An assortment of American nuclear intercontinental ballistic missiles at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

[USAF]

The clock is now closer to midnight than it has ever been.

The implications of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were still reverberating around the world when American physicist Hyman Goldsmith and artist Martyl Langsdorf got together to design a cover for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists—a non-profit organization that studies how to reduce human threats to existence.

The Soviets wouldn’t test their first nuclear device for two more years, and the first Pugwash Conference on Science and World Affairs, involving scientists, scholars and public figures committed to peace and disarmament, was still a decade away.

Known as the Chicago Atomic Scientists, the Manhattan Project veterans had begun publishing a mimeographed newsletter, and later a bi-monthly magazine, soon after the atomic blasts ended the war against Japan.

The cover of the June 1947 Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, featuring the Doomsday Clock at seven minutes to midnight.

[Wikimedia]

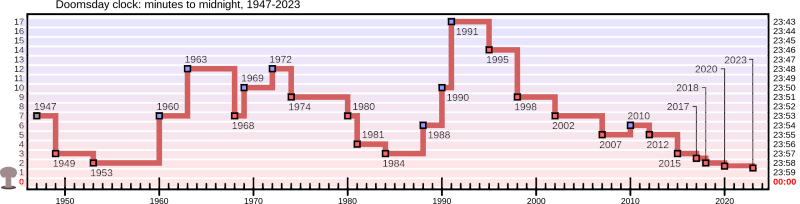

Assessed annually, the clock has been set backward eight times and forward 17. It’s been as far from midnight as 17 minutes, in 1991, and as close as 90 seconds, where it has stayed since January 2023, 11 months after Russia invaded Ukraine.

“The Bulletin’s clock is not a gauge to register the ups and downs of the international power struggle,” explained another Bulletin co-founder, the Russian-born American biophysicist Eugene Rabinowitch.

“It is intended to reflect basic changes in the level of continuous danger in which mankind lives in the nuclear age.”

The Doomsday Clock has stood at 90 seconds to midnight since January 2023, its highest threat level ever.

[Wikimedia]

“Midnight” and “global catastrophe”—or the threat to civilization—are determined by factors such as nuclear threats, climate change, bioterrorism and artificial intelligence.

The clock was set at two minutes to midnight in 1953, after the first detonation of a hydrogen bomb and again in 2018 after world leaders failed to address tensions related to nuclear weapons and climate change. During the 1962 Cuban missile crisis, it was set at seven minutes to midnight.

It went to two-and-a-half minutes in 2017, the first fractional time in the clock’s history. At the outset of Donald Trump’s presidency and rampant conspiracy theories, Bulletin scientist Lawrence Krauss warned that political leaders must make decisions based on facts, and those facts “must be taken into account if the future of humanity is to be preserved.”

The Bulletin itself called for action from “wise” public officials and citizens to try to steer humanity away from catastrophe while they still could.

A timeline of the Doomsday Clock since its inception in 1947. Numbers in left column refer to the minutes to midnight (catastrophe); at right column are the raw times. [Wikimedia]

It stayed there through 2019.

In 2020, the Doomsday Clock went to a then-record 100 seconds to midnight, where it remained through 2021 and 2022. The Bulletin’s executive chairman, Jerry Brown, said: “The dangerous rivalry and hostility among the superpowers increases the likelihood of nuclear blunder…Climate change just compounds the crisis.”

It was moved to 90 seconds in January 2023, largely on the risk of nuclear escalation following the Russian invasion of Ukraine—and subsequent comments by embattled Russian president Vladimir Putin, who suggested in the face of unexpectedly stiff Ukrainian resistance and surging materiel support from the West that all options were open as far as nukes were concerned.

Climate change, biological threats such as COVID-19 and risks associated with disinformation and disruptive technologies also factored in the decision to move the clock to an all-time high-risk status.

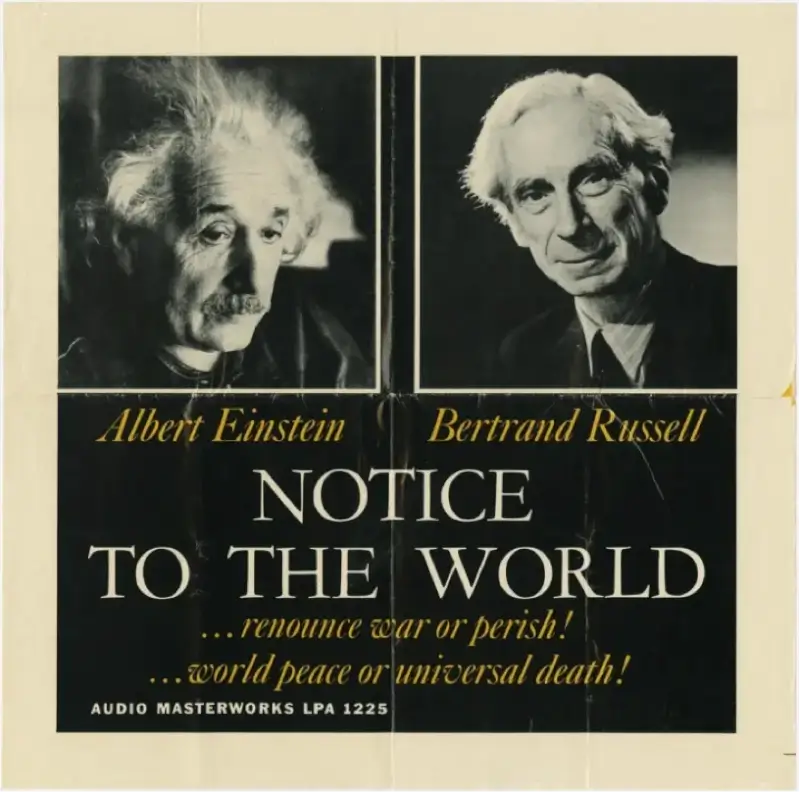

Albert Einstein and Bertrand Russell published their manifesto in July 1955.

[Unknown]

Their role escalated with the release of the Russell-Einstein Manifesto in London on July 9, 1955, by mathematician, writer and social conscience Bertrand Russell.

Coming amid rising Cold War tensions, it emphasized the dangers posed by nuclear weapons and urged world leaders to seek peaceful resolutions to international conflict. Eleven distinguished intellectuals and scientists signed the declaration. Albert Einstein did so just days before he died.

Shortly afterward, philanthropist Cyrus S. Eaton responded to the manifesto’s call for a conference, offering up his seaside compound in his birthplace of Pugwash, N.S.

“Your brilliant statement on nuclear warfare has made a dramatic worldwide impact,” he told Russell. The first session of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs was held in July 1957, bringing together 22 eminent scientists from 10 countries.

Nuclear disarmament would be a prevailing theme of the conferences, which—along with their founder, Polish-born physicist Joseph Rotblat—would jointly receive the 1995 Nobel Peace Prize “for their efforts to diminish the part played by nuclear arms in international politics and, in the longer run, to eliminate such arms.”

The conference’s first 15 years coincided with the Cold War’s greatest tensions: the Berlin Crisis, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Hungarian Revolution, the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia and the Vietnam War.

Pugwash, as the conferences became known, “afforded a rare channel of communication between scientists from East and West,” MIT’s Journal of Cold War Studies reported in 2018. “In subsequent years, it came to provide a forum for second-track nuclear diplomacy.”

Indeed, the Nobel committee noted that the Pugwash movement helped open communication backchannels during an era that alternated between silence and periods of high tension marked by threats and hyperbole between East and West.

It provided background work to the Partial Test Ban Treaty (1963), the Non-Proliferation Treaty (1968), the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty (1972), the Biological Weapons Convention (1972) and the Chemical Weapons Convention (1993).

Delegates gathered for the first Pugwash Conference in Nova Scotia in 1957.

[Unknown]

The Soviet Union’s last leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, acknowledged in a 2004 interview with The Journal of the Federation of American Scientists that the Pugwash organization influenced his decision-making.

There have been more than 60 Pugwash conferences and their primary goals remain the elimination of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction.

“It is good to know that the [conference] is an ongoing, vibrant project that continues to bring together concerned scientists who fully understand the responsibility to humankind,” Gorbachev said in a statement prior to the 50-year anniversary conference.

He called for “an intellectual foundation for agreements that would dramatically cut the arsenals of nuclear weapons on their way to their elimination and prevent an arms race in space. We need your brainpower, not just to analyze the problem, but to find solutions.”

The international community has negotiated some 40 arms control treaties and agreements since the Second World War, with varying degrees of success.

Limiting humankind’s penchant for self-destruction is a constant process. The roles of non-governmental organizations, scientists, independent thinkers and popular movements are fundamental to these processes and achievements.

Advertisement