The Canadian National Vimy Memorial was the last stop of the 2023 Royal Canadian Legion Pilgrimage of Remembrance.[Aaron Kylie/LM]

Now it feels personal. Whether you’re in the medieval courtyard of Abbaye d’Ardenne in France, where the Nazis brutally executed 18 Canadian prisoners of war less than 48 hours after D-Day; or you’re standing on an unmarked dirt track in a wheat field just east of a tiny French hamlet where Lieutenant Reginald Barker died valiantly saving five of his Canadian comrades from being ruthlessly gunned down by SS troops around the same time; or you’re at the Adegem Canadian War Cemetery in Belgium standing over the grave of Sergeant William S. Hawthorne, who died on Sept. 9, 1944, at the age of 26, honouring the epitaph on his marker: “His grave we may never see but may some kind friend say a prayer at this sacred spot for me;” when you stand on these hallowed grounds, you gain a new appreciation of the weight of war—and remembrance.

Some two dozen Canadians, including select rank-and-file members of The Royal Canadian Legion, provincial RCL representatives, a trio of Legion headquarters’ staff, and guests, participated in the organization’s biennial Pilgrimage of Remembrance in July 2023. The 14-day tour of First and Second World War sites in France and Belgium focused exclusively on Canadian battlefields, cemeteries and memorials and unmarked rural roadside battle sites—where few, if any, other such excursions stop.

“It’s John’s middle-of-nowhere tours,” said John Goheen, the pilgrimage’s voraciously knowledgeable guide-cum-narrator. (Or, as one pilgrim put it: “I’m beginning to realize that every field tells a story.”) An avid military historian and former school principal from Port Coquitlam, B.C., Goheen is an expert storyteller, bringing life—and equally evocative death—to staid granite monuments and quiet abandoned hillsides alike.

The pilgrimage was, of course, much more than history lessons. A camaraderie developed among attendees (what would a day be without another joke from Padre Paul?); friendships were made and rekindled (Louison earned the nickname Google); fun and frivolity reined on bus rides (particularly with faa-thur at the back of the bus); bus drivers were loved (yeah Jaco!) or loathed (unnamed for his protection); refreshments were imbibed and solemn formal ceremonies were held.

Pilgrims pose for a group photo at the St. Julien Canadian Memorial in Belgium.[Aaron Kylie/LM]

Still, among the jam-packed days, what stood out were the stories of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. And while a story of the tour could be told in dozens of different ways, guide Goheen involved participants in a particularly memorable part of the pilgrimage: relate the story of a First World War soldier at his gravesite. Each pilgrim’s recounting was compelling, but three in particular, when combined, manifest an intriguing snapshot of Canada’s role in WW I.

Just steps from famed John McCrae’s plot in the Wimereux Communal Cemetery in the small French town on the Strait of Dover, lies the far-less-famous Sergeant Robert Parker of Victoria.

Parker’s tombstone, like all those in the Wimereux burial ground, lies flat. The sandy soil is too unstable for upright markers. Nearly 110 years after Parker’s death, pilgrim Ken Pendergast, an executive member of B.C.’s Prince George Legion Branch, is standing over Parker’s final resting place.

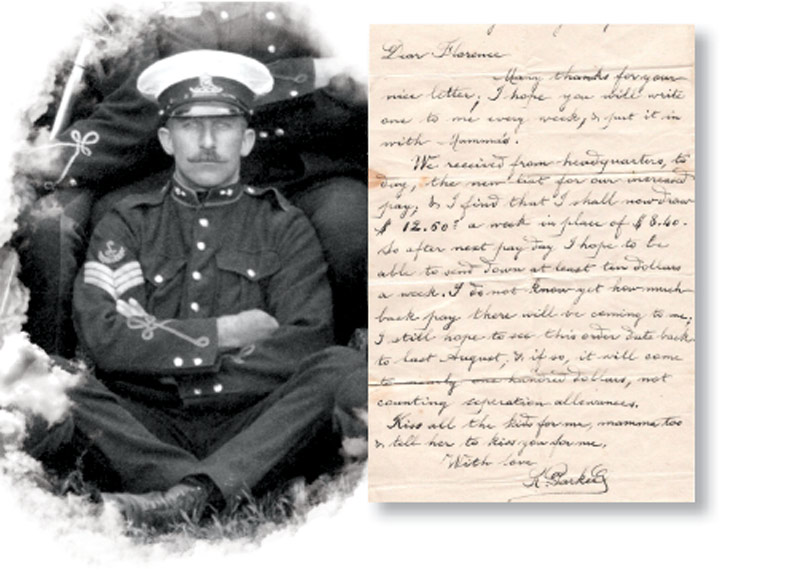

Sergeant Robert Parker of Victoria died on May 31, 1915, from wounds suffered during the Battle of Festubert. In a letter home just months earlier he wished “that the war come to a speedy end.” [Courtesy Ken Pendergast;]

Pendergast, now 79, joined the Royal Canadian Air Force at 17. After a few years of service, he ended up in Prince George, eventually building a career as a top provincial forestry bureaucrat, then consultant. He retired in 2007, though in addition to his work with the Legion, he’s a consummate helping hand with numerous other community organizations. Word is, if you need a local volunteer to make it happen, you call Pendergast.

Mid-July 2023, Pendergast has the rapt attention of his fellow pilgrims as he shares details of Parker’s life and service.

Heeding the country’s call to arms, the five-foot, five-inch carpenter enlisted on Sept. 22, 1914, four months shy of his 39th birthday. Despite a reluctance to take older men with families—he was married with seven children, his youngest just five months, his eldest 14—Parker had militia experience, having served for 12 years in the 5th Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery. He was also born in Caen, France, though he grew up as part of the city’s wealthy English population, so there was likely strong dual patriotic duty at play.

As a teenager, he and his older brother, Herbert, immigrated to Canada, settling on a farm near the Qu’Appelle River valley east of Regina. After marrying, he moved to Victoria with most of his in-law’s family in 1901.

“The war came, and he had to go,” his last surviving child, Gladys George, told an interviewer in 2005. She was two years old when her father sailed with the first Canadian contingent overseas in late September 1914. She would never see him again.

The following spring, Parker was assigned to the 7th Battalion (1st British Columbia). He joined shortly after the 7th had fought in Canada’s first major action in the Great War during the Second Battle of Ypres. Its men had watched as the Germans unleashed the first-ever gas attack on April 22. Then days later, as it fought to hold the line northeast of Saint Julien, the battalion had been decimated. Just about a third of its troops answered roll call on April 25. Parker was among a group of reinforcements for the 7th that arrived at the front on May 7.

The 7th was soon back in action at the Battle of Festubert, considered the second major engagement fought by Canadian troops during the war. The First Canadian Division joined a wider British attack on the German front line near the French village on May 18. The offensive’s costliest day for the Allies was six days later.

Parker’s 7th suffered among them on May 24. The battalion’s commanding officer, Major Victor Odlum, wrote in the unit’s war diary that, at 4:30 p.m., “shelling has been heavy during last hour and casualties are again very numerous.” Less than three hours later he noted that the “entire reserve company will be put to evacuating wounded as soon as it is dark. We are collecting all stretchers to be found in neighbourhood.” The 7th sustained nearly 200 killed and wounded that day.

Parker was among the casualties, machine-gun bullets having ripped into his chest and thighs during the fighting. He survived, however, and was taken to a dressing station near the battlefield, then transported via train to Wimereux, 100 kilometres away, to the Rawalpindi British General Hospital. There wounded soldiers were stabilized so they could be sent back to England for further treatment.

But Parker didn’t make it. He died of his wounds a week after he was hit, May 31. He was buried the following day. Just months earlier he had written home: “God only knows what is in store for me. May He grant, for all your sakes, that the war may come to a speedy end.”

Parker’s war lasted just nine months. For the world, it would continue for another 53.

Private Russell Bernard Tobin rests in the Passchendaele New British Cemetery, likely about two kilometres from where he fell on Oct. 30, 1917. Fighting with the 85th Battalion (Nova Scotia Highlanders), Tobin was one of more than 4,000 Canadians killed in the Allied offensive that ultimately claimed the ruined Belgian village on the Western Front.

The Canadian Corps joined the battle on Oct. 26 and, despite attacking on a muddy, open battlefield under heavy enemy fire, it reached the outskirts of Passchendaele by the end of a second push during a driving rainstorm on the day Tobin died.

But in mid-July 2023, a bright blue sky greeted pilgrims visiting his gravesite. Captain Madonna Jackson, a Legion member from Dr. C.B. Lumsden Branch in Wolfville, N.S., readied to relay his story to her fellow Legionnaires. Jackson, 57, is a cadet instructor cadre officer with the 106 Royal Canadian Air Cadet Squadron, having served nearly 20 years in the reserves as part of the training program.

In a creative turn, Jackson took on Tobin’s persona, sharing elements of his life and service with her fellow pilgrims as if she were him. “This girl you sent to give me my voice did some digging for me,” began Jackson.

Tobin was born on May 23, 1890, on Sable Island, a 35-kilometre long, 1.6-kilometre wide, sandspit some 300 kilometres south of Halifax, famed today for its wild horse population. The island’s earliest inhabitants were families of life-saving crews and lighthouse keepers. Reportedly only two people have been born on Sable since 1920.

Tobin’s family later moved to Woodlawn, N.S., then a rural farming community, today a suburban area of Dartmouth. Tobin listed his occupation as farmer when he enlisted, just before his 26th birthday, on Mar. 22, 1916. He was single, five-foot-7.5-inches tall, 167 pounds, with blue eyes, dark hair and a fair complexion. He sailed overseas eight months later aboard RMS Olympic, Titanic’s sister ship. A year later, Tobin was fighting at Passchendaele, amid what some historians call the worst horrors of the Great War.

The tombstone of Private Russell Bernard Tobin in the New British Passchendaele Cemetery. Pilgrims Anastasia Dufour (left) and Madonna Jackson salute during a cemetery service. [Times Colonist files; Aaron Kylie/LM (2)

“During the morning of 29/10/17 Major [Percival] Anderson on reconnoitring his front line, discovered that the Hun was in strength about thirty yards on the right flank and about one hundred and fifty yards away on the left flank,” noted the war diary of Tobin’s 85th.

The Canadians launched a barrage at the Germans as the 85th temporarily fell back. In the afternoon, “a considerable amount of sniping and Machine Gun fire played about the area” reported the diary. Shortly after dusk, all was set for the next day’s push involving ‘A,’ ‘B’ and ‘C’ companies.

They were in position at 4:50 a.m. Tobin’s ‘A’ was on the left.

“At Zero hour [5:50] the first sound heard was the Brigade machine guns,” noted the diary. “On this, all Companies pushed forward. They were met by heavy machine-gun and rifle fire.” Two company commanders were killed instantly.

Still, they advanced passed their old front lines, “then in No Man’s Land a fierce fight took place,” wrote the diarist. “The line was drawn closer and closer to the enemy…men jumping from shell-hole to shell-hole, but anyone who attempted to walk upright instantly became a casualty.”

Pilgrim Gayle Mueller poses for a photo by the grave of Private Stephen Arsenault, who died some six weeks before the end of the war.[Aaron Kylie/LM ]

The diary noted there were several instances of this, including by Tobin’s comrade, Sergeant Oscar Rushton, “who sprang to his feet, waved his arms over his head, shouted ‘Come on, ‘A’ Company,’ made direct for the nest of machine-guns in front—and fell dead.”

The firefight lasted 10-30 minutes. The objective captured just 50 minutes after the push had begun. But the 85th suffered heavily, nearly 400 killed and wounded of some 700.

Tobin was reported wounded and missing that day, but later confirmed killed in action. There are no exact details of his demise, though one wonders if he fearlessly followed Rushton, popping from a shell hole in a daring stab at silencing the Germans guns.

“Long time since I had a wet,” said Jackson still channelling Tobin as she concluded her story by proposing a toast. “She and I were going to have one together. But then she thought, there’s that guy that keeps trying to preserve this history,” Jackson continued, referring to pilgrimage guide Goheen. “He keeps telling our story and bringing people here to give us our voice. And maybe I’d like him to have a wet, too.

“This girlie promises to always tell the story. Cheers.”

Private Stephen Arsenault lies in the Bucquoy Road Cemetery just south of Arras, France, due west of the autumn 1918 war front. The Hundred Days Offensive, the Allied push that would lead to the conflict’s conclusion, was near its midpoint when Arsenault died on Sept. 28, 1918.

Pilgrim Gayle Mueller stood behind Arsenault’s tombstone on a sunny mid-July 2023 day, poised to deliver details of his life and service.

Mueller is vice-president of the Legion branch in Summerside, P.E.I., which is named in honour of Great War veteran George Pearkes, recipient of the Victoria Cross for his actions at Passchendaele. Mueller, now 75, served herself, joining the family business, if you will, with 17 immediate relatives in the military. She enlisted with the RCAF in July 1967, working as a “crypto girl,” coding, decoding and transmitting messages for five years, before being forced out to raise a family.

Mueller began her telling of Arsenault’s story by relating her early struggle to translate his service file into a biography: “Just the bare necessities were there.”

He was born in Abrams Village (now Abram-Village), P.E.I., just west of Summerside, on April 2, 1893. He was a single, five-foot-three-inch tall, 146-pound, 24-year-old labourer residing in Lawrence, Mass., when he enlisted in January 1918. He sailed for England in early March and arrived at the front mid-month, assigned to the 5th Battalion (Saskatoon Light Infantry).

But Mueller wanted more. She started making calls and visited the Legion branch closest to Abram-Village in Wellington. She heard a common response to her queries: “You’ve got to talk to Earl Arsenault.”

The Arsenault family historian helped Mueller paint a picture of the early life and family of her “solider boy.”

“You don’t need to worry, girlie,” Earl told Mueller. “I’ve got it all.”

The family had 14 children, eight boys, six girls, living in a small farmstead in the tiny rural community of farmers and fishermen. Music was important: dad played the fiddle, mom the piano, and the home was regularly brimming with song and dance. They were hardworking and readily helped neighbours in need.

“Stephen,” Earl told Mueller, “learned about hard work and sacrifice at a very young age.”

Stephen Arsenault’s greatest sacrifice came amid the late September 1918 Battle of the Canal du Nord. Historians say it was among the most costly but impressive engagements fought by the Canadian Corps during WW I.

The 95-kilometre-long, 35-metre-wide Nord waterway runs north-south in northern France just west of Cambrai. It connects two other canals. Construction began in 1908, but stopped when the war began. In the fall of 1918, the Allies were on the west side continuing to push the Germans east. While the canal was dry, its banks were several metres high, and the enemy had flooded the adjacent area. Plus, the Canadians assigned to cross it didn’t know for sure what was waiting on the other side.

On Sept. 27 at around 5:30 a.m., the Canadians launched a creeping barrage with four battalions, Arsenault’s 5th among them, to bridge it.

“Heavy rain fell during the night, which, although materially assisting the movement of the men into Assembly positions, was most uncomfortable for them,” reported the 5th’s war diarist. Still, “everyone was in a boisterous spirit, eager and anxious to take part in the great fight.”

The canal was crossed at 11 a.m. and the day’s objective was reached by 2 p.m. The following day, the Canadians continued their move, clearing the sector’s trenches and the villages of Raillencourt and Sailly in heavy fighting. They were stopped, though, by heavy German shelling. Arsenault was cut down during the day’s action, sustaining a shrapnel wound to his right thigh, his hip and his left leg. He died of his wounds. His battalion was relieved the following day. Arsenault was one of 23 5th men killed and 220 total casualties in the four days.

The battle concluded on Oct. 1. The Canadian Corps at large suffered more than 10,000 casualties. The losses, however, contributed greatly to the liberation of Cambrai a few days later and the continued advance to end the war.

“Stephen had no wife and children to keep his memory alive in their hearts. “So, I will become…” said Mueller, putting her hand to her heart, her voice trembling momentarily with emotion, “I will become that family.”

The Vimy Memorial has drawn war-site pilgrims since its unveiling in 1936.[Aaron Kylie/LM ]

Howdy, pilgrim

The Legion first hosted a war-site pilgrimage to France in 1936 for the unveiling of the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, the iconic tribute to all Canadians who served in WW I and that bears the names of 11,285 of its sons who died in France with no known grave. Some 6,500 veterans and their family members made the trip on five ships.

A second Legion pilgrimage to the Netherlands occurred in 1962, though with a much smaller contingent of 79. Seventeen such trips followed during the next decade, with Dutch families hosting more than 2,000 Canadian visitors over the years.

In 1986, 10 younger Legionnaires, one from each province, returned to Vimy for the 50th anniversary of the memorial’s unveiling. After a three-year gap, the program resurfaced as the Legion’s Youth Leaders’ Pilgrimage of Remembrance. It continued annually until 1997.

In 2013, the initiative took on its current form, in which one Legion member from each of the organization’s 10 territories is selected to participate—and subsequently share their experiences with their families, friends and communities at large.

Advertisement