Lieutenant-Colonel Pat Stogran, commanding the 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (3 PPCLI) Battle Group, had assembled his troops for a final briefing prior to Canada’s first-ever helicopter-borne assault.

Some 80 Taliban and al-Qaida fighters were believed to be awaiting them on a mountain near the Pakistan border where I was to land with eight reconnaissance troops the next morning. Recce: first in; last out. The best place for a reporter.

The colonel introduced me and told the assembled men and women in green that I would be accompanying them and reporting on the operation for Canadians back home. He assured them that, beyond any issues of operational security that might arise, not he nor anyone else would be interfering with my job.

“So don’t screw up,” he cautioned them, adding that I would be a constant presence for the foreseeable future.

It was the best endorsement, and most reassuring gesture I could have imagined. Earning the co-operation of the commanding officer—and his troops—were my No. 1 concerns going into the assignment.

I had been in-theatre a month and had been living in a rented house in Kandahar with a fixer, two Mujahedeen guards, a cook we called Baba and a sweeper (my fixer’s cousin, a quiet guy who appeared to smoke hash all day. I had no idea what he actually did—sweep the insidious Afghan dust—until I got my first invoice).

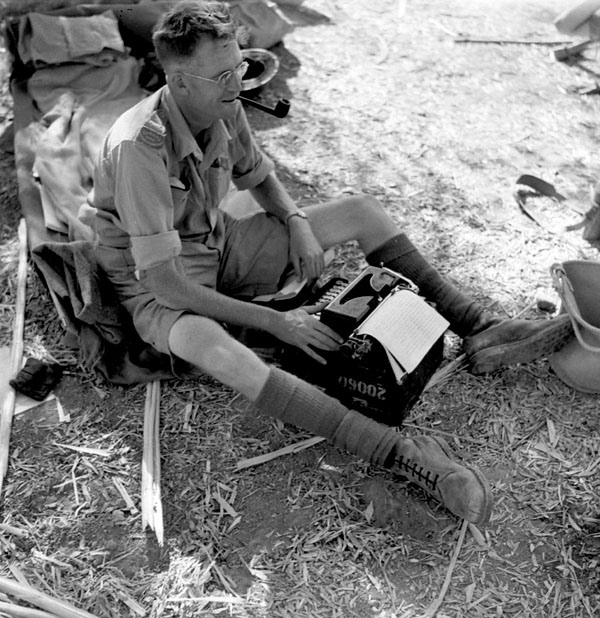

I had been spending my days on patrols with Canadian and American troops, returning to town in the evenings to write and edit images.

Living in a walled compound in Kandahar at the time was interesting, to say the least. My well-connected fixer twice invited Taliban warlords to lunch, yielding some compelling copy, though I wasn’t aware they were Taliban and that my fixer had been paying a regular security fee until some time later.

I never had any doubt on any operation that Canadian soldiers would defend me to the death.

The comforts and other advantages of my setup in Kandahar notwithstanding, I needed to keep my ear to the ground if I wanted to jump onto any last-minute military operations.

So, I eventually took up residence in a small tent on the coalition base at the airport south of Kandahar. I spent weekends when I could at the house working, schmoozing with my Afghan staff and eating rice and kabobs instead of the precooked rations we were fed on-base. A concerned soldier handed me a GPS device and had me globally position the place so they knew where I was if the shit hit the fan.

There was no formal military “embedding” program at the time and reporters were few and far between. Those who did show up would drop in for a week or so and leave, not exactly establishing much depth or rapport with the people they were covering.

I was in-country for about a year during three trips to Afghanistan, in one stretch spending eight-and-a-half months out of 12 there. I always had my own fixer and driver, and I formed strong bonds with many of the soldiers I covered—bonds that last to this day.

At the outset of that five-day mountain op, called Harpoon, one of the recce troops offered me a weapon, saying I should be prepared to defend myself if we were overrun. I declined, telling him reporters don’t carry weapons, to which he shrugged his shoulders and said there would be plenty available should the need arise.

I never had any doubt on any operation that Canadian soldiers would defend me to the death the same as they would one of their own, and they would certainly never leave me behind.

Back home, embedding would become a subject of discussion and debate among journalists and news organizations. The Americans had introduced a program with the invasion of Iraq whereby reporters and photographers would be assigned to specific units for the duration.

While the Canadian military attempted a similar program in Afghanistan, it was never as restrictive nor extensive as the U.S. version. For one thing, there simply weren’t enough Canadian reporters or news organizations involved to necessitate the kind of parameters that the Americans placed on theirs.

Nevertheless, some pundits back home—whose faces I never did see in the combat zone—took issue with the fact reporters generally were living on base and availing themselves of military amenities, as if these “perks” would somehow sway our reporting—to what end, I had no idea, and I’m not sure they did either.

I was sending a second when the military police arrived.

We were there to tell the story as best we could. It wasn’t a city council meeting (I’ve never covered one). It wasn’t point, counterpoint. Rare Taliban statements were taken with a grain of salt. Everything you reported, you did so carefully, keeping in mind that people’s lives—Canadian lives—were at stake.

Any negative reporting largely had to do with government-military tensions; equipment shortcomings; how decisions, or lack of them, in Ottawa affected troops on the ground. Later, after my time, the handling of prisoners of war became an issue, particularly after the Americans, to whom our troops were handing them over, were shown to be torturing and mistreating PoWs.

For me, the priority was the fighting soldier, what they did and what they had to say—not the public affairs officers; not the brass; not the politicians back home.

That there was an enemy was clear. That the coalition cause was just was beyond doubt. And I can write with firsthand experience that Canadian troops were doing their jobs with courage and conviction.

A generation into the digital age, the enemy had the technology to see what you wrote before your editors did. And though I was using a CP-issued satellite system, not the military’s, coalition intelligence officers, too, saw everything I transmitted the moment I sent it to Toronto. They could quote you the exact time an embargoed story went out—and did.

I was kicked off the base three times for supposed violations of operational security, none of which stuck.

The most serious of these incidents wasn’t a matter of “opsec” at all. It involved Canadian medics sent to retrieve the bodies of four American combat engineers killed by a booby-trapped stash of enemy ordnance.

I had been tipped off that they had been dispatched, so I was on the tarmac shooting the medics carrying an obviously full body bag off a helicopter when a hand grabbed me by the shoulder and hauled me off. I was told to sit while the public affairs officer fetched a military lawyer. I waited, then got up, went to my tent and transmitted the picture. I was sending a second when the military police arrived.

The Americans were hyper-sensitive to depictions of their dead. Photographs of body bags helped end American involvement in Vietnam and here, three decades later, the sting was still palpable. No American KIA but for the occasional flag-draped coffin had been depicted in the American media at that point.

A plane-load would appear later. But now the U.S. commander in Kandahar banished me for good. I packed my things and left. Some 24 hours later, after four Canadians were killed in a “friendly-fire” incident involving an American F-16, I was back—encouraged by Colonel Stogran to “keep a low profile for a little while.”

The picture, by the way, appeared on Page 3 of the U.S. military newspaper Stars and Stripes the next day.

Accredited press representatives were therefore to be treated as “valued colleagues with a most important mission to discharge.”

So-called independence of the press, or media, during wartime has been at issue for as long as reporters have covered war. It’s a fallacy.

During the Second World War, correspondents covering operations wore military uniforms, were given the honorary rank of captain, and every word of their copy was scrutinized, often by layers of censors.

The Canadian Press had a cozy relationship with the military of the day. For much of the war, the country’s national newswire service was granted exclusive access.

Its future general manager, Gillis Purcell, actually left his job in Toronto to join the army as a public relations officer in England, only to return to CP some 19 months later minus more than half his left leg, severed above the knee after he was hit by a chute-less supply canister air-dropped during an exercise.

Purcell had initially been dispatched by the wire service to accompany the first Canadian contingent overseas and, among other onerous responsibilities, negotiate a workable system of press censorship with military authorities.

In doing so, he forged a strong working relationship with the Canadian commander of the day, Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton, which ultimately led to Purcell’s enlistment and a position on McNaughton’s staff.

“McNaughton’s goals and Purcell’s overlapped to a remarkable extent,” Professor Gene Allen of Toronto Metropolitan University’s journalism school wrote in his book Making National News: A History of Canadian Press.

“The Canadian commander was determined that the contribution of Canadian forces to the Allied war effort should be adequately recognized, not lost sight of as part of the larger, British-led war effort.”

The military issued its press regulations in May 1941 based on the premise that the “people of Canada have a right to be kept informed…. Military authorities fully appreciate the importance of this task.”

Accredited press representatives were therefore to be treated as “valued colleagues with a most important mission to discharge. They will be fully trusted, treated with complete frankness and given every proper facility for their work.

“The sole restriction on their writings will be that they shall not contain information of value to the enemy.”

That “fully trusted” part, unfortunately, did not always work both ways. Ross Munro’s world-beating, first-person account of the disastrous Aug. 19, 1942, raid on the French port at Dieppe, spellbinding as it was, was ultimately compromised by censors and the fact the military withheld true casualty figures for a month.

Munro was later quoted as calling the delay one of the war’s “most flagrant abuses of censorship regulations.” In another interview, he suggested that the Dieppe Raid was the only time he felt he was “really cheating the public at home.”

“There was nothing very cheerful about the goddamn war.”

Allen reports that censorship had been stepped up after the fall of France and at start of the Battle of Britain in 1940. At the battle’s zenith, on Aug. 15, 1940, reports of air raids on London suburbs were held up for nine hours.

Purcell told CP’s board that while those reports languished in the hands of British censors, “German propaganda multiplied the damage by a factor of 10.”

The North American press had nothing to counter the German claims, Allen wrote. Censorship decisions subsequently started coming faster.

Still, in April 1942 the superintendent of CP’s London bureau had recorded 60 major instances of censorship over six months, with delays ranging from 38 minutes to seven hours. Nine stories were stopped altogether.

Yet Purcell would say that, on balance, “most Canadian war correspondents will agree that the accurate story finally came out but that for various reasons the public was not given an accurate picture of any action at the time it happened.”

Charles Lynch, a Canadian who covered the European campaign for the British-based wire service Reuters, famously concluded that the press “were a propaganda arm of our governments.”

“At the start,” said Lynch, “the censors enforced that, but by the end we were our own censors. We were cheerleaders.”

CP’s Bill Stewart, who had landed in Normandy on D-Day and covered the war through northwest Europe, took exception, saying Lynch fell for this cheerleader idea “and shouldn’t have.”

“There was nothing very cheerful about the goddamn war,” he told Allen in an interview. “There’s this madman over there that you can hear on the radio. And he is walking in here, and he is going in there, and he is kicking the hell out of the British in the desert, and he’s knocking them out of Norway and he is taking over Czechoslovakia and Austria and all this.

“You see, I either wanted to go overseas as a war correspondent or go in the air force,” he said. “I had three brothers in the service and a sister, you know.

“So you weren’t on the Germans’ side, that’s for sure. You wouldn’t want to write anything that would help the Germans.

“There was a lot of heroism and you wrote about it. You were writing from one side of the issue. Were you a cheerleader, or weren’t you a cheerleader? I don’t think you were a cheerleader. I think you were reporting what was going on, on your side.”

War is a state of absolutes, life and death the starkest among them. Degrees of censorship, unfortunately, are a necessary evil in war—so long as restrictions are not absolute, and not abused.

Advertisement