development Canada in Toronto, a proponent of merging scenario-based, operational-ethics training into high-intensity combat and mission training.

Ethical decision-making is a skill like any other, she argues, and improves with rehearsal.

Moral injury occurs when an action (or lack of action) violates deeply held moral beliefs about such things as fairness, the value of life or honour. “It’s a betrayal of what’s right,” said Vermetten.

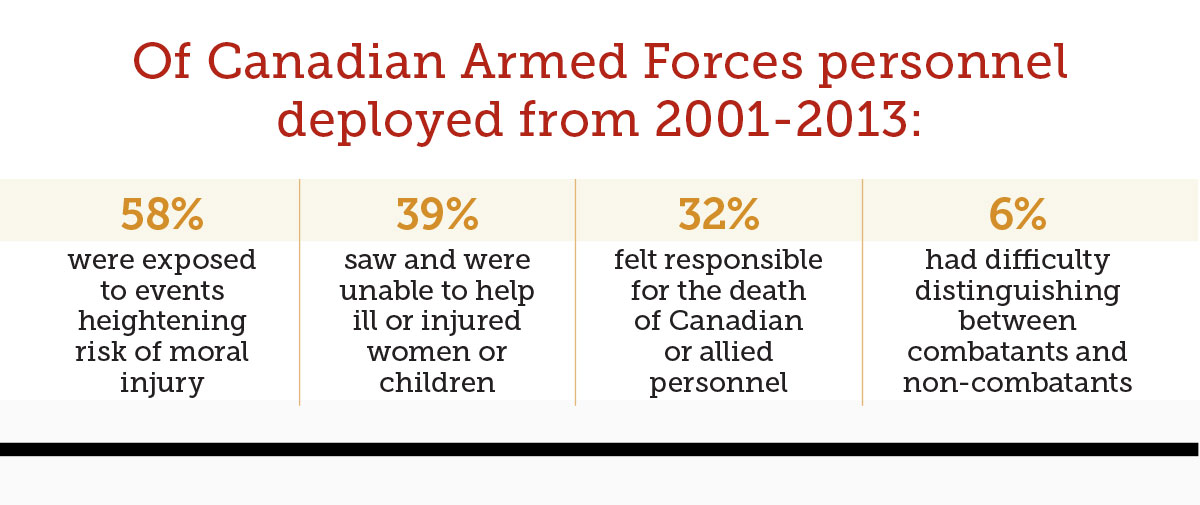

Causes include witnessing or participating in atrocities (such as murdering a surrendering or wounded enemy), unintentionally causing the death of a civilian or comrade, or being unable to act due to orders (not intervening to prevent a massacre or rape, orders not to share rations with starving children), or feeling betrayed (an officer behaves unethically). Symptoms can include shame and guilt, anxiety and anger, alienation and withdrawal, sleeplessness and self-harm.

While it is not possible for training to address every situation troops may encounter, troops and leaders can learn to recognize situations calling for an ethical or moral decision and to understand implications of the event. They need to recognize that there are difficult and sometimes competing moral issues to identify their moral responsibility and to learn a method to help them make the decision.

There is a link between ethical and moral decisions and troops’ mental health—“a crucial component of leaders’ responsibility for their soldiers,” said Col. Christopher Warner, commander of United States Army Medical Department Activity—Fort Stewart.

Various studies of U.S. troops at various times found less than half believe civilians should be treated with dignity and respect, a third believe torture was allowable to gain intelligence, a third had insulted non-combatants, more than 10 per cent had damaged civilian property, and five per cent had hit or kicked civilians. “There was a call in the U.S. military to do something,” said Warner.

U.S. research has shown a link between unethical behaviour and development of mental health conditions, he said, and that training in ethics does reduce the incidence of moral and ethical infractions—thus preventing or limiting moral injury.

Leadership is the key to maintaining ethics on the battlefield, said Warner. It begins with education and training, but has to be followed up during deployment by engaged leaders who discuss with their troops moral and ethical situations as they arise. They need to watch for changes in behaviour that might indicate moral injury, and follow up when troops return home.

The search is on for the best approach to treating moral injury. It became clear that evidence-based treatments for PTSD do not address symptoms of moral injury, said Col. Rakesh Jetly, senior psychiatrist with the Canadian Armed Forces mental-health directorate. That raised a number of questions about moral injury still under debate. Is it one of the many symptoms of PTSD—or a separate injury altogether? Does it fall under the bailiwick of doctors, or lawyers, or chaplains, or commanding officers? Or do they all have a role to play?

The international NATO lecture series seeks answers to these questions. The Ottawa session was attended by military mental-health experts from Canada, the Netherlands, the United States and Britain, as well as the Canadian Institute for Military and Veteran Health Research. They will make recommendations for educational and ethical training programs and support to be used before, during and after deployment and share information on such topics as diagnosis and the best treatment for moral injuries.

Advertisement