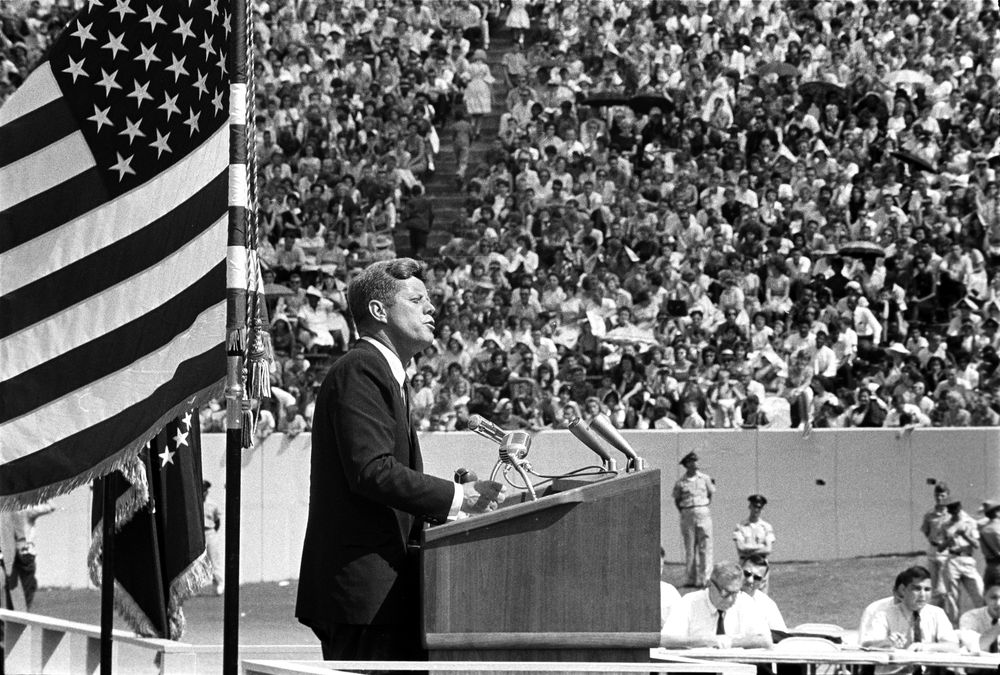

President John F. Kennedy speaks at Rice University on September 12, 1962. [NASA]

He was speaking to a crowd of 40,000 at the Rice University football stadium in Houston, many of them wide-eyed schoolchildren, their heads filled with visions of astronauts and rocket ships, space capsules and starscapes.

The first manned missions of the Mercury program were drawing to an end when Kennedy spoke, and the Apollo program was already in its early stages. Destination: the moon.

It was the speech in which Kennedy declared that America would land a man on the lunar surface by decade’s end “and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

Those were different times, at least in the public mind: idealistic, hopeful, prosperous and unified. Americans were in the grip of Cold War rivalry. It was also an age when science was at the forefront of public discourse.

Kennedy declared the space race to be a quest for knowledge and progress, a race that must be won because “space science, like nuclear science and all technology, has no conscience of its own.”

“Whether it will become a force for good or ill depends on man, and only if the United States occupies a position of pre-eminence can we help decide whether this new ocean will be a sea of peace or a new terrifying theatre of war,” he said.

“I do not say that we should or will go unprotected against the hostile misuse of space any more than we go unprotected against the hostile use of land or sea, but I do say that space can be explored and mastered without feeding the fires of war, without repeating the mistakes that man has made in extending his writ around this globe of ours.

“There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful co-operation may never come again.”

Even as he spoke, however, Kennedy must have known what the average American probably did not: the horses were already out of the barn or, to put it more to the point, the satellites were already out of the silos.

Kennedy’s predecessor, Dwight D. Eisenhower, was deeply engaged in the security implications of space technology and had launched a network of spy satellites starting in the mid-1950s. They were photographing Soviet installations well before Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit Earth.

Soviet pilot and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to journey into outer space when his Vostok spacecraft completed one orbit of the Earth on April 12, 1961. [Wikimedia]

Indeed, it was Eisenhower—a warrior and career army officer notoriously mistrustful of the military—whose blueprint for the peaceful exploration of space shaped the future of cosmic exploration to this day.

“From his long experience with the military, and the inexorably growing power of what he called the military-industrial establishment, he also knew that giving the job to the military services was not an option,” according to the online Encyclopedia Astronautica.

“They would squabble endlessly between themselves—each service already had its own planned satellite, man-in-space, and man-on-the-moon projects in the works.”

Scientific space projects would inevitably be the first things cut or cancelled when annual military budget priorities came up—not military endeavours.

Eisenhower proposed the creation of a civilian space agency to Congress in April 1958. The National Aeronautics and Space Agency (NASA) was formed.

“He would rip out of the military those parts of it that were mainly devoted to fundamental rocketry or space research,” says the encyclopedia. “Most notable of these were the Army’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech and [Werner] von Braun’s rocket team at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama.”

Other research projects were cancelled or transferred to NASA—and there were many, including air force rocket development; Pioneer moon probes; the orbital manned capsule; the army’s Explorer satellite; the Saturn I heavy launch vehicle; a suborbital manned capsule; and navy booster rocket and satellite projects.

The military would still pursue its own space programs, and it continued to push for a manned role in space and the deployment of combat spacecraft in orbit.

“The wisdom of Eisenhower’s choice was indicated by the fact that, despite the expenditures of hundreds of billions of dollars on these projects, not one of them reached the flight-in-orbit stage,” said the encyclopedia. “When the budget crunch came, military space projects were always the first to go.”

A resolution discouraging deployment of weapons of mass destruction in space was first tabled in the United Nations in 1963 after the Americans and Soviets made statements saying they had no intention of orbiting such weapons, installing them on celestial bodies or stationing them in outer space.

In 1967, the two superpowers ratified what’s become known as the Outer Space Treaty, roughly based on a pre-existing Antarctic agreement. Besides banning weapons deployments in space, it limited the use of the moon and other celestial bodies exclusively to peaceful purposes.

In 1983, President Ronald Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative, a space-based missile defence system that threatened to weaponize space and upset the balance of mutual-assured destruction that existed between the nuclear arsenals of the United States and Soviet Union.

Scientists determined the technologies involved in the initiative were decades away from reality and the controversial project was ultimately shelved.

Last June, U.S. President Donald Trump announced the formation of a “space force,” a new branch of the United States military dedicated to fighting wars in—you guessed it—space.

Matthew Overton, executive director of the Conference of Defence Associations Institute, says Canada should follow suit with what sounds an awful lot like a militarized version of what is already represented in the Canadian Space Agency.

Overton was vague about what the point of a Canadian space force would be beyond benefiting the institute’s benefactors—defence contractors including General Dynamics, Lockheed Martin, Pratt and Whitney, and Raytheon.

“At some point, we might like to think about a space force,” he told Postmedia. “Thinking about space as a separate entity in itself that deserves attention and expertise, I think is a good idea.”

He said Canada need not rush into anything. He suggested it should first develop a centre of excellence on space knowledge. But hasn’t the Canadian Space Agency, not to mention NASA and many others—which all have military components—filled that role, with distinction, for decades?

Commander Chris Hadfield (second from left) with the Expedition 34 crew in the Kibo laboratory aboard the International Space Station in April 2013. [NASA]

A “space force” conjures up images of The Thunderbirds, the marionette-driven 1960s television series whose (unintentionally) comical if not earnest puppets comprised a force of privately funded do-gooders operating on land, sea and in outer space.

The reality would inevitably be somewhat less altruistic and peace-fostering.

Defence Minister Harjit Sajjan’s office issued a statement saying that “space-based capabilities have become essential to Canada’s operations at home and abroad.

“That is why Canada’s defence policy…commits to investing in a range of space capabilities such as satellite communications, to help achieve global coverage, including the Arctic…. Canada will continue to promote the peaceful use of space and provide leadership in shaping international norms for responsible behaviour in space.”

Advertisement