He signed in the wrong place, but representing Canada at Japan’s surrender was still a career highlight for soldier-diplomat Lawrence Cosgrave

Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave signs the Japanese Instrument of Surrender on Canada’s behalf aboard USS Missouri on Sept. 2, 1945. [Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images/940109456]

Laughter rippled over the waves of Pearl Harbor. It was a breezy, cloudless, perfect Hawaiian day not so very long ago.

Tourists, clad in all sorts of loud and tasteless vacation getups, clustered around a display case on the canvas-topped surrender deck of the battleship and Second World War icon USS Missouri.

Now a museum, the 45,000-tonne decommissioned warship in Pearl Harbor is a pantheon for naval history buffs and even the slightly bored sightseers who overrun Oahu.

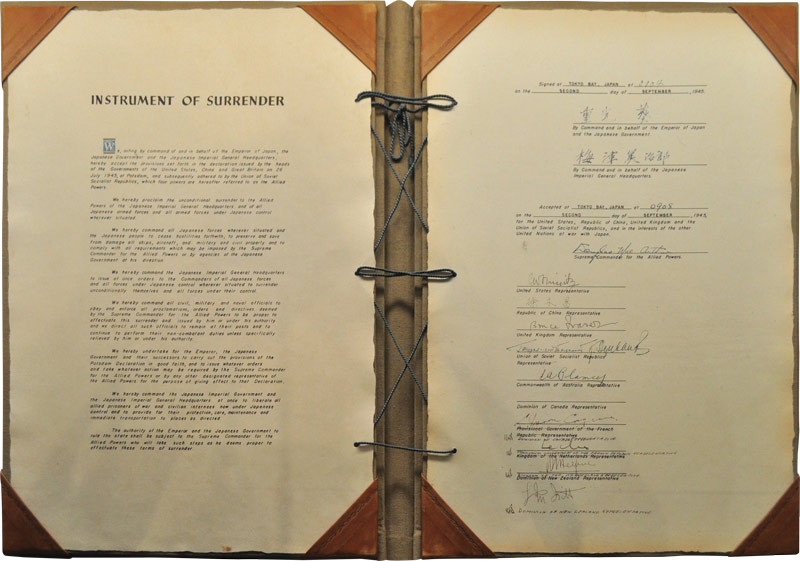

“I am not supposed to say this, but the Canadians signed on the wrong line,” the museum guide said from behind dark, oversized sunglasses.

He aimed a laser pointer—the kind used to drive cats out of their minds—at copies of the formal surrender, the documents that ended the most destructive war in history.

Both sets—Allied and Japanese—were sheathed in the glass and wooden case.

The red dot hovered over an empty line where the signature of the “Dominion of Canada Representative” should have been. Significantly, it was the Japanese Instrument of Surrender that was bungled.

The blank line can be seen on the document’s right-hand page, along with Lieutanant-General Richard Sutherland’s handwritten corrections. [Diplomatic Record Office/Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan)]

Colonel Lawrence Moore Cosgrave, Canada’s impromptu representative at the surrender ceremony on Sept. 2, 1945, had signed his name just below the appropriate spot, on the line reserved for the French delegate.

The emperor had to make do with a marked-up copy.

The mistake forced the subsequent signatories to also put their names on the incorrect lines, up to the New Zealand representative who put his signature on the blank portion at the bottom.

The dismayed Japanese delegation refused to accept anything less than an unblemished copy. In stepped U.S. General Douglas MacArthur’s chief of staff, the notoriously mercurial Lieutenant-General Richard Sutherland, who hand wrote corrections to the Allied titles under each signature.

He tersely dismissed the Japanese, who retired to their launch in Tokyo Bay clutching the disfigured certificate that acknowledged their unconditional surrender. The emperor had to make do with a marked-up copy.

Sutherland’s quick thinking turned what could have been an embarrassing diplomatic incident into a minor, now largely forgotten historical footnote, and—almost eight decades on—a punchline.

“Honest mistake,” one of the tourists hollered, amid the laughter.

The tour guide, a gruff former sailor, was in a charitable mood.

“He was the junior officer among the flag ranks,” he said, speaking like an enlisted man. “He was a colonel. He was among admirals and generals. He only had one eye. And he was nervous. So, the Canadian signed below the line. So, don’t pick on the Canadians, OK?”

Cosgrave is oft-remembered for his signature misstep, but he was, in fact, a dedicated soldier and diplomat: he served alongside Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, earned the DSO and Bar, and lost the vision in one eye at Ypres. [DND/LAC]

History can sometimes be cruel and capricious. When Cosgrave died in 1971, The New York Times noted his passing with a tongue-in-cheek reference to the kerfuffle. He was notable, the obituary said, as the man who signed on the wrong line in 1945.

More than four decades after his death, on the 70th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in 2015, The Globe and Mail took an even harsher line, describing him as the man who almost “botched the surrender document.”

What a way to be remembered.

It is an unfortunate one-dimensional portrait of a man who, in his day, was the quintessential soldier-diplomat.

War had made a deep impression on him. Not surprising, perhaps, given he was a contemporary and comrade to Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae. Later in life, Cosgrave claimed McCrae wrote “In Flanders Fields” on a scrap of paper on Cosgrave’s back during a pause in an artillery barrage.

Cosgrave was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and Bar (in 1916 and 1918) and the French Croix de Guerre. He was wounded in action during the Second Battle of Ypres, costing him the vision in one eye—a disfigurement some, including the tour guide, suggest led to the faux pas.

Like many men of his generation, Cosgrave was haunted by the butchery of the Great War and was a man who, throughout his life, never ceased to be moved by the human condition and the cruelty we inflict on one another. He tried to exorcise those demons with his pen.

In the immediate aftermath of the Armistice of 1918, Cosgrave wrote a nonfiction—for lack of a better description—short story (or overly long essay) that falls somewhere between first-person account and sermon.

At 36 pages, Afterthoughts Of Armageddon: The Gamut Of Emotions Produced By The War, Pointing A Moral That Is Not Too Obvious cannot be considered a book, or nonfiction memoir. It may not have even had an editor.

There is, at times, a narrative and emotional detachment to the piece, almost as if some experiences and feelings were so profound, and he was so angry, that he was doing everything in his power to control himself—and failing.

Cosgrave had entered the Great War with gauzy romanticized notions. By his own admission, he approached the front in the winter of 1915 “with a sportsman’s indignation” as though it was some kind of benign contest.

The waves of chlorine gas that swept over the Canadian and Algerian trenches at Ypres in mid-April led to a brutal, unexpected awakening. Years later, he described in almost reverent terms the “silent, menacing, all-devouring, grey-green cloud of poison gas.”

He watched the attack unfold with unrestrained agony and helplessness.

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Allied Commander, delivers a speech to open the surrender ceremony aboard Missouri. Cosgrave is behind him, third from left, the lowest ranking Allied officer to sign the surrender documents. [U.S. Navy/C-2717/Wikimedia]

“Men in their splendid strength sinking to the ground in dreadful contortions—dying after hours in agony—their dying words crying curses upon the fiends in human form who could be such damnable cowards.”

It was his first, but not his last, brush with survivor’s guilt. Cosgrave said he learned to hate on that day, his language filled with all sorts of Victorian adjectives and allusions. The years he spent in “soul-deadening trench warfare” left an indelible mark.

“For man was forced to think and learn to know himself, to analyze his deepest thoughts, and, sometimes, perhaps, in those solemn moments when one hovers between life and death, a few of us may have seen beyond the veil, where all things are known.”

The narrative is short on specifics throughout, includes the kind of lurid descriptions we’ve come to expect in modern memoirs, and is long on reflection which—while pessimistic, sometimes questioning God and morality—

does not quite rise to the level of poetry.

He endures the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele in “a cocoon of hate.” His faith hangs by a slender thread and you feel the dismay, despair and fear as he writes about the last great German offensive, in March 1918, when it seemed all would be lost.

Victory, in the end, was “our great reward,” Cosgrave wrote. There was grim resignation and little joy. He spoke of the hardened survivors as men “who learned to know ourselves—to believe in our fellow men—to know right from wrong and to have sympathy for the world’s weaknesses and failings.”

Within the final few pages, one detects the seeds of weary hope. As part of the occupying army in Germany, he listens to two children singing “O Heilige Nacht” (O Holy Night) outside his window on Christmas Eve in 1918.

Writing in the third-person, Cosgrave knew at that moment “that all was well; that, at last, the world was safe for all babes of the world—the coming splendid world—which, thank God and the men today, would never undergo the agony, the pain and the heart torture of another such Armageddon.”

As it turned out, the world was not safe and many of those “babes” would be sacrificed in an even bigger, more horrific war.

Did those words run through Cosgrave’s mind as he rode through the shattered streets of Yokohama, across the bay from Tokyo, a quarter of a century later in the days following the Japanese surrender? He viewed it all with sadness and dismay, his writings showed.

“The thousands of Japanese living in the flattened ruins of Yokohama in flimsy huts of rusty tin sheets—scooping water from the puddles to exist—a taste of the destruction Japan caused in so many countries,” he wrote to a friend at the Australian embassy. Cosgrave had been a trade commissioner in Melbourne and Sydney and then Canada’s military attaché to Australia.

“The dull impassive faces of the population passing Allied troops. Japanese police at every street corner carrying on their duties. The lack of any real sustaining food—seaweed and grasses being a common dish with only fish every three days to supplement. The women clad in shoddy army trousers and shirts—no more colourful kimonos.”

The utter devastation of Yokohama, a city he had known before the war and perhaps even loved, filled him with awe as he toured the area arranging for the return of Canadian prisoners of war interned on the Japanese home islands.

With top-hatted foreign affairs minister Mamoru Shigemitsu and Gen. Yoshijiro Umezu, chief of the army general staff, at the fore, representatives of the Empire of Japan stand attentively on Missouri’s deck during the formal surrender. [Naval Historical Center/C-2719/Army Signal Corps Collection/U.S. National Archives/Wikimedia]

“Yokohama is a city of the dead,” he wrote in a series of incomplete sentences, as though his senses had been overwhelmed. “The dreadful effect of modern firebombing—fusing glass, iron and household items into complete nothingness. The shocking old trams—hopelessly dilapidated which were once Yokohama’s pride.”

Letters to colleagues at the embassy made a point of saying that old business contacts, bankers and exporters should be notified that their branch offices were still intact (although the Canadian Pacific Railway steamship office had been converted into a “hot night spot” in the war years).

Having lived in the Far East as a trade representative in Shanghai and Australia, he had many business connections, friends and memories. In fact, unlike some of the generals and admirals with whom he stood shoulder to shoulder on the deck of Missouri, Cosgrave had a personal relationship with some of the Japanese representatives who arrived to make the capitulation complete.

The defeated empire’s foreign affairs minister, Mamoru Shigemitsu, who signed the instrument of surrender, had been a diplomatic contact in Shanghai in the early 1930s. The two had co-operated, along with other western nations, in the brokering of a ceasefire between warring Japanese and Chinese forces.

It has been reported the two men smiled with mutual recognition on Missouri’s deck before Shigemitsu once more became stern and serious.

Cosgrave made no mention of his historic faux pas in his official typewritten report back to the Canadian embassy in Australia.

His recollection of the day was vastly different and more personal. It was written hours after the event in a cabin on the liberty ship USS General S.D. Sturgis, which had carried officers and officials of the United States, Australia, Canada, China, the Dutch East Indies and the Philippines to the surrender ceremony.

In his note to the embassy, Cosgrave simply listed those who signed and in what order and wrote that “the Allied representatives made a colourful impressive group.”

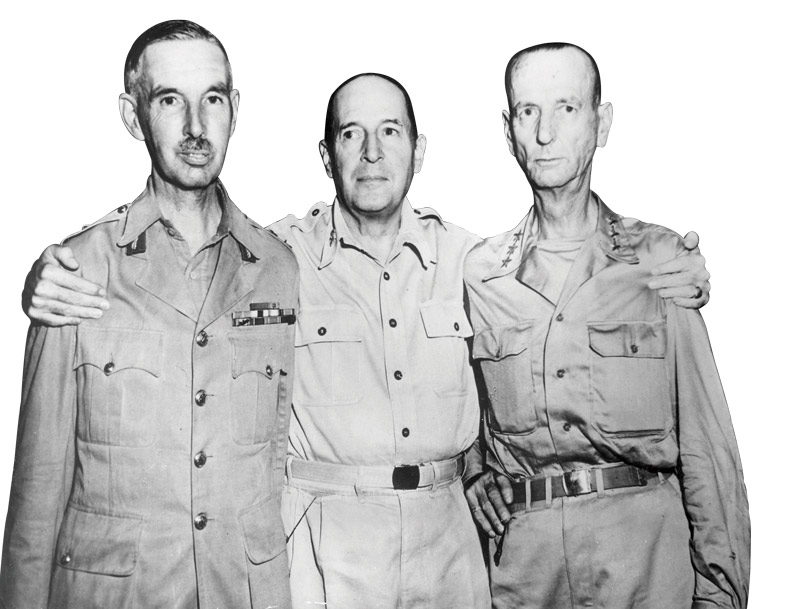

His notes did reflect the sense he was in august company. But instead of being awed by MacArthur or Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, his attention was drawn to the emaciated figures of newly freed Major-General Jonathan Wainwright, ill-fated commander of American troops who surrendered on Bataan in 1942, and Lt.-Gen. Arthur Percival, defeated British commander in Singapore.

There was no one more senior who could make it to the surrender in time.

Both had been freed and flown in to formally witness the Allied triumph.

MacArthur at his headquarters in Yokohama, Japan, with British Lt.-Gen. Arthur Percival (left) and U.S. Lt.-Gen. Jonathan Wainwright following their release from Japanese captivity at war’s end. The pair had been taken prisoner after their respective forces were defeated by Japan in 1942. [Keystone/Getty Images/3167637]

Cosgrave wrote of “the famous General Wainwright” and was deeply touched when MacArthur presented fountain pens used to sign the instrument of surrender to both former prisoners.

A letter to an embassy colleague was punctuated with a sense of wonder that he had been there at all. Since Canada had played only a small role in the Pacific war, there was no one more senior who could make it to the surrender in time.

“I shall remain eternally grateful to the authors of my appointment to this historic ceremony,” Cosgrave wrote, adding wistfully, “Twill always remain the highlight of my not uneventful career.”

Advertisement