George Etherington resting on a hillside on the island of St. Vincent.[Royal Green Jackets (Rifles) Museum]

Born in Delaware in 1733, Etherington rose to the rank of captain in 1756 while serving in the Seven Years’ War. So, when he took command of Fort Michilimackinac, at the confluence of lakes Huron and Michigan, in 1762, he carried the confidence of British military superiority with him. But that wouldn’t last for long.

Etherington and his garrison were responsible for salvaging the tenuous relationship between the Brits, French and the Ojibwe and Sauk tribes, but even for Etherington, that was a big feat.

The Seven Years’ War had left a sour taste in the mouths of Indigenous Peoples since the Brits’ pre- and postwar policies were inherently anti-Indigenous. Many of the continent’s original inhabitants had sided with the seemingly friendlier French, making the loss all the more bitter. So, with Indigenous nations in a stalemate over the capture of Fort Detroit, the Ojibwe decided to make their move—this time, on the 30-year-old Etherington and with an almost unknown sport at the time: lacrosse.

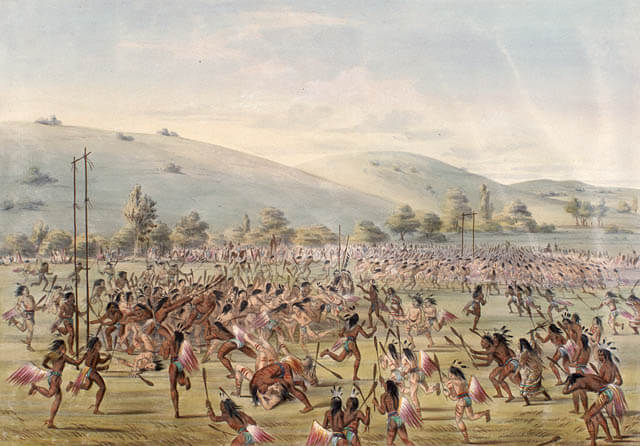

But Canada’s national “summer sport” looked nothing like today’s version. Invented in 1100 by Indigenous tribes in North America, the game was sometimes called “baggatiway” by the Algonquian until Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf gave it the name “lacrosse.” Regardless of its name, tribes would play the game on fields from 500 metres to three kilometres long for three days with up to a thousand players.

While a 72-hour workout might seem excessive, baggatiway was not just a sport; it was a rite of passage for Indigenous men to prepare for war with its own ceremonial and ritualistic ties. The meaning, however, would vary depending on which community hosted it.

But the Brits hadn’t paid much attention to the different cultural practices of Indigenous groups, so the Ojibwe used that ignorance to their advantage.

Indigenous Peoples playing an early form of lacrosse. [Library of Canada Archives]

In Britain, war was war, and sports were sports—mixing the two was the equivalent of sacrilege.

Local Ojibwe tribes Minweweh and Madjeckewiss invited Etherington to watch a lacrosse match between the two in honour of King George’s birth.

“…because you know, Aboriginals were all about celebrating the birth date of their foreign oppressor,” wrote the author of the All About Canadian History blog.

And to make it a sweeter deal, the game would be played on Fort Michilimackinac’s soil for Etherington’s “convenience.”

Now, some might say that unlike Etherington, present-day armchair historians have the advantage of hindsight, but that wasn’t required for the garrison commander to have his ears perked up. After all, a war was still on, and most boys who grew up in the colonies, Etherington included, had heard stories of Indigenous uprisings.

Still, Etherington was quite British despite fighting and being raised on North American soil. And in Britain, war was war, and sports were sports—mixing the two was the equivalent of sacrilege.

He was thereby suffering from what social psychology now calls “confirmation bias,” a tendency to process information by looking for information that is consistent with existing beliefs. Etherington ignored every soldier in his garrison who tried to warn him of this “Trojan Horse,” including respected fur trader Charles Langade.

The warnings became so frequent that Etherington issued a threat that if any man in his fort continued “gossiping” about the impending game, they would be locked up in Fort Detroit, no questions asked. It seemed Etherington was doomed to fate now.

As the wooden ball rolled to the fort’s gates, the Indigenous women revealed dozens of knives and steel tomahawks beneath their robes.

So, on June 2, 1763, Etherington and his garrison met with the 500 Indigenous “players,” even telling his soldiers to leave their weapons behind. While the odd sight of Indigenous women wearing stifling winter robes on a hot June day left some of the men scratching their heads, Etherington was preparing himself for an entertaining match, and as it kicked off, all seemed to be going according to plan—that is, until the wooden ball rolled to the fort’s gates.

As it did, the Indigenous women revealed dozens of knives and steel tomahawks beneath their robes. With Etherington’s 35 men weaponless and vastly outnumbered, the surprise attack left around 27 British dead and another dozen captive. Etherington himself was among the latter. The Brits had to negotiate with the Indigenous Peoples to get him back.

Even so, the Ojibwe successfully captured Fort Michilimackinac, making it the fifth fort to be claimed by Indigenous groups. The Ojibwe’s hold on the fort would eventually fall, however, being recaptured by the British a year later.

Advertisement