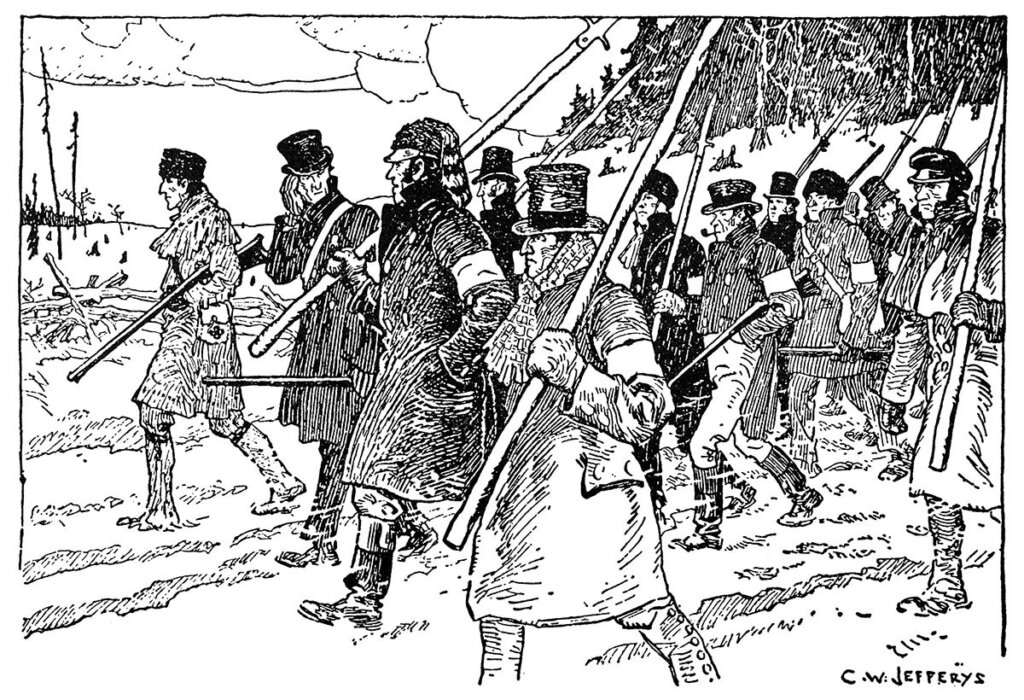

Rebels attack British forces at Dickson’s Landing, Upper Canada, in 1837-38. [LAC/R13133-296]

During my visit, the sky had now cleared of rain clouds and the sun was out. I walked a trail leading to the water’s edge where some of the fugitives sought shelter in the trees and bushes. Nils von Schoultz, the Hunter’s captain during the raid, was captured somewhere along the shoreline on Nov. 16. He and other survivors must have been tempted to swim across the river to the American shorline. But to my knowledge, none tried.

In my own timeline, with the warmth of summer I judged a desperate escape across the river feasible for an able swimmer. But in mid-November, starving and wounded, it seemed less likely. It was the frigid river or the bayonet of an excited Dundas or Glengarry county militiaman.

Of the 250 raiders who crossed the St. Lawrence from the U.S., more than 50 were killed. They were buried in a common grave near the site. The wounded and survivors were taken prisoner. Of these, 11 were executed, including von Schoutz. Dozens more were exiled to Van Diemen’s Land (present-day Tasmania). British and Canadian forces paid a price, too, with 16 dead and 60 wounded.

In looking across to Ogdensburg and the U.S. shoreline, I couldn’t help but wonder what brought these men here. Records compiled for the captured Americans indicate they were labourers, carpenters, blacksmiths and coopers. In other words, they were everyday people. Was this raid really an altruistic, albeit misplaced call to export liberty and the ideals of the revolution? Or merely war’s siren call to adventure?

I understood the Canadian response to the invasion. There’s something primal and instinctual about defending one’s homeland from a foreign army. It needs little explanation. But what motivated the Hunters to cross the border? To properly understand the Battle of the Windmill, I felt I needed to visit its origins.

Was this raid really an altruistic, albeit misplaced call to export liberty and the ideals of the revolution? Or merely war’s siren call to adventure?

I’ve never felt apprehensive going to the U.S. before, yet this time, in the months following U.S. President Donald Trump’s election, seemed different. As the international bridge hove into view, those recurrent Buy Canadian radio ads, Canada Not For Sale caps, and all the elbows-up and anti-51st-state jingoism played with the worst of my imagination. As I crossed the bridge, I realized I was the only traveller on it.

The border guard was a man who looked like he took his job seriously. He waited in his booth silently with an outstretched hand. I produced my passport and the hand stayed suspended just a second longer than seemed necessary. He appeared genuinely puzzled that I would want to visit historical sites in Ogdensburg.

“Where else are you going?” he asked.

“Just Ogdensburg.”

“Well, enjoy your stay.” He handed my passport back and I was on my way.

After paying the bridge toll, I was now unmistakably in the republic. Quite literally every other house proudly flew the Stars and Stripes. There were also plenty of Trump/Vance 2024 flags and several yellow “Don’t Tread on Me” Gadsden banners with its symbolic revolutionary rattlesnake.

During the 1838 raids, this part of the New York frontier along the St. Lawrence and Lake Ontario was a hotbed of Hunter activity. On prisoner rolls compiled after the battle, Jefferson County, Oswego, Ogdensburg and Syracuse appear repeatedly. To partially explain the willingness of so many to join the invasion, historians refer to a harsh economic downturn that gripped the region.

But there were also the true believers. Exiled Canadian rebels such as William Lyon Mackenzie drew crowds numbering in the thousands when drumming up sympathy and support for the rebellion’s cause. A newspaper article from the time captures one such meeting where Mackenzie was the featured speaker: “Every foot of the house, from the orchestra to the roof, was literally crammed with people—the pit was full—the galleries were full—the lobbies were full—the street was full—and hundreds obliged to go away without being able to gain admittance.”

In December 1837, William Lyon Mackenzie led a group of rebels to attack York, present-day Toronto. [LAC/1972-26-706]

Fort de la Presentation, in Ogdensburg, N.Y. [Clarkson University]

I took a short footbridge to Lighthouse Point, a narrow spit of land that pokes into the St. Lawrence River and has a panoramic view. From here, I took in the full scope of the battlefield on the Canadian shore, from present-day Prescott, Ont., to the red-topped windmill and the fields and treelines in between. A mile distant and almost directly across the river, Fort Wellington squatted on the opposite shore. The upper storey of a white blockhouse peeking above earthen walls sloped down to a concealed dry moat. Even from this distance, it looked intimidating. Given the casualties incurred in dislodging the Hunters from the windmill, one can only imagine the casualties that would have been sustained if the British had had to retake the garrison. Had Hunter reinforcements been able to aid their countrymen, the task of dislodging the invaders may well have proved impossible.

Lighthouse Point is where Americans watched their countrymen embark on the Great Northern Hunt, as it was called. There was apparently something akin to a festive atmosphere among the spectators, at least for the first couple of days. As the siege wore on, the mood must have soured. Trapped men in the windmill would eventually come to look upon their countrymen with a bitterness and a question: Where are the reinforcements? By then I think they knew how their adventure would end. Growing shadows on the ground told me that my time was up as well.

I came to both shorelines hoping to better understand the tumultuous and deadly events along the border in 1838. I didn’t expect, however, to get a better insight into my own time. This border is once again playing heavy on the minds of Canadians. I’ve sometimes wondered why the new political lexicon of annexation, tariffs and a 51st state elicits such emotion and even fear, when it sounds more like political posturing and bluster to me. Perhaps it’s because history echoes through time. Maybe Canada’s subconscious remembers times such as 1838 and the windmill, when elbows up meant quite a deal more than it does today.

Advertisement