The Battle of the Windmill National Historic Site near Prescott, Ont., where some 250 Americans attempted to invade and “liberate” Canada from the British. [Dennis G. Jarvis/Wikimedia]

The Battle of the Windmill National Historic Site is located only an hour’s drive from Ottawa. It’s where, in 1838, some 250 armed American invaders rode the momentum force of manifest destiny northward, only to meet a violent end at the hands of British regulars and Canadian militia. The battle itself gets overshadowed figuratively by the War of 1812 and geographically by nearby Fort Wellington. Yet, I’ve always been intrigued by it and the question: Why would hundreds of people pick up their rifles, cross an international border and invade a country that they were not at war with?

I took backroads through farmland and small villages built around old mills and churches to get to the battlefield. The rain I had been running from came and went. At an area coffee shop, I overheard an older man with a Canada Not For Sale cap tell acquaintances that the crops in these parts “needed the water.” Heads nodded around him. I carried on. Bucolic roads were taking me through Loyalist country and into this penumbra of largely forgotten Canadiana.

At 18 metres high, the windmill tower stands like a sentry over the St. Lawrence River. It’s an impressive structure for the time it was built (1832) and, notwithstanding its conversion to a lighthouse in 1872, its base appears much the same now as it did in 1838.

The American raiders, Hunters as they called themselves, had originally planned on seizing Fort Wellington, 2.5 kilometres away, to use as a base to liberate Canada. The landing, however, was botched and they arrived at Windmill Point instead. At the time of the battle, there was a large stone tavern and several dwellings making an outer perimeter around the tower. With walls a metre thick that were largely impervious to small cannon fire, the stone stronghold wasn’t such a bad plan B for the would-be liberators.

I went inside the old windmill and signed the visitors’ log. It was more spacious than I had imagined, with an interpreter’s desk, racks of uniforms for children to wear and a display of artifacts from the battle. You feel almost as if you’re in a castle while taking the stairs upward. Its windows provide sightlines in all directions. From its upper floors, American snipers had unobstructed views of the battlefield and would have been able to see every British move as it happened. At the outset, this served the Hunters well.

A view of the Canadian shoreline from the old windmill. [jockrutherford/Wikimedia]

At the uppermost windows, I imagined the Americans looking anxiously to routes similar to the country roads I had travelled earlier, awaiting the promised stream of oppressed Canadians flocking to the banner of liberty and republican government. They never came.

In fact, sources from the battle show the Queen’s professional soldiers restraining the local Canadian militia when American prisoners were taken. If there was any sympathy for the Hunters, or pirates as they were often called on this side of the border, it wasn’t present during or after the battle.

Next, I cast my gaze to the opposite shore and the town of Ogdensburg, N.Y. For four days the martial contest played out in front of American spectators and sympathisers who had come to watch the battle. They were close enough to hear the thunder of cannons, muffled shouts and cracking muskets, but not close enough to see the brutal reality of war.

American snipers had unobstructed views of the battlefield and would have been able to see every British move as it happened.

During the first day of the raid, small American boats brought supplies and reinforcements, including cannons, to the docks at Windmill Point. By the second day, this supply line over the St. Lawrence had been severed with the arrival of British and American naval vessels, as well as the presence of American regulars in Ogdensburg who were tasked with upholding U.S. President Martin Van Buren’s official policy of neutrality.

With resupply across the river blocked, the Hunters, meant to be the mere vanguard of a much larger force, found themselves trapped in a hostile land. The surge of Canadian volunteers promised to join their cause amounted to nothing more than lies carried on the November wind. The Hunters, now ironically the hunted, were surrounded and forsaken. Their salvation on the American shore may well have been 100 miles distant for all the good of its proximity.

The siege grinded along for a few more days, while British reinforcements swelled the ranks of its forces to 2,000 men. On Nov. 16, an attack pushed the Hunters from the outlying buildings, some of which were torched, and into the tower and shoreline. All the while, the windmill was bombarded from land and water. Casualties mounted. Finally, a white flag of surrender appeared from one of the windows.

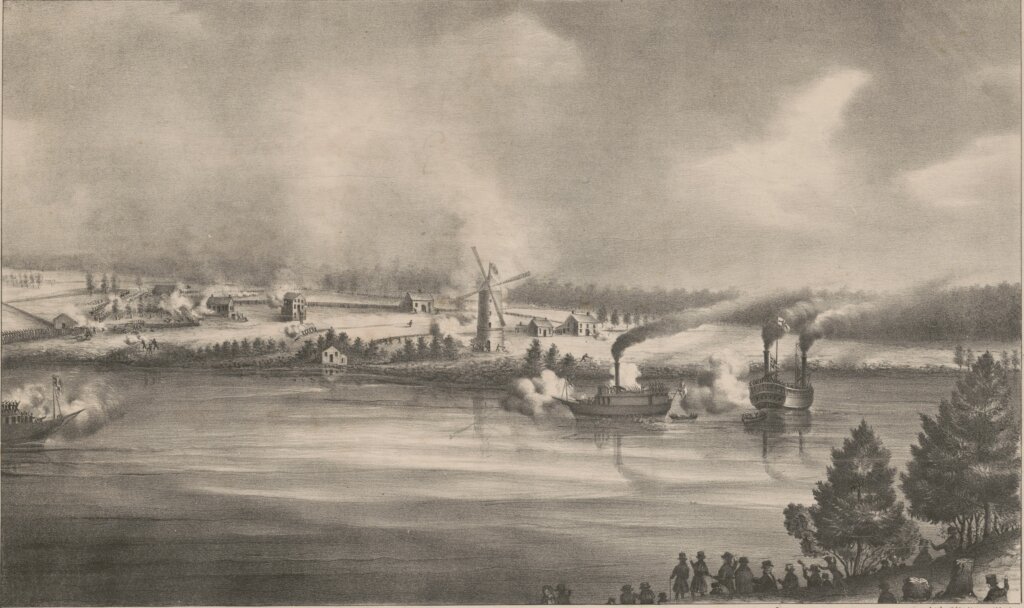

A lithograph depicting Nov. 13, 1838, a few days before the Hunters’ were defeated at Windmill Point. [Library of Congress/Wikimedia]

Advertisement