Ernie Verhulst was eight years old when the Germans invaded his native Holland. He has lived in Canada for more than six decades. [Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

Ernie Verhulst’s first glimpse of the Luftwaffe came on May 10, 1940. He was eight years old and the significance of the Nazi advance across Europe had not been lost on anyone in Rotterdam, Netherlands.

His parents and their neighbours in the rowhouses around the city’s Charlois district had prepared for the German invasion, taping windows and cutting gates into their garden walls to facilitate escape routes in case of bombardment.

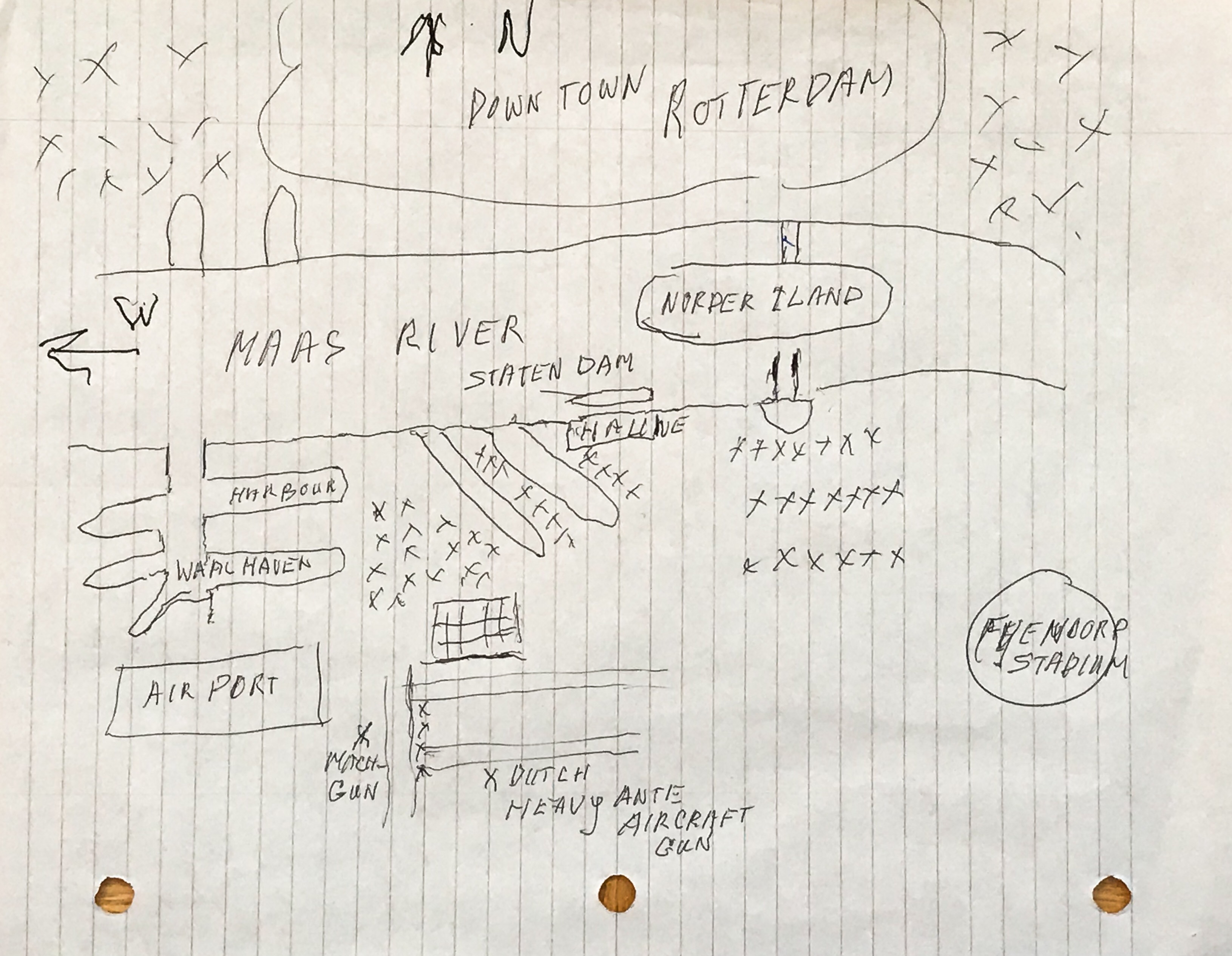

Charlois was on the south side of the Maas River, right next to the Waalhaven dockyards. The city centre lay on the north side, across two bridges linked by an island to the northeast known as Noordereiland.

“Here one morning in May, I’m waking up because there are low-flying aircraft over our roof and I hear shooting,” recalls Verhulst, now 87. “I crawl out of my bed and I see empty shell casings bouncing in front of my eyes on the sidewalk.

“My parents were still asleep. So I went in to see them and I said: ‘Dad, is this the war?’”

His voice rises and his eyes widen as he relives the experience 78 years later at his longtime home in the foothills outside Turner Valley, Alta., a stark contrast to the flatlands of his native Netherlands.

“I guess so, my son,” his father replied.

The Fokker G-1 fighter cruiser with its eight nose-mounted machine guns was a much-feared opponent despite the fact it was slower than newer Luftwaffe fighters like the Me-109. Eight G-1s from the Dutch 3rd Squadron operating from Waalhaven scored 13 confirmed and another three probable kills against two air-combat losses.

“Well, I’ll tell you,” said Verhulst, “in one week’s time, I learned an awful lot about what war was like.”

He watched as German Messerschmitts and Dutch Fokker G-1s fought overhead while Junkers and Dornier bombers hit the nearby military airport. Ten or 11 of the Dutch fighter aircraft had managed to take off. An anti-aircraft gun was firing at the bombers from just a kilometre or so away.

“Then a German plane came in and bombed that artillery site and you could see the pieces flying all over the place. That was the end of that.”

He watched spellbound as a machine-gun crew hidden away in a nearby orchard shot the tail off a German plane and it plummeted in pieces to the ground. “Nobody escaped out of there.”

The following day, he watched again as German aircraft dropped an entire airborne division on the airport, and the fear set in.

“It was unbelievable. This was a morning with a clear blue sky. And all of a sudden the whole sky was white with parachutes—just beside us there. They were close to us. That was scary, especially after they took the airport and they started to come through the fields toward us.

A German Messerschmitt in 1940. This fighter plane was the backbone of the German Luftwaffe. [Wikimedia]

Dutch artillery on the north side of the river was firing over the Charlois rooftops at the advancing Germans, the shells buzzing as they went.

Dutch police and soldiers mounted a defence, stalling the advance for half a day until they ran out of ammunition and surrendered or died in the neighbourhoods around Verhulst’s home.

Their house had become a refuge as relatives moved in from more vulnerable parts of the city.

“A couple of aunts were there and an uncle. There were mattresses lying through the hallways.

“The other uncle was at the frontlines. My mother’s sister was always sitting in the corner crying, afraid for her husband.”

Aerial view of Rotterdam, Netherlands, showing the Koninginnebrug Bridge and Willemsbrug Bridge in 1929. [Wikimedia]

“The fight really started at the bridges,” he said. “First it was police who tried to stop them. Then some of the marines made it to the far bridge.

“There were only 12 of them and they held it for a day. One of them was killed and the rest were able to go back across the bridge to the other side.”

Some Germans made it across and took up positions in the 10-storey Witte Huis, or white house, near the north shore. Built in 1898, it was Europe’s first highrise—and would be one of the few heritage buildings in Rotterdam to survive the war.

The marines managed to oust them but the defence couldn’t last.

British pilot Wilf Burnett flew over the ruins of Rotterdam the day after it was bombed on May 14, 1940. “You can smell the city burning from 6,000 feet,” he said. “I realized then only too well that the phoney war was over and that this was for real.” [Wikimedia]

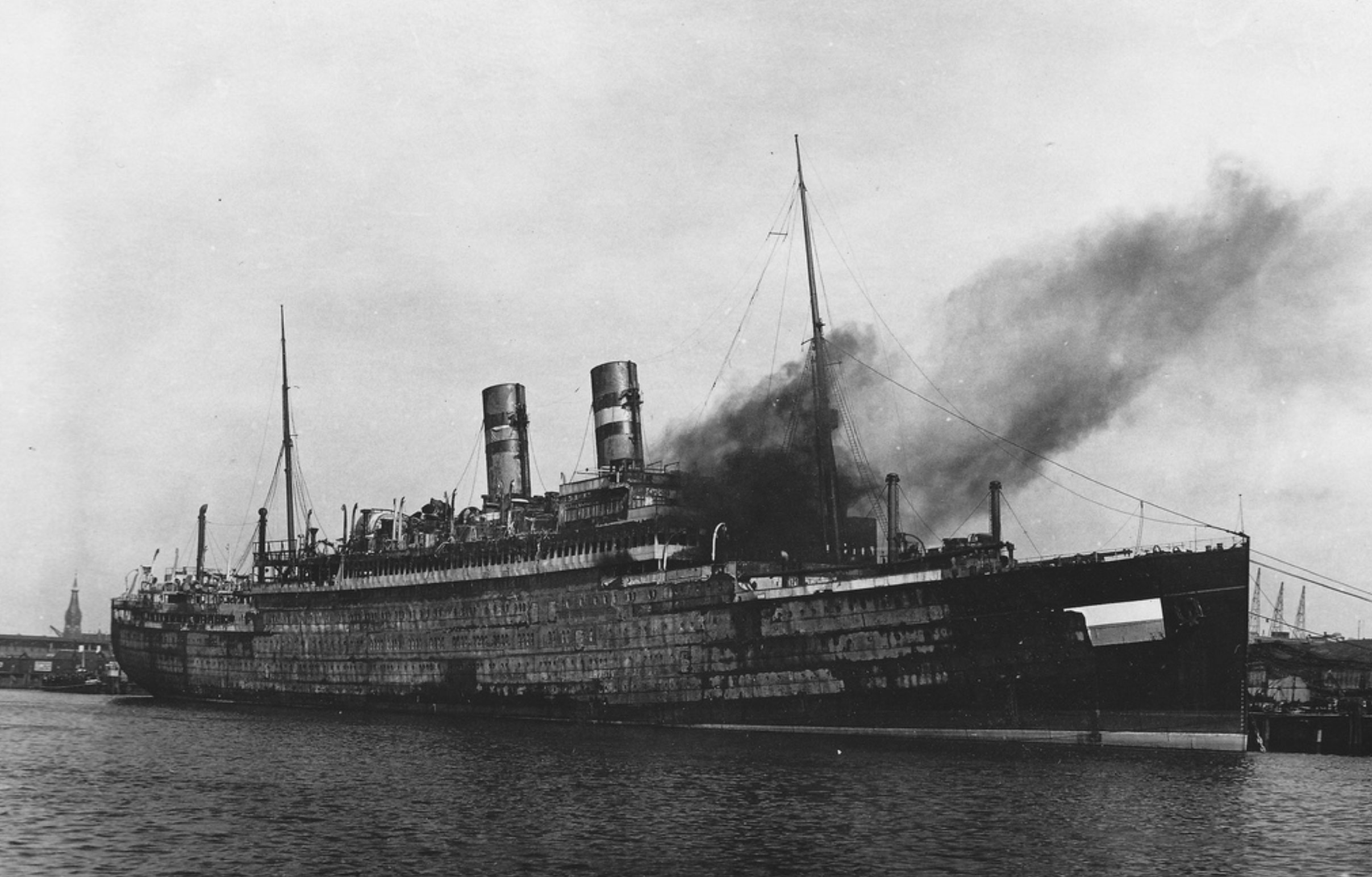

The Germans set up machine-gun posts aboard the Holland America liner SS Statendam. This was the third Statendam operated by Holland America. The second had served as a troopship in the First World War before it was sunk by two German U-boats off Scotland’s west coast in July 1918.

Hoping to avoid mines and more torpedoes, the cruise line had withdrawn its ships from service at the outbreak of the Second World War. Statendam had been laid up from service on the Rotterdam-New York run since September 1939. She and two other liners were damaged beyond repair during the Rotterdam fighting.

Circumstances took a turn on the fifth day. A ceasefire had been declared but the Luftwaffe bombed anyway, destroying virtually the entire historic city centre, killing nearly 900 people and rendering 85,000 homeless.Verhulst said the Germans were angered by the resistance in Rotterdam.

“They levelled the whole inner city—the whole downtown area and a part of the east of Rotterdam,” he said. “We could see it was burning on the other side of the river. There were some terrific fires.”

Ashes and still-smouldering paper from office buildings rained down on Verhulst’s neighbourhood.

His uncle’s family—a father, mother and two children—lived at the epicenter of the bombardment, fleeing as buildings literally collapsed around them and bricks and shrapnel flew past them. They eventually made it to Verhulst’s house.

Verhulst’s hand-drawn map (TOP) of his neighbourhood from recollection. A satellite image (ABOVE) of present-day Rotterdam. [Stephen J. Thorne; Google Maps]

They described how collaborators had shot at the marines from a rooftop. The marines, Verhulst said, went in, captured them and threw them off the building.

“There was a water shortage because a lot of the main lines had been severed. There was a swimming pool and the houses around it were using the water in it.”

Some female cousins survived a direct hit on their home by taking shelter under a stairwell, while two men in the same house were blown from a doorway into the street. At a nearby prison, guards at that moment were opening the cell doors and telling the inmates to “get the hell out of there.”

“So [the inmates] come running around the corner where these two men are still crawling out from the street and starting to dig for the girls under the bricks. Some of those prisoners stopped right there. You have to imagine: this is in the middle of a bombardment; they could easily have been hit doing this.

“But a bunch of them helped dig the girls out. They found them under the stairwell and they were not hurt.”

Rotterdam’s city centre after the bombing. The heavily damaged St. Lawrence church was restored in 1952-68. [Wikimedia]

Thus began the occupation of Holland. It would last the duration of the war, ending in 1945 when Canadian, British and American troops drove out the Germans.

Ernie Verhulst sheds a tear as he recalls the five years he and his family endured under Nazi occupation in Rotterdam.[Stephen J. Thorne/Legion Magazine]

—

This is the first of two stories on Ernie Verhulst’s childhood in occupied Holland.

Advertisement