But at the heart of Douglas’ fervour is an epic endeavour he started long before he owned Salient Tours or the British Grenadier Bookshop in the medieval town once known as Ypres. It’s called the Maple Leaf Legacy Project, a 27-year-old effort to procure and post photographs of each and every Canadian war grave.

What started as a one-man initiative evolved into an enormous undertaking by some 750 volunteers from several countries. They have so far documented more than 106,000 Canadian graves from the Boer War (1899-1902), the two world wars, the Korean War, United Nations peacekeeping missions and the Afghanistan war.

More than 120,000 Canadians who “died in the service of their country” are commemorated in the eight Books of Remembrance kept in the Peace Tower on Parliament Hill; nearly 117,000 of them were killed at war. Not all of the war dead have known graves—the resting places of about 28,000 Canadian soldiers are unknown, almost 20,000 of them died in the Great War.

“In this way, we hope to create a virtual National War Cemetery so that the thousands of relatives and descendants of Canada’s war dead, who may not be able to visit the grave in person because of the great distances involved, will at least be able to see a picture of the headstone and the inscription,” says the project website.

“So, I started reading about it,” beginning with They Called It Passchendaele: The Story of The Third Battle of Ypres And of The Men Who Fought by Lyn Macdonald.

“I have been reading about it ever since.”

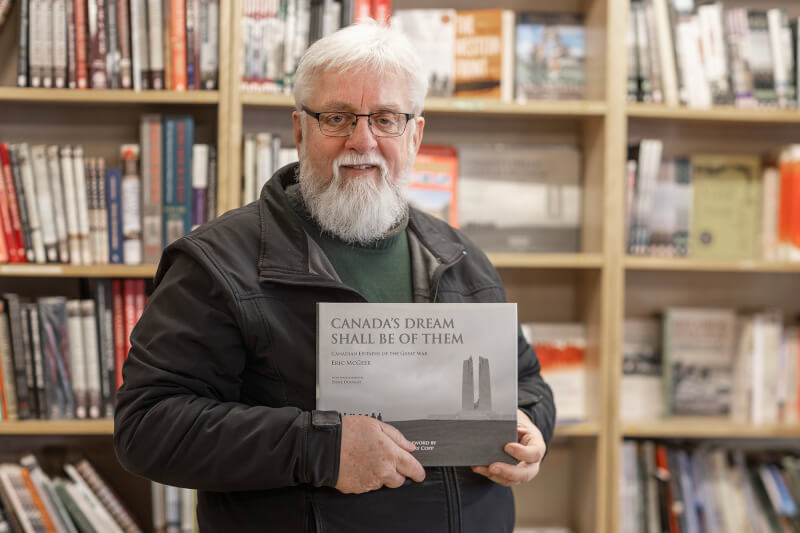

Indeed, his British Grenadier Bookshop around the corner from Ieper’s legendary Cloth Hall now contains as many as 1,500 new and used books, including collectibles. They fill the shelves alongside vintage bayonets and badges, bullets and bottles, ammunition boxes, helmets, swords, horseshoes, cutlery, rum jars, satchels, shrapnel and trench art. There’s even a warhorse’s feed bag.

“I hated it,” he says. “With me living in England, my access to the cemeteries in France and Belgium was limited to two days of a four-day weekend.

“After four years, in 2003, the opportunity came up to work in the shop, the British Grenadier Bookshop, in Ypres.”

The owner was about to open it as a base for his decade-old Salient Tours operation. “He needed someone to run the show for him here so he could go back to the U.K. and put his feet up and watch the money roll in. I worked quite happily for him…for five years and then I bought it from him in 2008.”

It was here in the fall of 1914 that Allied forces stopped the German advance, known as “the race to the sea,” and prevented the Kaiser’s troops from taking the coveted ports of Calais, 85 kilometres away along the English Channel.

Thus began almost four years of virtual stalemate in west Belgium and along 800 kilometres of trench works extending through France to the Swiss border. The impasse was punctuated around Ypres by five major battles fought in notorious mud and cold, including Passchendaele where, after three months of Allied offensive, Canadian troops made the final push into the ridgetop town a few kilometres northeast of Ypres.

Through it all, Ypres—now known by its Flemish name, Ieper (EE-per)—and surrounding villages and towns were reduced to rubble. The waterlogged fields were a network of jagged trenches. No man’s land and virtually everything else was pounded to pudding by millions of artillery shells.

About 74,000 Canadians visited Belgium in 2023; some 1,400 went to the Flanders area, the bulk of them history buffs, according to Visit Flanders, the area tourist office.

The region remains a treasure trove of war artifacts—some, such as unexploded poison gas and artillery shells are deadly; others, like twisted equipment and shattered helmets, reminders of the scale, brutality and cost of the fighting.

There are more subtle reminders, too, such as the distinctive stone jugs marked with the ““SRD”” of the British Supply Reserve Depot that meted out the daily rum rations in the trenches: a moment of peace and a pipe, a well-worn letter from home, a home-baked biscuit and, if you were very lucky, some Dundee marmalade.

“So many weird and wonderful militaria items have come in over the years,” he says. “Most I resell, but the strange, rare, fascinating pieces I will often keep for my collection.”

There’s the beer bottle from a brewery in Dachau, the German village where one of the Third Reich’s notorious concentration camps was located during the Second World War. The “Active Service Khaki Kombination Kandlebox” that served as a flashlight in the WW I trenches. The artillery fuse that evidently collided with another coming the other way. And helmets riddled by shrapnel.

Last year, a local came in and offered him a small rifle. Douglas had never seen anything like it.

“At first I almost didn’t take it,” he says. “I dismissed it as someone’s hunting rifle. There were no identification marks on it, it had no mount for a bayonet, and it was a single-shot rifle mechanism. In other words, there was no clip for five or 10 bullets like most military rifles had. This one would only take one round.

“The puzzling thing was that it had apparently been found in the fields around Hill 60/Mount Sorrel. So, basically, on the front line just outside of Ypres. The metal mechanism plate above the trigger was covered in surface rust so no markings were visible.

“So, I took a small brass wire brush to the surface and, lo and behold, the markings were there.”

It was a Martini-Enfield rifle with the British military broad arrow mark and a 1915 stamp. “Fantastic discovery and provenance.”

“It would take the same .303 bullet as the SMLE, but you don’t want this rifle in your hands if the enemy is charging at you. One bullet at a time and no bayonet,” says Douglas. “So, now I had a mystery on my hands.”

“Apparently though…it would often just leave a hole in the fabric and not set it alight. I can imagine the shooter getting very frustrated at this and in a fit of rage just pitching the rifle overboard to land in the muddy farm fields below.

“Or, perhaps the aircraft was shot down and crashed and the bits and pieces spread over a large area. Then some years later, someone walking the fields would have found it and kept it all these years until my friend bought it from one of the descendants of the original finder and sold it to me.”

While his Salient Tours focuses primarily on Ieper and surrounds, Douglas also guides visitors to Vimy, the Somme, Fromelles, Dieppe and Normandy. One of his guides takes tours to Verdun and Waterloo.

So, he called on his longtime driver, Mo. Mo knows the area well, but is not an actual guide. “He knows some things, but not all,” wrote Douglas. “Usually people are good about that. They just want to get out and see some sights and they realize it was last-minute.” And Douglas gives them a better price.

“So today, Mo, who is of Iranian heritage, took out a Uruguayan, a Colombian and a Mexican (who live in Holland) to learn about a war between the Germans, the French and the British, all while speaking English and arranged by a Canadian in Belgium. To paraphrase Louis Armstrong, sometimes, it can be a ‘wonderful world.’”

This is the last of an eight-column series on Flanders.

Advertisement