It seemed an assignment more suited to a cub reporter, not the intrepid journalist who would become the national news service’s most celebrated war correspondent.

But then, this was The Canadian Press, for which no story was too small or too big, and there he was, Ross Munro, a man for all seasons, asking troops how they liked the first edition of The Canadian Press News, a weekly newsletter for Canadian servicemen and women overseas.

It was May 3, 1942, and the placeline read “Somewhere in England.” The ill-fated Dieppe Raid, on which Munro cemented his reputation as the country’s premiere war reporter, was still three months away. Sicily, Italy and Normandy would follow.

On this day, however, he was writing what newspaper journalists would come to know as a “puff piece,” celebrating CP’s latest contribution to the war effort.

Soldiers at 1 Corps HQ, Munro reported, were enthusiastically peering “over one another’s shoulders” to read fresh news from home in a preview of the four-page tabloid, 30,000 copies of which were to be distributed to soldiers, sailors and air force personnel with their rations the following day.

“The first few hundred copies reaching the army and corps headquarters were grabbed by servicemen ranging from private to general,” wrote Munro. “In canteens and messhalls they elbowed one another for a look.

“Praise was unanimous.”

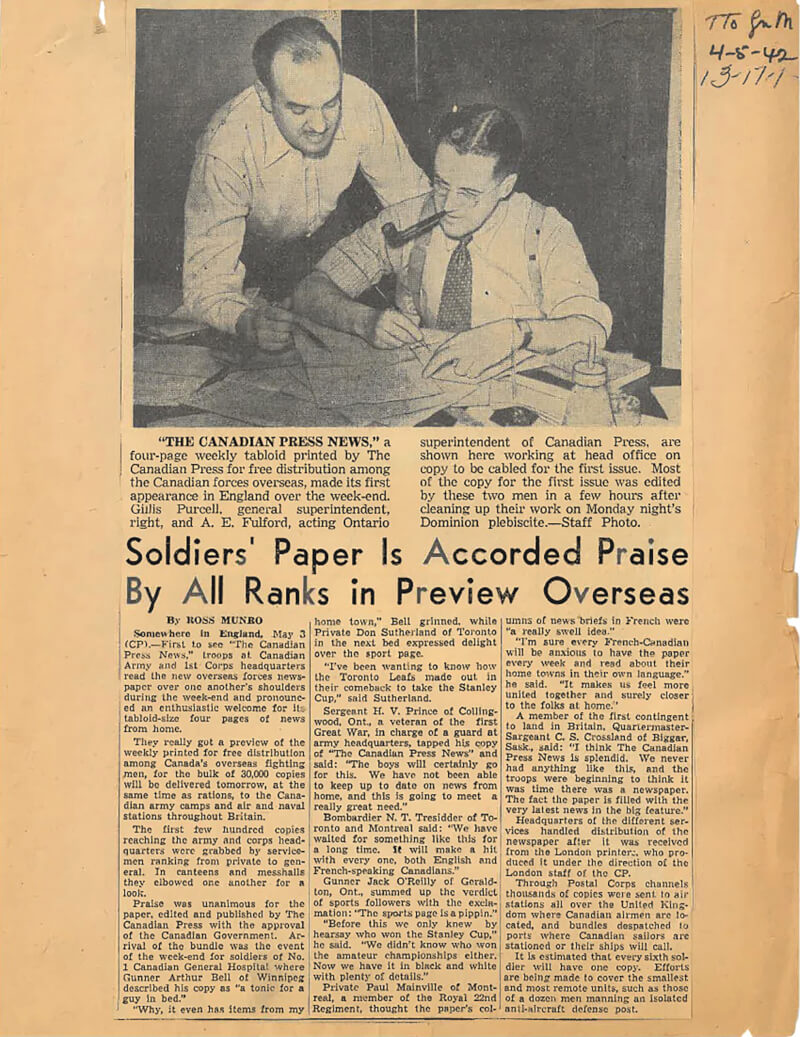

Munro’s account is topped by a picture of A.E. Fulford and Gillis Purcell putting the first edition of The Canadian Press News together in the wee hours of April 27, 1942 after the national plebiscite on compulsory military service.

[CP files]

True to CP’s reputation as a deadline-driven news wholesaler, the pair put the whole thing together in a few hours that Monday night into the early hours of Tuesday morning. It would be transmitted, printed in London and delivered to the troops across England the following weekend.

CP had been delivering special batches of broadcast copy, called The Canadian Press Newsletter, to the CBC for 15-minute broadcasts to the Canadian forces overseas since at least 1940. It would also provide the navy with news reports via the air force.

Widespread use of the internet was still half a century away; television wasn’t popularized until the 1950s; the expense and availability of transatlantic telephone calls was prohibitive for most; and there was precious little time or access for servicemen to keep up on events back home by radio. Periodic letters were a primary source of news.

Copies would be printed enough for one in six soldiers.

The paper included French-language columns, making soldiers “feel more united together and surely closer to the folks back home,” said Royal 22nd Régiment (Vandoos) Private Paul Mainville of Montreal.

“Arrival of the bundle was the event of the week-end for soldiers of No. 1 Canadian General Hospital where Gunner Arthur Bell of Winnipeg described his copy as ‘a tonic for a guy in bed,’” Munro reported.

“Why, it even has items from my hometown,” Bell gushed, while others described the tabloid as “swell,” “splendid,” “a hit.”

Copies would be printed enough for one in six soldiers, reaching what were then some of the Canadian military’s smallest and most remote units along with air stations across England and ports where Canadian sailors were stationed or ships would stop.

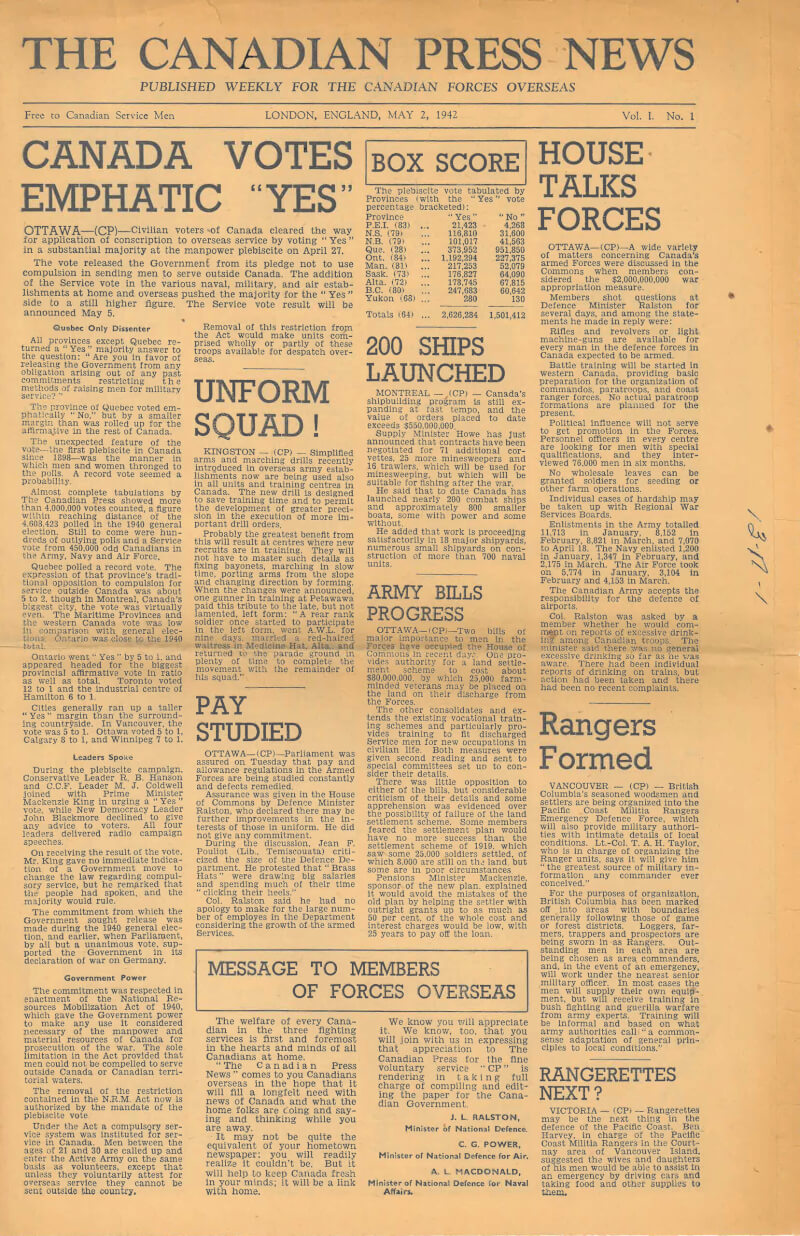

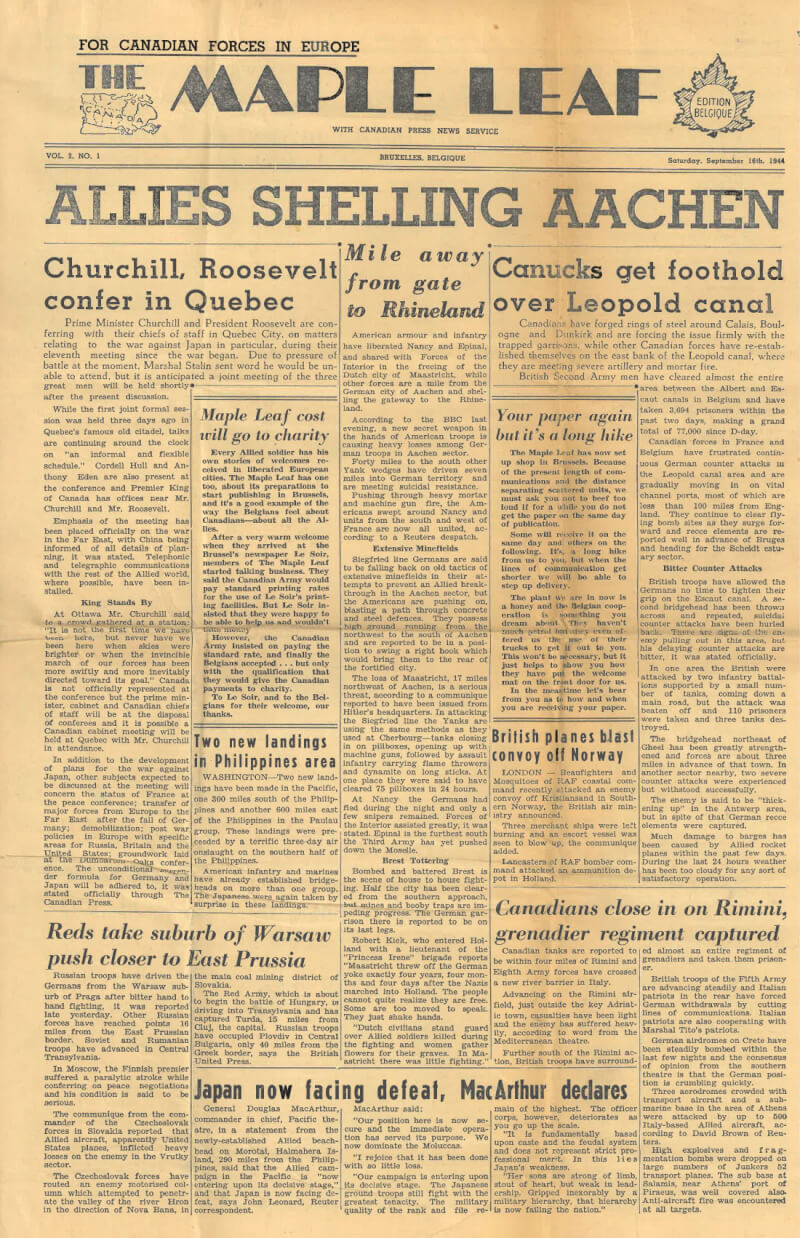

The conscription plebiscite headlined that first edition of The Canadian Press News, declaring “CANADA VOTES EMPHATIC YES” (65.62 per cent, it turned out) on the contentious issue of conscription after the Conservative Opposition pressed Mackenzie King’s Liberal government to reverse its pledge not to impose the measure on Canadians.

The plebiscite on mandatory military service headed the first edition of The Canadian Press News, published in England on May 2, 1942. [CP files]

It was Canada’s first plebiscite since 1898, and it brought out unprecedented numbers of voters, reopening old wounds between French and English Canada in the process.

“Almost complete tabulations by The Canadian Press showed more than 4,000,000 votes counted, a figure within reaching distance of the 4,603,423 polled in the 1940 general election,” said the report. “Still to come were hundreds of outlying polls and a Service vote from 450,000 odd Canadians in the Army, Navy and Air Force.”

In the end, 4,638,847 votes were cast, a 71.34 per cent turnout; 4,488,520 of them were good ballots.

“Quebec polled a record vote,” CP reported. “The expression of that province’s traditional opposition to compulsion for service outside Canada was about 5 to 2, though in Montreal, Canada’s biggest city, the vote was virtually even.”

The relationship between CP and the military was such that Purcell convinced the army to give up one of its Italian campaign assets.

Topping the back-page sports section was the Toronto Maple Leafs rally from three games down to defeat the Detroit Red Wings 4-3 in the best-of-seven Stanley Cup final. The 3-1 game was played before what was then a record Canadian crowd of 16,218 at Maple Leaf Gardens. It was Toronto’s first Cup since 1932.

(The Leafs, who haven’t won a Cup since 1967, are currently averaging 18,819 fans per regular-season game, or 99.8 per cent of capacity—the 11th biggest draw and, at US$2.8 billion in 2023, the highest valued franchise in the 32-team NHL.)

Inside, the tabloid carried a full page of news briefs—one-paragraph summaries of coast-to-coast happenings back home, including the hiring of Victoria’s first woman letter carrier, Florence Bachard; the volunteer enlistment of seven Shaw brothers from Elmsdale, P.E.I.; and the death of Anne of Green Gables author Lucy Maud Montgomery in Toronto.

In Arthur Bell’s Winnipeg, William Gambey caught a man triggering a false alarm.

“Gambey applied for the $10 reward promised on the fire box, but the City Council found there was no by-law providing for payment,” said the item. “However, they gave Gambey $10 anyway, and instructed the city solicitor to draft a new by-law.”

The tabloid was, indeed, well-received. But as the Allied campaigns in Italy and Normandy took hold and Canadian troops left the British Isles for points east, the logistics of providing the country’s far-flung fighters with a printed newspaper were prohibitive to the perennially cash-conscious wire service.

Thus, The Maple Leaf, an army-produced newspaper “with Canadian Press News Service,” was born. The first Italy edition was printed in Naples and distributed on Jan. 14, 1944. By early February, the tabloid was publishing daily with a circulation of more than 10,000 throughout the Mediterranean theatre of operations.

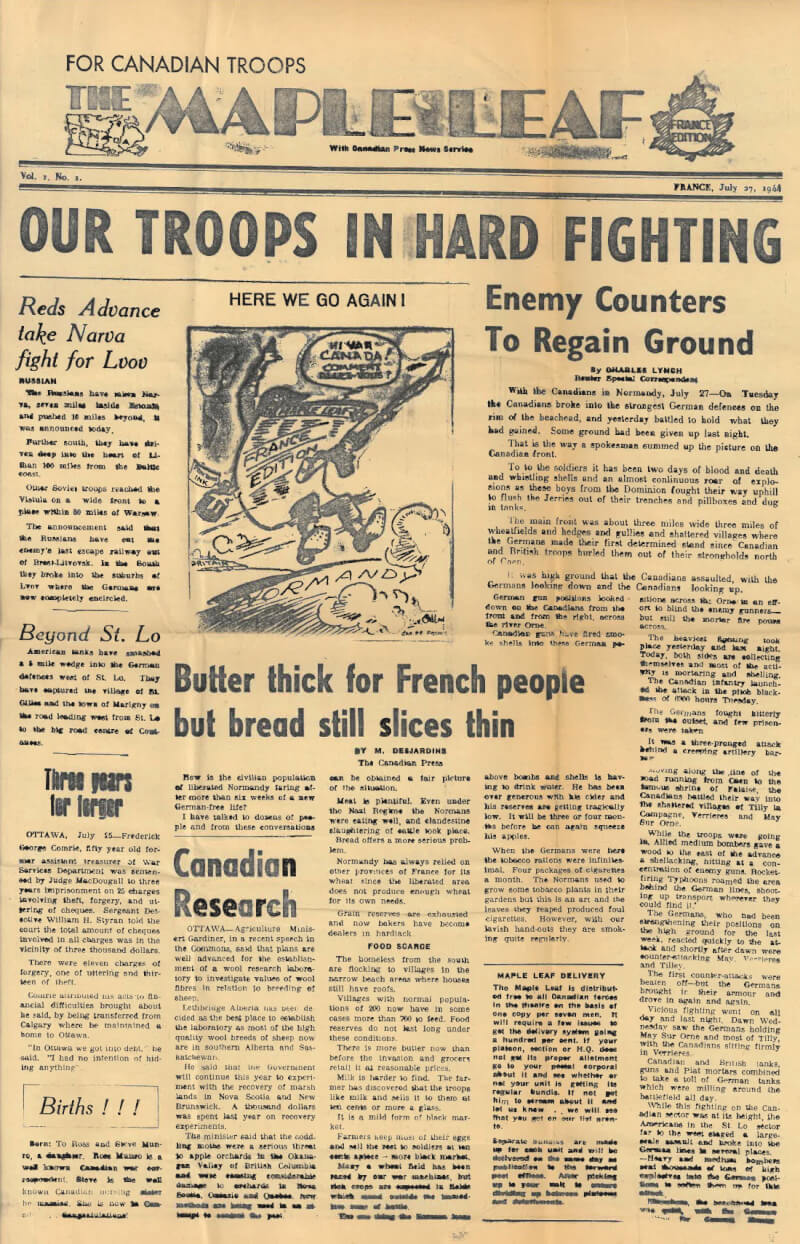

The first France edition of The Maple Leaf was produced in a heavily damaged printing shop during fighting in Caen, France, and distributed on July 27, 1944.[CP files]

The relationship between CP and the military was such that Purcell convinced the army to give up one of its Italian campaign assets, a conducting officer and writer by the name of Bill Boss, a multilingual Renaissance man who would go on to become one of the wire service’s most storied correspondents.

The first issues of a new France edition of The Maple Leaf would be printed under fire out of a ramshackle printing house in embattled Caen seven weeks after D-Day.

“The Canadian newspapers and CP will give us a hand in sending over Canadian news and comic strips, etc.,” said an editorial in the debut issue, published July 27, 1944.

They needed all the help they could get. The city’s electrical facilities were destroyed and shrapnel had ripped through press cylinders, Linotype machines and other equipment in the La Presse Caennaise building where they worked.

“The day we got into CAEN, les bosches persisted in chucking shells and shrapnel into our joint,” wrote the editors. “One day we woke up to find our editorial office missing.”

Labour strikes, racial strife “or other news which would give the Germans a propaganda weapon” were verboten.

On the front page, “OUR TROOPS IN HARD FIGHTING” headed a gripping account by Reuters correspondent Charles Lynch of Canadian gains at the inland edges of the Normandy beachhead.

“To the soldiers it has been two days of blood and death and whistling shells and an almost continuous roar of explosions as these boys from the Dominion fought their way uphill to flush the Jerries out of their trenches and pillboxes and dug in tanks,” wrote Lynch, one of the war’s great Canadian correspondents.

“The main front was three miles wide, three miles of wheatfields and hedges and gullies and shattered villages where the Germans made their first determined stand since Canadian and British troops hurled them out of their strongholds north of Caen.”

Inside the oversized, four-page tabloid, CP’s Bill Stewart, a seasoned reporter and veteran of the D-Day landings, recounted Le Régiment de la Chaudière’s execution of “one of the most spectacular Canadian exploits of the campaign,” the capture of Carpiquet and its airport.

Stewart described how the Chaudières, supported by Sherman tanks, tank destroyers and flame-throwers, vanquished the enemy defences, including trenches, machine-gun nests and concrete casements with walls two metres thick and interior steel bulkheads.

“Flame throwers helped to overcome these strong points which had been virtually immune to the artillery bombardment preceding the attack,” he wrote. “They were hard to capture because their various compartments could be sealed off individually by closing the steel doors between one and another.

“In an early German counter attack, one of the German panthers was set on fire and three more were knocked out later. The Germans had some forty tanks around the airfield and also sent in infantry.”

Production of Italy and France editions of The Maple Leaf was later merged and moved to liberated Brussels.

[CP files]

“We don’t know who won the final,” it declared, “but if Vivian has any more spare time we could give her a few other ideas to keep her busy.”

On the other side of Stewart’s piece is an item about the formation of a Women’s Auxiliary Police Corps in London “to be trained in new methods of dealing with girls who are ‘soldier-mad.’”

“The female morality squads will be trained to investigate the causes of laxness—the glamour of uniforms, drink, lack of parental control in war time, and excess spending money….Equipped with this knowledge the policewoman will be better able to handle girls who are in moral danger, says the Home Office.”

The France-based newspaper would soon merge with the Italy edition and be published out of liberated Brussels. A short-lived London edition of The Maple Leaf, for homebound servicepeople, would come after the war in Europe ended.

The paper continued off and on over the subsequent years and still exists in digital form.

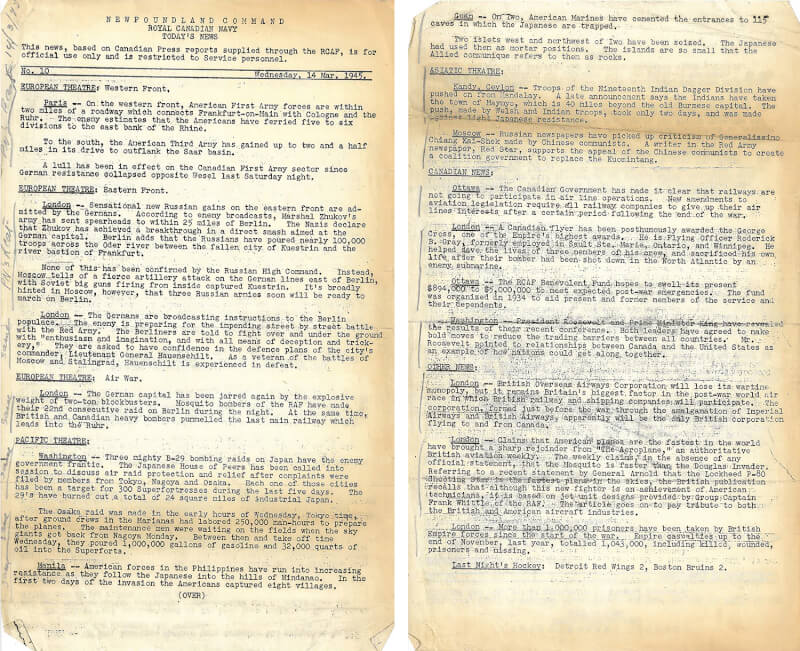

The Canadian Press also provided news and sports to military units and the Red Cross for distribution to Allied prisoners of war held in German and Italian camps. An Aug. 18, 1944, job memo outlined the special considerations demanded of the Friday morning PoW reports.“The bulletins are checked by German censors in Geneva and must be watched closely for anything that would be considered offensive by the enemy,” said the memo. “They must contain no propaganda matter or contentious questions, nothing which would detract from German prestige and no war news.

“Factual political news, such as announcements of elections and their results, may be sent. News of political appointments and bare statements of the programs of various political parties may be used if edited carefully. Omit references to subjects or parties about which the Germans are particularly touchy, such as the communists or other anti-Nazi organizations.”

Local news was fine provided it conformed to censorship rules. Labour strikes, racial strife “or other news which would give the Germans a propaganda weapon” were verboten. It instructed that prisoners should be advised of anything affecting them directly, such as pay changes, gratuities, promotions and deaths.

A March 14, 1945, edition of news for the Royal Canadian Navy, distributed by the air force. [CP files]

If the testimonies of many Canadian PoWs were any indication, the Red Cross kits they were supposed to receive were pretty picked over by the time they got them—if, indeed, they got them at all.

CP’s London bureau oversaw a formidable stable of journalists through the Second World War. Colourful and reliable, the award-winning Boss would go on to travel the world and report on all of Canada’s major battles of the Korean War, the only reporter from any news organization to do so.

Formed in 1917, The Canadian Press was at the time a not-for-profit co-operative owned by Canada’s daily newspapers, whose annual dues varied according to circulation. Its first big story was the Halifax Explosion and it would forge a reputation as the country’s independent national news service. It was bought out and turned into a for-profit enterprise by three media firms in 2010.

Advertisement