Cologne Cathedral stands tall at war’s end, surrounded by devastation wrought by the Allied bombing campaign.[Wikimedia]

The finale of a Second World War television trilogy has arrived on Apple TV+ and early episodes of the graphic and visually stunning Masters of the Air have already made some questionable claims about the U.S. bombing campaign over Nazi-occupied Europe.

Produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks, the nine-part series comes 26 years after Saving Private Ryan (1998) hit theatres and set the standard for HBO TV’s subsequent series, Band of Brothers (2001) and The Pacific (2010).

Their realism, casting, cinematography and attention to detail changed the trajectory of wartime moviemaking. Masters of the Air follows that formula with a compelling story, visually stunning scenes and, by most accounts, deadeye detail.

Based on the voluminous book by historian Donald L. Miller and scripted by John Orloff, it tells the tale of the American daylight bombing campaign through the experiences of two members of the U.S. Eighth Force’s 100th Bomb Group, majors John (Bucky) Egan (Callum Turner) and Gale (Buck) Cleven (Austin Butler).

Austin Butler plays Major Gale (Buck) Cleven in Masters of the Air on Apple TV+.

[Apple TV+]

That claim isn’t true. The atomic bomb may have been the most closely held secret of WW II, but codebreaking in Poland and later at London’s Bletchley Park surely came a close second, if not first. Known as Ultra, cracking German communications saved untold lives and helped turn the tide in the critical Battle of the Atlantic.

The Germans were so confident in the ability of their Enigma machine to produce unbreakable encryption that they never imagined the Allies could possibly be privy to their plans at all, let alone for much of the war.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill credited Ultra with nothing less than the defeat of Nazi Germany. The supreme Allied commander in Europe, U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, described Ultra as “decisive” to the Allied victory. Harry Hinsley, a Bletchley Park veteran and official historian of British Intelligence during the Second World War, said that while the Allies would have won without the code breaking wizardry, “the war would have been something like two years longer, perhaps three years longer, possibly four years longer than it was.”

It’s true that the Norden was considered top secret well into the war, but it appears the designation was overblown.

In his 2012 book Hell Above Earth: The Incredible True Story of an American WWII Bomber Commander and the Copilot Ordered to Kill Him, author Stephen Frater notes that it cost US $1.1 billion (in wartime dollars) to develop and manufacture the bombsight—two-thirds as much as the Manhattan Project and more than a quarter of the production cost of all 12,731 Boeing B-17 bombers.

But the Norden was in no practical way as secret as Ultra: both the British SABS and German Lotfernrohr 7 bombsights worked on similar principles, and details of the Norden were known to the Germans even before the war started.

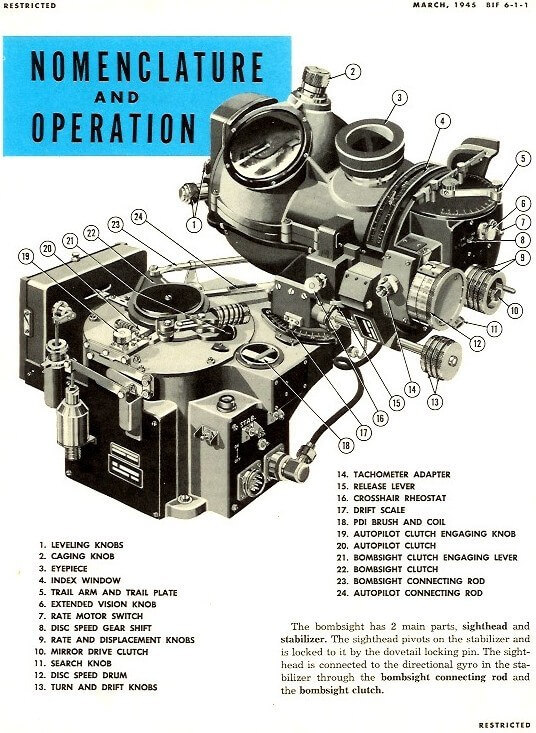

Nevertheless, bombardiers were required to take an oath during their training stating that they would defend the Norden secret with their lives. If their plane made an emergency landing on enemy territory, bombardiers were to shoot critical parts of the device.

After missions, bomber crews routinely placed the bombsight in a bag and deposited it in a safe known as the “Bomb Vault,” located in a secure facility known as the “AFCE and Bombsight Shop,” typically located in a Nissen, or Quonset, hut.

A page from the Bombardier’s Information File (BIF) that describes the components and controls of the Norden Bombsight. The separation of the stabilizer and sight head is evident

[Wikimedia]

The fact is, Herman Lang, a German spy who worked inside Carl L. Norden Inc., had met with German military authorities during a visit to Germany in 1938, and reconstructed plans of the bombsight’s confidential makeup from memory.

In 1941, FBI agents arrested Lang and 32 other German agents of the Duquesne Spy Ring, a Nazi espionage network headed by Frederick (Fritz) Duquesne that infiltrated U.S. workplaces, gathering intelligence and conducting sabotage. The case, which remains the largest espionage prosecution in U.S. history, convicted them all, with Lang sentenced to 18 years.

Authorities gradually downgraded the secrecy of the Norden bombsight as the end of war approached. In 1944, it was put on public display for the first time.

The Norden measured an aircraft’s ground speed and direction, which previously could only be estimated via lengthy manual procedures. It also improved on older designs by using an analog computer that continuously recalculated the bombs’ impact point based on changing flight conditions, and it had an autopilot that reacted quickly and accurately to changes in wind and other effects.

The popular boast at the time was that high-flying American bombardiers could drop a bomb into a pickle barrel. In 1940, Norden president Theodore H. Barth said that “we do not regard a 15-foot square…as being a very difficult target to hit from an altitude of 30,000 feet,” provided the bombardier was working with his firm’s new M-4 bombsight connected to an autopilot.

“That was stretching it considerably,” John T. Correll wrote for Air & Space Forces Magazine in 2008. “In everyday practice in 1940, the average score for an Air Corps bombardier was a circular error of 400 feet [122 metres], and that was from the relatively forgiving altitude of 15,000 feet [4,500 metres] instead of 30,000 [9,100].”

Indeed, American planners were well aware from the outset that the pickle barrel boast was bogus. Training and practice data showed that a heavy bomber at 20,000 feet (6,100 metres) had a 1.2 per cent probability of hitting a 100-square-foot target.

“About 220 bombers would be required for 90 per cent probability of destroying the target,” Correll reported. In 1941, Air War Plans Division Plan No. 1 forecast it would take 251 combat groups to achieve the desired destruction of Germany’s infrastructure, industry and Luftwaffe.

Boeing B-17G “Wee-Willie” of 323 squadron, 91st bombing group, falls over Kranenburg, Germany, after its port wing was blown off by flak. Only the pilot, Lieutenant Robert E. Fuller, survived.

[National Museum of the USAF/Wikimedia]

The Eighth Air Force landed 31.8 per cent of its bombs within 300 metres from an average altitude of 21,000 feet (6,400 metres), the 15th Air Force averaged 30.78 per cent from 20,500 feet (6,200 metres), and the 20th Air Force against Japan averaged 31 per cent from 16,500 feet (5,000 metres).

At the time Masters of the Air begins in 1943, about 20 per cent of bombs dropped by the Eighth Air Force hit within 1,000 feet (300 metres) of the aiming point.

Cloud cover was often blamed for the relatively poor results, although performance did not improve even in favorable conditions. Over Japan, bomber crews discovered perpetually strong winds—jet streams—at high altitudes. The Norden bombsight only worked in minimal wind shear.

Additionally, bombing altitudes over Japan reached 30,000 feet (9,100 metres), while most of the testing had been done well below 20,000 feet (6,100 metres). Higher altitudes had compounding effects on variables—the shapes of bombs and even different paints changed their aerodynamic properties. At the time, calculating the trajectory of bombs reaching supersonic speeds was a mystery.

While the RAF developed its own bombsight design, the head of Bomber Command, Air Chief Marshal Arthur (Bomber) Harris, had no illusions about pinpoint accuracy, opting instead for nighttime area bombing and mass destruction of German cities.

Area Bombing Directives instructed air crews to “focus attacks on the morale of the enemy civil population and in particular the industrial workers. In the case of Berlin, harassing attacks to maintain fear of raids and to impose A.R.P. [air raid precautions] measures.”

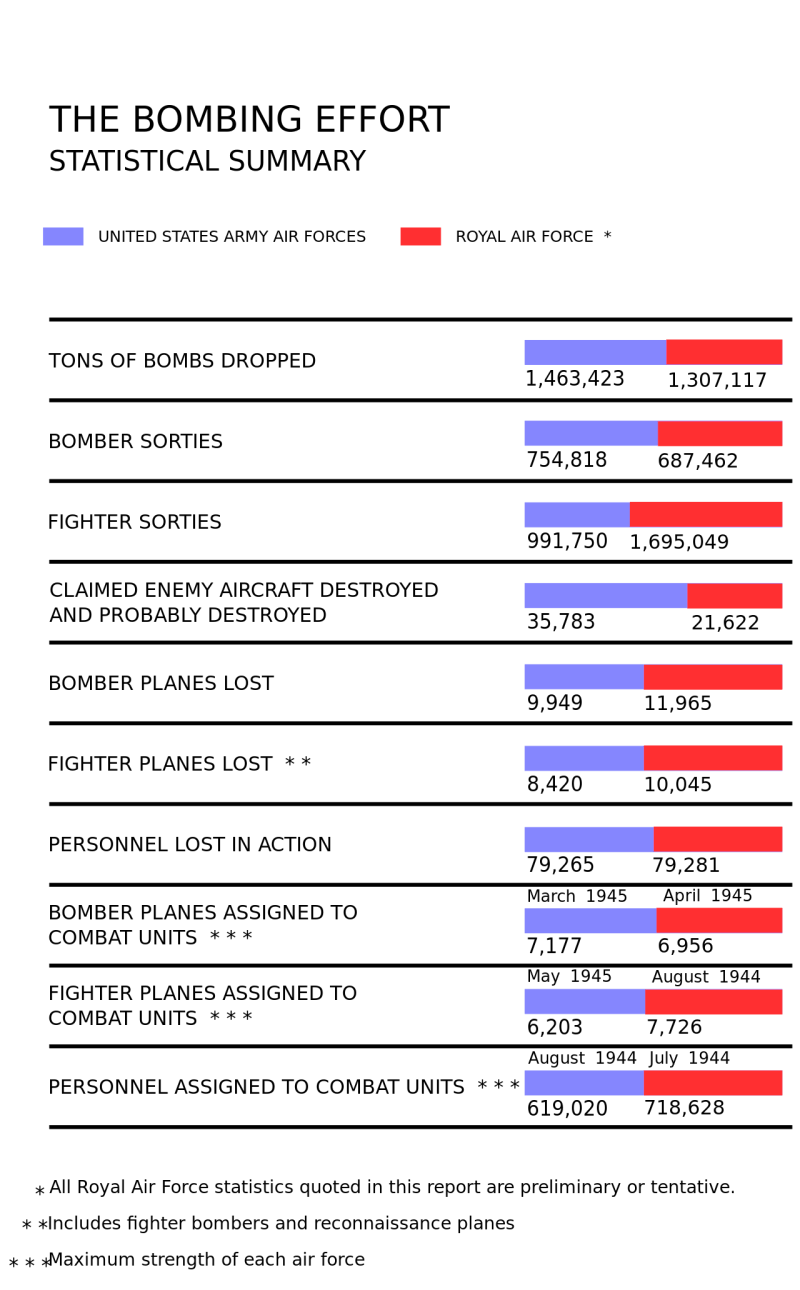

According to the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey, more than 1.4 million Allied bomber sorties dropped nearly 2.45 million tonnes of bombs on Germany and Nazi-occupied Europe. The number of Allied combat aircraft peaked at some 28,000; 1.3 million men served in air combat commands.

The combined American and British/Empire air forces ultimately destroyed virtually all of Germany’s coke, ferroalloy and synthetic rubber industries, 95 per cent of its fuel, hard coal and rubber capacity, and 90 per cent of its steel capacity, David L. Bashow wrote in Soldiers Blue: How Bomber Command and Area Bombing Helped Win the Second World War.

Estimates of German civilians killed in the campaign are 350,000-500,000. Some 3.6 million homes—about 20 per cent of German dwellings—were destroyed or heavily damaged. The number rendered homeless was around 7.5 million.

An Avro Lancaster bomber passes over Hamburg.

[IWM/Wikimedia]

The cost in lives and aircraft, whether American- or British-led, was exorbitant: 79,265 American (half of them Eighth Air Force) and 79,281 British and Empire aircrew were killed during the bombing campaign in Europe, the U.S. survey states (other sources put the Bomber Command figure at 55,573, or a death rate of 45 per cent). More than 18,000 U.S. and 22,000 British and Empire planes were lost or damaged beyond repair.

By another measure, some sources put the average life expectancy of a Lancaster crewman at 21 missions; a B-17 crewman was only expected to survive 11.

Keep in mind, the Americans didn’t join the war until December 1941; the Eighth Air Force launched its first heavy bomber mission against targets in occupied Europe on Aug. 17, 1942. Bomber Command had been conducting raids since May 1940—more than two years earlier.

Safely home, crewmen cheer on stragglers in a scene from Masters of the Air.

[Apple TV+]

The most common estimates of Japanese casualties in the Pacific firebombing campaign are 333,000 killed and 473,000 wounded. During six hours on the night of March 9-10, 1945, U.S. napalm killed as many as 100,000 people in Tokyo alone—nearly four times the typically accepted estimates of those who died in the Feb. 13-15, 1945, firebombing of Dresden, Germany.

The charred remains of Tokyo residents after the American napalm attack of March 9-10, 1945. Up to 100,000 Japanese are believed to have died in six hours.

[Photograph by Ishikawa Kōyō]

Canadian viewers are advised to watch this American production with a healthy dose of skepticism and, for a more balanced look at the bombing campaign with insights from those who were there, take a peek at the documentary Lancaster on Netflix.

Advertisement